Call-and-respond to my name, Clemson

21 September 2021 – Rhondda Thomas

archives, social media, African American history, campus history, Higher Education, NCPH 2021 awards

Editor’s Note: Call My Name, Clemson: Documenting the Black Experience in an American University by Rhondda Robinson Thomas received an honorable mention for the 2021 NCPH award for best new book about or growing out of public history theory, study, or practice, for either 2020 or 2021.

John C. and Floride Calhoun’s Fort Hill Plantation house is located near the center of Clemson University’s campus. Image credit: Rhondda Thomas

“Why didn’t you mention slavery?” I asked the docent at the end of my tour of US statesman John C. and his wife Floride Calhoun’s Fort Hill Plantation House that sits in the middle of the Clemson University campus. “Because it’s too controversial,” he reluctantly replied.

That exchange in the fall of 2007 propelled me on a quest to discover more about the enslaved persons who had labored on Fort Hill. I soon learned Clemson is indebted to Black people at every pivotal point in its history. The Call My Name Project researches and documents the lives, contributions, and legacies of seven generations of people of African descent—from freedom in Africa to twenty-first century activism—in Clemson history by utilizing the Call-and-Response tradition. Call-and-Response involves a collaborative interchange between a speaker/musician and audience/group to intentionally engage in meaning-making for a community. An enslaved field hand would sing the first line of a work song and others would respond on the chorus. A jazz musician would play the main melody of a song and other members of the combo would respond with a riff on their instrument.

Similarly, we “call” the names of Black people in Clemson history through posts on social media and invite the public to respond with details that help us fill out these stories. We began with Facebook because the platform provides the versatility we desire to publish different types of stories, from a simple photo and caption to longer narratives. We eventually added Instagram to connect more with college students and Twitter to tap into the academic network and others who are interested in public history projects. With the help of social media, Call My Name creates a powerful counter-story that honors and magnifies the experiences of Black Clemson. I’ll examine our methodology through an analysis of two stories we’ve posted on social media: 1) the calling of the name of Mary Cannon that led to the discovery of her marriage and affiliation with a local church, and 2) the calling of the name of Juanita Webb, a Clemson retiree who became a pillar in the local community but is largely omitted from the university’s public history. These stories not only exhibit the effectiveness of the Call-and-Response tradition for public engagement projects, but they also reveal the necessity of exploring and affirming the interconnectivity of campus and local Black community history.

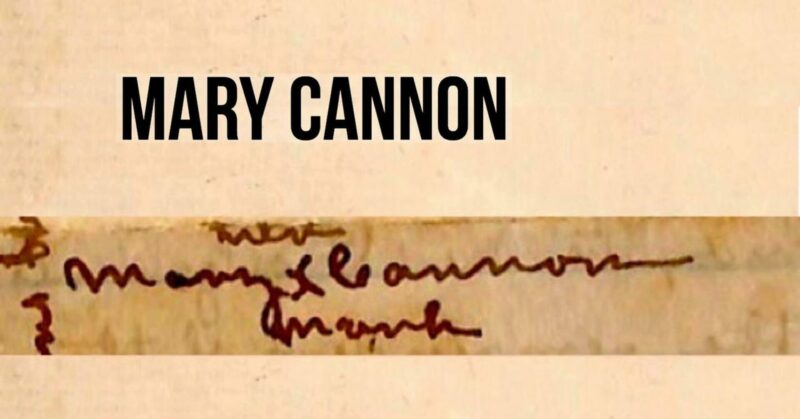

Mary Cannon’s signature with her “X” mark that was included at the end of the labor agreement freed men and women signed to work as sharecroppers for Thomas Green Clemson on the Fort Hill Plantation during 1871. Image credit: Thomas Green Clemson Papers, Clemson University Libraries, Special Collections and Archives, Clemson, SC.

Between October 24, 2016, and May 17, 2021, our research team published nine posts about Mary Cannon on its Facebook page. Mary Cannon was one of 17 freed men and women who signed an agreement with their “X” marks to work for Thomas Green Clemson as a sharecropper on Fort Hill from January 1, 1871, to December 31, 1871. We created posts that included the lists of all of the sharecroppers and those that featured a photo of Cannon’s signature, her first and last name with the X mark in between. As we shared her story, we provided details about what we knew, that she was likely illiterate and may not have understood the expectations conveyed in her labor contract. Occasionally we issued a direct call to our followers: “If you have any further information about Ms. Cannon, please don’t hesitate to reach out to us.”

