Doin’ it for the Gram: How Baltimore’s Chicory Revitalization Project uses Instagram to Engage the Public

26 December 2019 – Sydney Johnson

Editor’s Note: This is the third and final post in a series on the Chicory Revitalization Project. The first post featured the history of the project and the second post considered digitization of the magazine.

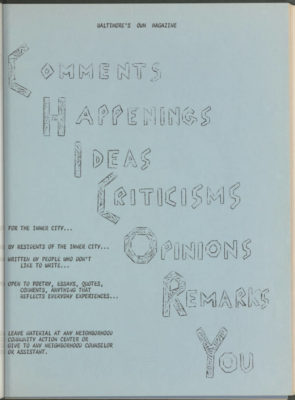

During its nearly twenty-year run, Chicory’s contributors detailed their lives, struggles, and dreams with candor—grasping at fragmented ancestral ties, growing up in the projects, and creating alternate futures for their city. Any number of comparisons could be drawn between the themes detailed in the poetry, prose, and artwork created by East Baltimore’s oft-maligned Black community from 1966-83 and the state of affairs in the same area today. Yet despite the magazine’s timely content, Chicory is an underused resource.

Chicory, Issue 001, December 1966. Back cover. Artist unknown.

In 2017, Dr. Mary Rizzo collaborated with Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library, as well as original Chicory editors, to digitize and host the magazine’s entire corpus on the Digital Maryland platform. However, even with this wonderful advance, we were uncertain if the constituencies that Chicory was originally created by and for were visiting the site. Did our intended audiences know about this digital resource? Were they able to engage with the digitized materials in any meaningful capacity? After thoughtful deliberation, it seemed that an image-driven social media platform like Instagram could be key in helping us bridge the gap between our digitized collection and local communities.

Prior to establishing our social media presence, we had to thoroughly evaluate our online archive. Stakeholders told us that the site itself was not wholly engaging. Basic usability tests revealed that the interface was not visually dynamic, navigation was not intuitive, and its capacity to offer interpretation was minimal. We realized that low utilization of the site was likely not an issue of digital accessibility, but one of user awareness and feasibility. Simply put, digitization was just the first step. We needed a way to facilitate public interaction with Chicory’s offerings while the on-the-ground community-led components of the project developed. Enter Instagram.

As an image-centric social media platform with 500 million daily users, Instagram was the most obvious choice to increase the visibility and impact of Chicory. Whether you’re examining the magazine’s dynamic use of cover art or the structure of the written works themselves, Chicory and visuality go hand in hand. We didn’t have to worry about creating stunning imagery to entice likes, follows, and reposts because Chicory offers a treasure trove of Instagrammable content features. The images featured on the account are high-resolution images gleaned directly from Digital Maryland’s online archive that detail the ephemerality and historicity of the physical magazines they represent. Instagram’s zoom function allows audiences to inspect aspects of a page like discoloration, unintended watermarks, and minute artistic flourishes—details that are typically hard to see without hands-on interaction.

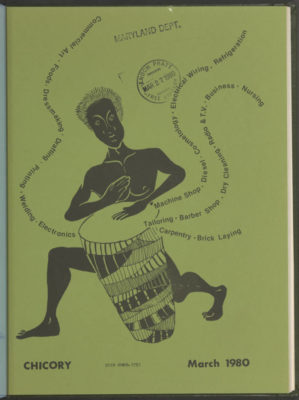

Chicory, Issue 103, March 1980. Image credit: Andre Bradley.

