Editors’ conversation on interpreting immigration, Part 2

26 July 2018 – Adina Langer

Crowd gathered at World Refugee Day Celebration in Clarkston, Georgia, on June 23, 2018. Photo credit: Joseph McBrayer, Coalition of Refugee Aid Associations

Editors’ Note: This is the second part of a two-part editorial conversation on interpreting immigration in public history. Part 1 is available here.

AJL: How can public historians effectively take an intersectional approach to interpreting immigration? How can we bring different audiences and stakeholders together?

WW: Collaboration is essential. Hopefully public historians already have relationships with their local immigrant support organizations, but if not, now is a good time to reach out and make connections. Donating time (and money, if you can) and getting involved in existing activities may be the best thing to do currently, especially as these organizations are likely stretched thin fighting on multiple fronts. Refugee resettlement organizations are facing a particularly acute crisis as the number of admissions has plummeted this year.

ML: This is a really important point! Sometimes people on the front lines don’t have time to serve on our committees. Museums and public history sites can also think about their own resources, and what they can offer to organizations.

WW: Overall, public historians should strive to make their communities welcoming. They can advocate for the value of all immigrants to American society. Immigrants often lack places to gather and share their cultures with one another, so public historians can host community gatherings at their sites. In addition, they can organize cultural events and art installations, bring in immigration law experts to provide counseling sessions, facilitate cross-cultural dialogues, encourage multilingualism in public discourse, and tutor individuals for their citizenship exams. In all of these actions, public historians should be sure to include various groups of people, both immigrants and non-immigrants (when appropriate), from a range of backgrounds.

AJL: I also find myself coming at this question from the perspective of wanting to draw parallels among various struggles for recognition and civil rights. African American history and indigenous histories in this country are (largely) not histories of immigration. Some people worry that there are limited national resources to address new immigrants while long-standing injustices remain un-rectified. Others point out the pitfalls of thinking in a nationally-bounded, zero-sum, competitive fashion. Is it possible to model true inclusion while also advocating for particular vulnerable groups within our larger society?

ML: Mae Ngai’s works helped me make these connections. She discusses how the United States’ history of racism frames immigration policy and how people in the US talk about immigration. And of course, there are numerous books about how various groups (Irish, Italians, and Persians, for example) became situated in America’s racial landscape and contended with how they have been “raced” even as they contended with discrimination against immigrants.

When I worked on the History Unfolded project with my students, one of the really interesting issues that emerged was how alive African American newspapers were to the rise of Nazism in Germany, and fascism more generally. They connected it to Jim Crow. It is helpful to think about why these African American journalists wrote about Nazism and condemned it, while their white counterparts were less consistent in their condemnation of “Hitlerism.”

AJL: Yes! I’ve noticed this in the World War II coverage of the Atlanta Daily World.

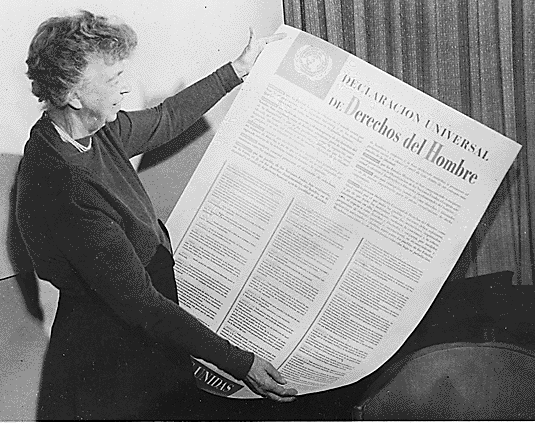

Eleanor Roosevelt with the Spanish version of the United National Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1949. Photo credit: Franklin D. Roosevelt Library via Wikimedia Commons

I find myself thinking a lot about “pride” as a basis for action and positionality in the world. For many, the idea of the United States as a “nation of immigrants” provides justification for advocacy of human rights, openness, and fairness everywhere. There are numerous examples of times we’ve fallen short of these ideals in the past (as well as the present), but do people need a positive story to motivate themselves to action in difficult times? I worry sometimes when I get comments from students in focus groups that “history is depressing.” Sadness tends to make people close themselves instead of opening themselves to new ideas. Should public historians remain steadfast in their faith that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice?”

How does immigration intersect with other “heritage” issues in public history? Is there an effective balance to be struck between nostalgia, inclusion, and constructive criticism?

ML: Ngai’s insights are helpful here, especially in her discussions of how immigration discourse is “raced.” She writes a lot about which immigrants were considered white and therefore eligible for citizenship. For example, the Supreme Court ruled that Bhagat Singh Thind, a migrant from the Punjab was ineligible for citizenship because he was not “white.” Ngai also writes about how the discourse of mixed-status families (in which members may have different immigration or citizenship statuses) echoes the history of mixed-race families, in which relatives have different status based on their skin color, in U.S. history.

WW: It seems to me that the most relevant frame for discussions of immigration is human rights rather than heritage. Although I can see how sites such as Ellis Island and the Tenement Museum can play into powerful cultural forces related to heritage and nostalgia, my sense is that public historians working at these sites strongly resist this pull. Of course we can’t tightly control visitor responses to our sites, nor should we attempt to, but we can encourage visitors to make connections between past and present issues of immigration and, perhaps, to recognize the broader human rights implications of global migrations.

Editors’ note: We invite you to provide your own answers to these questions in the comments section.

~ Adina Langer is the curator of the Museum of History and Holocaust Education at Kennesaw State University. You can follow her on Twitter @artiflection

~ Modupe Labode is an associate professor of history and museum studies and public scholar of African American history and museums at IUPUI. She is a member of the NCPH board of directors.

~ Will Walker is associate professor of history at the Cooperstown Graduate Program, SUNY Oneonta. You can find him on Twitter @willcooperstown.