Cuban-Americans seek to institutionalize, streamline, their past

02 September 2014 – Michael Bustamante

On July 17, Miami-Dade County Commissioners—several Cuban-Americans among them—approved a controversial plan to construct a Cuban Exile History Museum (CEHM) alongside Biscayne Bay. Few would deny the importance of the Cuban community to Miami’s rise from sleepy getaway to sprawling “gateway to the Americas.” The museum project, however, raises troubling questions about not only the development of seaside green space or the apparent clout of one group in city government but the slippery politics of the past in a changing Miami present.

Located behind American Airlines Arena in the heart of downtown, the proposed site for the CEHM has been the source of public wrangling for some time. After rejecting a proposal to build a soccer stadium on the plot, commissioners gave the exile museum the go-ahead. Conservationists and non-Cuban constituents alike have grumbled at the inside political baseball seemingly favoring the city’s preeminent ethnic voting bloc.No one, though, seems to be debating just what would go into the new building in the first place–the kinds of exhibits it would feature or stories they might tell–let alone how this new institution would sustain its mission over time.

To date, organizers have provided more in the way of architectural plans than administrative vision. In a July 26 column, Nicolás Gutierrez, the spokesman for museum backers, promised an operation of “Smithsonian” caliber without detailing the functional, curatorial, or scholarly resources required. At a time when museum plans around the country are being scaled back, such shortcomings raise red flags–not least because the City of Miami has barred the use of public funds for a project estimated to cost $125 million. Fundraising has a long way to go, and a projected start date for construction has not been announced. Strategies for collaborating with other existing cultural and archival institutions likewise remain undeveloped.

The substantive dimension leaves even more to be desired. According to Gutierrez, planned exhibits include nostalgic “pavilions depicting old Cuba” and the “downfall of the Republic,” as well as features on distinct waves of post-1959 Cuban migration, the Bay of Pigs invasion, and the Cuban Missile Crisis. Museums on the island, of course, feature their own one-sided explanations of such highly debated events. (For revolutionary loyalists, the fall of Batista and the upheaval that followed remain worthy of celebration.) And yet, even allowing for a degree of bias in Miami’s commemorative counterpoint, portraying pre-1959 Cuba as simply “paradise lost” conveniently elides the reasons why virtually all Cubans–including the majority of those who would comprise the Cuban exile community–welcomed the advent of the Revolution at the start.

Equally ahistorical are attempts to portray “the Cuban exile experience” as a quintessential or straightforward “American story,” as Commissioner Esteban “Steve” Bovo put it. Indeed, more than a tale of Latin Horacio Algers, Cuban-American history involves equal parts conflict and consensus. Most people leaving Cuba in the immediate wake of the Revolution envisioned not an American dream but a quick return home. As contending anti-Castro groups negotiated Washington’s fickle Cold War patronage, accusations of duplicity bred an undercurrent of “exile anti-Americanism”–the idea that the United States might sacrifice the Cuban cause on the altar of its own interests.

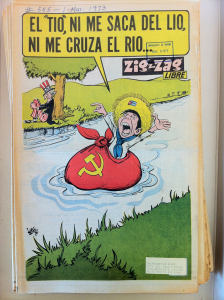

Thus, when Washington moved to ease tensions with the socialist world in the 1970s, allegations of US hypocrisy helped fuel an intensified wave of exile militancy. According to historian María Cristina García, between just 1973 and 1976 more than 100 bombs exploded across the Miami area. In these respects, the transition from Cuban “exile” to “Cuban-American”–from “Tyranny to Freedom,” as the museum’s unifying slogan would have it–hardly proved seamless[1].

Exile Anti-Americanism in the 1970s. Image credit: “Uncle Sam: he won’t get me out of a jam, nor will he put me across the river.” Zig-Zag Libre (Miami, FL), March 1, 1973

Finally, it would be shortsighted to portray all phases of Cuban migration to the United States as merely successive chapters in a cyclical saga of flight. Participants in the Mariel boatlift of 1980, rafters interned at Guantánamo in 1994, and all Cuban émigrés since have brought unique voices, perspectives, and experiences to Miami, at times rubbing up against the political and social mores of their predecessors. The Mariel exodus, for instance, stands out as a moment when not all of Cuban Miami or Miami in general welcomed the predominantly working class, racially suspect newcomers with the “open arms” that Jimmy Carter promised. The rafter (or balsero) crisis, too, blurred the distinction between political and economic motives for migration as never before. Today, young Cuban-Americans’ descriptions of certain places, habits, or people as “reffy”–a play on “refugee,” slang for “off the boat”–suggest that social and economic fissures within the Cuban community persist[2].

Ultimately, the push to inscribe a uniform, fixed reading of Cuban-American history onto the city skyline may stem primarily from contemporary circumstance. Miami is changing as never before, as immigrants from all over Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela especially) bring added diversity and cultural capital to South Florida in their search for economic opportunity. Since the rafter exodus twenty years ago, roughly 500,000 Cubans have arrived in the United States, many of whom do not fully identify with the old guard’s view of Cuba and travel back to the island with frequency[3]. The urgency with which supporters have backed the CEHM, then, may well reflect an aging Cuban-American establishment’s anxiousness to institutionalize a particular historical narrative and legacy before it is too late.

All museums reflect the circumstances of their making. More than passing on established wisdom, however, the most enduring historical displays also encourage us to consider points of view other than our own. Financial sustainability likewise counsels in favor of a more inquisitive, less politicized mandate. Otherwise, sustaining public and philanthropic interest may prove difficult, eventually leaving the city on the hook for a project it had no intention of funding.

No doubt Cubans have left an extraordinary mark on greater Miami’s culture, politics, and economic life. Yet if a building is to be constructed to celebrate that legacy and preserve it for the future, let Miami create a hall for serious inquiry and debate, not a primarily sentimental monument to Little Havana’s “greatest generation.”

~ Michael J. Bustamante is a PhD Candidate in Latin American History at Yale University. His dissertation explores the politics of historical memory among Cubans on and off the island in the wake of the 1959 Revolution.

[1] Maria Cristina Garcia, Havana USA: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959-1994 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 120-146.

[2] Ibid., 46-80; Holly Ackerman and Juan M. Clark, The Cuban Balseros: Voyage of Uncertainty (Miami: Policy Center of the Cuban American National Council, 1995).

[3] Exact statistics are not reported by the federal government, but the number of Cubans becoming legal permanent residents each year is generally taken as a proxy for the number of arrivals. Since 1995, somewhere between 20 and 30,000 Cuban émigrés are thought to have arrived in the United States annually, via a combination of formal and informal means.