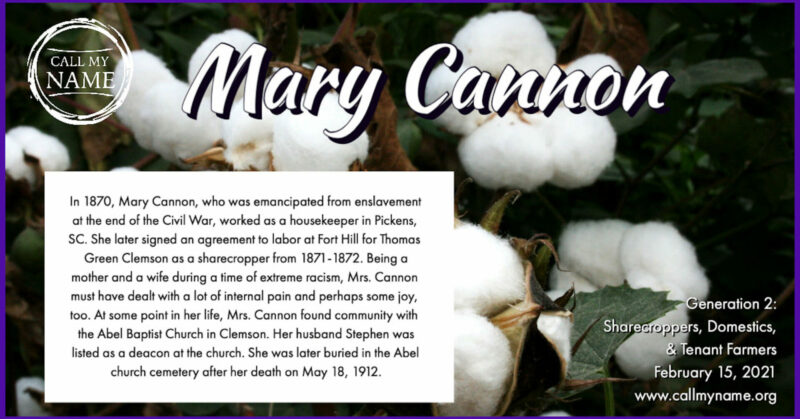

About one and a half years after our first call about Cannon, a follower responded. On April 9, 2018, he wrote, “James ‘Jim’ Cannon son of Stephen Cannon married Bettie Webb. Jim and Bettie are relatives of mine.” Who was Stephen Cannon? Two more years would pass before we learned his identity. Clemson student Michaella Orr became interested in conducting research for Call My Name after a student advisory board for the project was organized in the fall of 2020. I assigned her Mary Cannon’s name, explaining that we hadn’t been able to discover much about her. Soon Orr learned that Cannon was mentioned in the Black Heritage in the Upper Piedmont oral history collection in Clemson’s Special Collection and Archives. She was buried in the local Abel Baptist Church Cemetery. Cemetery records revealed that Mary Cannon was married to Stephen Cannon who had also worked at Fort Hill as a sharecropper the same year she had labored there, and he became a deacon at the Abel Baptist church where they were members. By the time we published a post on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and via email blast about Mary Cannon for our special Black Clemson Heritage edition of Call My Name for Clemson’s Black History Month celebration in February 2021, we could trace her life from enslavement to freedom.

Call My Name Black Clemson Journey Day 16, Black History Month 2021 Edition, February 15, 2021. Image credit: Call My Name: African Americans in Clemson U History, Facebook page.

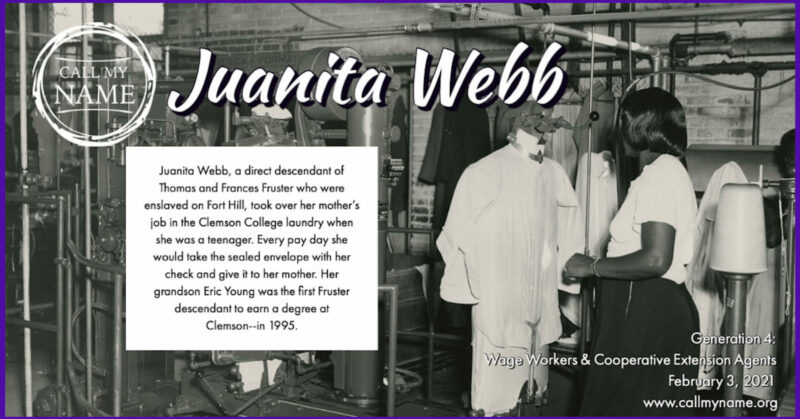

Call-and-Response has also helped us build our audience. For the Call My Name Black Clemson Journey Black History Month 2021 Edition, we also published a post about Juanita Webb that sparked many conversations between family and friends. Webb is a descendant of Thomas and Frannie Fruster who were enslaved on Fort Hill. She and her ancestors have toiled on the land upon which Clemson University was built from the antebellum period to the present. The Webb family first connected with the Call My Name Project through an oral history initiative. In 2016, StoryCorps recorded a series of interviews with African American families who have ties to Clemson. After Webb’s grandson, Eric Young, recorded an interview with his cousin, we discussed how to ensure that his family’s story was more integrated into Clemson history. I soon learned that Webb had worked in the Clemson College laundry, taking over a job that her mother could no longer do after becoming ill. Webb and her family had also come to Clemson for the institution’s first “History in Plain Sight” day in 2018, sharing stories and songs with program visitors.

Call My Name Black Clemson Journey Day 4, Black History Month 2021 Edition, February 3, 2021. Image credit: Call My Name: African Americans in Clemson U History, Facebook page.

Call My Name introduced our followers to Webb, tracing her family story from Fort Hill to sites all over the nation and world and including photographs that documented that journey from enslavement to freedom. The post was shared 96 times, reached 9,033 people, and elicited 29 comments—from relatives, church family members, neighbors, and friends all raving about sweet Juanita Webb with the amazing singing voice. Her grandson later informed me that their family members and friends called each other and responded to the post—and to the Call My Name Project.

Call My Name evokes the collaborative and improvisatory Call-and-Response tradition in African American culture that nurtures collective meaning-making as the names of Black people in Clemson history are called on social media and through other mediums, including books, journal articles, brochures, and websites. Our audiences respond and in effect become part of the research team, helping us to recover and share the stories of those whose narratives are at the center of Clemson University’s public history. The documenting of Black Clemson history that spans more than three centuries and includes thousands of stories requires time and patience. The continued possibility of new responses to our calls, both from the public and in the archives, sustains the momentum of Call My Name.

~Rhondda Robinson Thomas is the Calhoun Lemon Professor of Literature and Call My Name Project Faculty Director, Clemson University, Clemson, SC

My mother is the great granddaughter of Jonas Fruster who was enslaved on the Calhoun plantation. We would like for her to connect with others