Interpreting climate change through human stories at coastal national park sites

02 January 2017 – Jackie Gonzales

Editor’s note: This is the third of a series of blog posts commissioned by The Public Historian on the topic of history and the interpretation of climate change in the national parks, extending the conversation on history in the national parks during this centennial year begun in its November 2016 issue. Read other posts in the series.

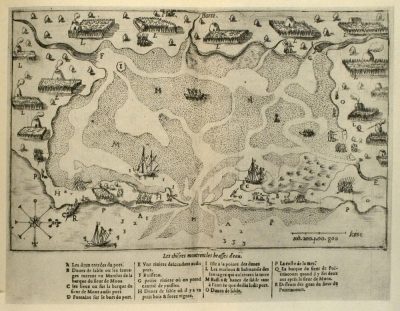

Samuel de Champlain’s 1605 map of Malle Barre (present day Nauset Marsh). Photo credit: National Park Service.

For an interpreter at Cape Cod National Seashore, talking about climate change is easy. It’s everywhere you look. Canoeing with visitors through the same marsh in which Samuel de Champlain once dropped anchor sparks an easy connection–how could even the most talented navigator steer a French frigate into a marsh? The interpreter guides the visitor, explains that shorelines at the Cape have been receding since the last ice age at a fairly steady pace, and that Champlain’s Mallebarre was a harbor some four hundred feet out in the Atlantic from today’s Nauset Marsh. This steady shoreline recession is the same reason that Wampanoag settlements are found on the beach after major winter storm events.

Stairway at Nauset Light Beach, Eastham, Massachusetts, following a winter storm in 2010. Photo credit: National Park Service

While the Atlantic has been stripping sand from the Cape’s eastern shore since the last ice age, the rate of erosion has increased exponentially with the onset of human-made climate change. Increasingly frequent and increasingly intense storms erode and redeposit sand more quickly than the gradual rate with which the Cape Cod landmass has morphed since the last ice age. The climate went from changing at a glacial pace, where settlements had years between significant storm events to recoup, to destructive storm events occurring nearly every year. Staircases down to beaches, once replaced every five to ten years, are now destroyed and rebuilt yearly. Climate change and human stories are so intricately intertwined at Cape Cod that it is choosing which of so many to tell–not creating the links–that is difficult. Most national parks have a different problem.

In Imperiled Promise, the 2011 report on the state of history in the National Park Service (NPS), chair Anne Mitchell Whisnant and her co-authors recommend linking human history to natural history as one way of addressing the divide between history in the NPS and the interpretation of that history to the public. Teaching climate change through human stories is a critical component of this strategy.

Communicating the concept of linkages between climate change and human stories can help the American people understand their place in a changing world. Marcy Rockman, the NPS climate change adaptation coordinator for cultural resources, has developed a framework for addressing climate change in cultural resources management that emphasizes communication. Interpreters at parks with ready visuals, or with an interest in this field, have already begun to successfully interpret these connections. However, ensuring consistency in interpretation remains a systemic problem in the Park Service, where seasonal employees are the face of the agency to much of the public.

Glacial cliffs in Wellfleet, Massachusetts. Photo credit: Jackie M. M. Gonzales

Cape Cod interpreters integrate connections between human history and climate change on a daily basis, but the onus is on the interpreter out in the field to draw these connections to the public. Interpreters point to two-by-fours, bath fixtures, and cement pylons that lie on the beach–a hundred feet below their former residences–to illustrate how winter’s turbulence redeposits cultural resources at a speedy pace in this era of climate change. The houses of the famous are not exempt; park guides can point to Coast Guard Beach, where the same harsh winters that writer Henry Beston captured on the page later destroyed the cottage in which he wrote them. To ensure that interpreters make such connections consistently, the Park Service must include an emphasis on human stories of climate change in training for seasonal rangers. Only then can the Park Service institutionalize the connections between climate change and human history.

Upstream from Cape Cod at Fire Island National Seashore, extensive human building on a fickle shoreline provides a ready visual for facilitating interpretation. The Army Corps of Engineers’ century-long activity on the island and Robert Moses’s decades-long attempt to build a road on Fire Island show both the human material uses that have caused climate change and the effects that climate change has on our built environment and cultural resources. Even the best-engineered coastal embankments face the possibility of destruction in the wake of increasingly intense storms and rising sea levels.

Programming at Fire Island does a relatively good job incorporating these narratives at a small scale. Past programs have included a “Coastal Breach Hike,” in which visitors walk with a coastal scientist to the break that Hurricane Sandy re-created in the barrier island. While programs like this often are led by natural resources scientists interpreting climate change, this discussion of human coastal engineering practices and responses on the island incorporates human stories of coastal control into a natural narrative. These programs should include discussions not only the natural processes of barrier islands, but also of how agencies such as the Army Corps and the National Park Service have shifted their management methods of such events with an eye to more frequent occurrences in a more turbulent climate. National Park Service interpreters could also benefit from a longue durée approach to history–programs about how archaeological sites are threatened by breakages can also address how humans who lived at those sites thousands of years ago dealt with their own slowly warming, post-glacial environment.

The Indiana Dunes, which abuts Gary, Indiana, has been part of the NPS for fifty years. The park’s inholdings include a public port with steel mills and coal-fired power plants, built concurrently to the establishment of the National Lakeshore as a legislative compromise. This highly polluted area, however, is also the birthplace of American ecology. Individuals who launched the study of ecology in the U.S. studied at the dunes, lived in Chicago in buildings made of steel forged in the dunes, used electricity generated in dunal power plants that supplanted the plants of yesteryear, then bemoaned the destruction of the natural environment they had studied. Was there ever a better opening to tell the story of how humans both caused climate change and then tried to fight it?

Present day view of Nauset Marsh from Fort Hill, Eastham, Massachusetts, looking northeast. Photo credit: Jackie M. M. Gonzales

By linking climate change to historical interpretation, the National Park Service isn’t just remaining relevant–the agency is interpreting one of the most important human actions of the last two centuries. As the NPS has started saying in official literature, “Climate change is the heritage of the future.” In this former park ranger’s experience, the public loves to be given the chance to make connections that they never saw coming. Drawing lines that connect seemingly disparate topics can enable history to remain relevant and a new generation of Americans to see their role in creating and addressing climate change. Coasts are an easy place to start, but they are just the beginning. Integrating human stories into narratives of climate change at all Park Service sites isn’t as hard as it sounds; we just need to bring out the stories that are hiding in plain sight.

~ Jackie M. M. Gonzales, PhD, is a former National Park Service interpreter at Cape Cod National Seashore, Manzanar National Historic Site, and Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park. She currently works as a research historian at Historical Research Associates.