The platform’s multiple image feature, which allows you to post up to ten images or videos in a single post, has proven useful in demonstrating historical continuity. Rather than posting one image or poem, this feature allows us to juxtapose a contemporary news story or community event alongside a related entry from Chicory—thereby plainly highlighting the magazine’s continued relevance. Of course, the featured content would not be as illuminating without captions. We like to think that our posts hook people with captivating imagery and draw them in with interpretive text. To stay aligned with Instagram’s culture of high engagement and moment-based interaction, we try to strike a balance between offering broad context, encouraging publics to engage with open-ended inquiry and close looking, and asking people to share their general reactions to posted content. The caption field, as well as the comments section, provide productive space for conversation, reflection, and connection.[1]

Chicory’s ethos of “by and for the People” also made Instagram the obvious choice for public engagement. Described as a publication “written by people who don’t like to write,” Chicory is the epitome of democratic literature. That the magazine accepted and printed everything from standard poems to plays, quotes, social commentary, and conversations heard in passing on the street makes Chicory and Instagram an even more obvious pairing.

The content featured on the Chicory Instagram page is not necessarily akin to that of the burgeoning “Instagram poetry” genre. However, the page is used in ways similar to that of Instagram poets in that it allows users to directly access poetry—as both art and historical evidence—and individualize their experience with it. In an early post we asked our followers to choose one of three poems that described life in Baltimore City and respond in three words or less. One follower chose a piece of poetic prose titled “reflections after the paying of the rent” from the May 1967 issue of Chicory. In addition to their three-word response of “Scapegoat the poor,” they also wrote, “makes me feel like we are taught who to blame by the people who are to blame. Reminds me of a time I went to a welfare office in LA and all over the walls were pictures of poor people who ‘stole from the system.’”[2] Instagram is altering the finely manicured landscape of poetry by allowing non-traditional engagement with the art form, and Chicory has planted itself firmly in this fertile loam.

As the Chicory Revitalization Project’s inaugural social media content manager, I knew the importance of developing a flexible yet grounding engagement strategy. Instagram can be utilized in myriad ways, as can Chicory’s resources; therefore, establishing initial parameters to ensure some consistency in tone, voice, and image were key. Although I currently create, curate, and manage all published content, the page is undergirded by a style guide and brand voice that I have designed to grow with the inevitable transitions of the project.

#ChicoryChallenge screen capture.

Through recurrent, weekly, hashtag associated posts our page offers followers consistent ways to engage beyond “likes.” We’ve debuted #FOLLOWFRIDAY, #ArtistSpotlight, and the one that garners the most engagement: #CHICORYCHALLENGE. These “challenges” encourage critical thinking and inspire followers to draw connections between their lives and the experiences shared in Chicory.

The @chicory_baltimore Instagram page requires more development, but our Instagram insights and impressions tell us it is already making an impact. Over the last five months, Instagram has proved essential in expanding the reach of Chicory. The Chicory Revitalization Project has forged partnerships in the Baltimore area, while activating its myriad possibilities as a tool of transformation.

For the project’s next steps, we need to deepen our use of Instagram as a vehicle toward increased coalition building. This could look like creating weekly Instagram Stories—a feature that allows you to post images and video in a slideshow format—that depict behind-the-scenes research and content development for the larger project. This content could then be shared on our page via the “Highlights” section, which would add variety to our page while featuring specific phases or partners of the project. Account takeovers hosted by our collaborators like Writers in Baltimore Schools, DewMore Baltimore, or the Enoch Pratt Free Library are also possible ways of expanding our local reach while increasing our Instagram presence. Slowly but surely, Instagram is assisting us in introducing people to Chicory—a historical resource with potential for contemporary change.

~Sydney Johnson is a historian, curator, and Ph.D. student at Rutgers University-Newark.

[1] A particularly notable engagement occurred in the comments section of a September 23 post that featured cover art from Chicory, issue 035, May 1973. This issue featured works from incarcerated individuals, and we asked our followers their thoughts about the abstract cover art. One follower, @black_abolitionists_newark, wrote, “Powerful image. I like how they are using a woodcut looking technique with figures that almost look like they could be wood sculptures. Moving to see a sculpture behind bars…Powerful.”

[2] Instagram comment. June 25, 2019. https://www.instagram.com/p/BzI_BIQBJnk/.