Brexit Remembered

14 April 2020 – Steven Bishop

At 11:00 p.m. on Friday, January 31, 2020, the United Kingdom formally left the European Union (EU). After three and a half years of national debate and division since the Referendum on British membership in the EU, the first chapter of “Brexit” concluded. As the end of January approached, talk in the national and local media turned to how the country would commemorate the moment the clocks turned eleven. Should London’s iconic “bong” of Big Ben be restored? Should notorious Leave campaigner Nigel Farage be knighted? Would there be celebratory street parties or vigils to mourn the UK’s departure from the EU?

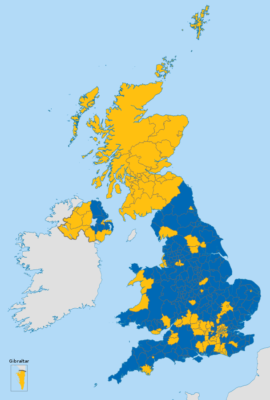

EU Referendum results of June 23, 2016. Yellow indicates a majority “Remain” constituency, and blue indicates a majority “Leave” constituency Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

These questions are fundamental to a broader debate about the relationship between commemoration and public history. What forms will this commemoration take on, if any? Who will decide what aspects of the UK’s departure from the EU to remember and which parts to forget? Some of the answers to these questions were answered at the end of January, but will its commemoration change over time in response to events outside its control?

Prime Minister David Cameron’s referendum on the UK’s membership in the EU on June 23, 2016, concluded a complex fifty-year history between Britain and the European project. A two-thirds majority of British people supported the UK joining the European Economic Community (the EU’s forerunner) in 1975, but the French president Charles de Gaulle believed the British people were inherently wary of the European project. Through 2010, Britain maintained a conflicted relationship with the EU, with prime ministers like Margaret Thatcher suspicious of ever-increasing political ties between the member states as early as the 1980s. Relations improved under subsequent leaders John Major and Tony Blair in the 1990s, but the UK resisted joining the euro (the common currency among many EU member states), and Nigel Farage’s UK Independence Party (UKIP) emerged on Britain’s political landscape, advocating Britain’s departure from the EU.

Despite this, the nation awoke utterly shocked on June 24, 2016, to the news that 52% of the British public had voted to leave the European Union. Parties of all political stripes vowed to uphold the result of the referendum, but deep division ensued for almost three years after the process of departing the EU began. As Parliament grew more indecisive about how the UK should leave the EU (if at all), it took Boris Johnson’s storming victory in the December 2019 general election for Britain to finally “get Brexit done” on January 31, 2020.

How then was Brexit commemorated on January 31, 2020? As the United Kingdom is made of four constituent parts, it may be helpful to break this down by nation. England and Wales were two nations whose populace voted in the majority to leave the European Union. Its commemoration in England was centered around whether Big Ben would chime at the official moment the UK departed the EU at 11 p.m. London’s iconic clock tower has been under renovation since 2017. The prime minister and many members of Parliament argued that the bell should chime for such a historic moment in the nation’s history, noting that it had done so for Remembrance Sunday and New Year’s Eve. Others argued that the estimated £500,000 cost of doing so was unjustifiable. In the end, Big Ben did not chime. Instead, an image of it alongside the Union Jack was projected on 10 Downing Street (the prime minister’s residence), with a sound recording played. The media supported another form of commemoration: giving Nigel Farage the title of “Sir” by granting him a knighthood. Farage, formerly of UKIP and now the leader of the Brexit Party, has been arguably the UK’s most prominent (and divisive) campaigner against Britain’s membership in the European Union. This question elicited the polarized views of commentators and radio listeners up and down the country, but as of yet, he has not made the Queen’s honours list.

Three years of national division followed the British public’s decision to leave the European Union in the 2016 referendum. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons.

In both England and Wales, however, the most ubiquitous question was how everyday people would commemorate an event which had polarized the nation for over three years. Thousands gathered in Parliament Square for a Brexit celebration party awash with Union Jacks and St George’s crosses. One gathering of formerly Labour-supporting, pro-Leave supporters I know in North Essex decided to have a slightly raucous party, only for their Remain-voting neighbor to complain not only about the noise, but about them celebrating Brexit at all. However, the largely pro-Leave political commentary magazine The Spectator had warned “Leavers” to not “rub people’s noses in it” in their celebrations, and the media thus showed scenes across England and Wales of either low-key celebrations in pubs, not too dissimilar from any other Friday night, or quiet candle-lit vigils held by mourners of the country’s independence from Europe.

In Scotland and Northern Ireland, nations that voted in their majority to remain in the European Union, public commemoration was similarly divided. Alongside celebrations were displays of defiance to Brexit Day. In contrast to Downing Street in London, the colors of the European Union flag were projected on two government buildings in Edinburgh and mournful vigils were held across the city of Glasgow. More significantly, Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon commemorated Brexit Day by issuing renewed calls for a second referendum on Scottish independence from the UK, whereby if successful, Scotland would apply to re-join the EU as a sovereign nation. Protests by anti-Brexit groups occurred in towns across Northern Ireland, the part of the United Kingdom perhaps most affected by Brexit due to its land border with EU member state, the Republic of Ireland. Some even suggested the idea of a united Ireland, a remarkably consequential call considering the violent and turbulent history of the matter of Irish sovereignty.

Does this give us indicators of how Britain will commemorate Brexit in the future? This may largely be contingent on the great unknown of how Britain’s future unfolds outside of the European Union. As Raphael Samuel argued, “memory is historically conditioned, changing colour and shape according to the emergencies of the moment.” (Samuel, Theatres of Memory, xxiii) If the UK prospers economically and politically as a sovereign state whilst the EU encounters further dilemmas of controlling immigration across open borders, bailing out economically struggling nations (e.g. Greece) and the rise of anti-EU parties in other member states, then Brexit may be heralded annually on January 31 as an overwhelming success. If the opposite happens and the EU blossoms whilst Britain struggles going it alone, then January 31 could be a day to forget or be encountered with anger, regret and “I told you so’s.” Additionally, if Britain leaving the EU triggers the disintegration of the United Kingdom with Scotland and possibly Northern Ireland going their separate ways, commemoration of Brexit could become even more problematic. And the external, entirely unforeseen global outbreak of the coronavirus may have far-reaching impacts on international politics which one cannot begin to predict.

The post-EU future of the United Kingdom will thus determine who the stakeholders will be in remembering Brexit. Will the history books tell of a celebratory emancipation from the EU written by victorious Brexiteers, or, as with the Lost Cause mythology following the U.S. Civil War, will the losers control the retelling, waxing wistfully of a perhaps mythologised glorious by-gone era of UK membership in the European Union? These are just some of the questions the United Kingdom will face in future years when choosing how to remember and commemorate its fractious departure from the European Union.

~Steven Bishop is a part-time PhD student in History at the University of Essex in the United Kingdom. His research focuses on how statues and monuments of controversial historical figures are coming under scrutiny by the media and general public, in particular statues of Confederate veterans in the United States and those of Captain Cook in Australia.