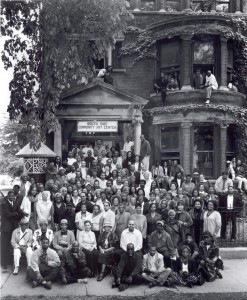

Exhibiting a unique artistic legacy at the South Side Community Art Center

10 June 2015 – Faheem Majeed

art, public engagement, community history, sense of place, interpretation, The Public Historian, historic house museums

Editor’s Note: This post is part of a special online section accompanying issue 37 (2) of The Public Historian, guest edited by Lisa Junkin Lopez, which focuses on the future of historic house museums. The contributions in this section highlight the voices of artists who engage with historic house museums as sites of research, exhibition, and social practice. In this post, Faheem Majeed reflects on his efforts to both animate and protect a remarkable collection in a historic home as the former executive director of the South Side Community Art Center in Chicago.

My entrance into to the South Side Community Art Center wasn’t as a trained professional or as an academic. I came there as a young figurative metal sculptor trying to find support and a community. I walked through the doors in 2003 because I was new to Chicago, and some artists told me that this was the place to go when you didn’t know anyone. To be honest, I didn’t really understand the gravity or importance of the space until some time after I first walked through its worn doors. But like many before me, the center became my home and the foundation for all my future networks and successes.

The center is fascinating on a number of levels. Based in Bronzeville, a predominately black neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side that has remained in a state of flux for many years, the center has an accumulated history that can sometimes be lost in its layers. After a couple of years working as Curator and Executive Director, I determined that the best thing I could do to honor the center’s legacy was to help identify and leverage as many layers as possible.

If These Walls Could Speak

The building dates back to the late 1800s and was built in a Georgian Revival style. When the center came into possession of the space, the board commissioned students from the neighboring college, Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), who were trained in New Bauhaus methodology, to redesign the interior. One of the most fascinating aspects of this renovation is the main gallery, which is lined with sanded and stained knotty pine planks and was designed to record a memory of every artist that hung artwork in the space through the marks of the nail holes. After 75 years of mark making, it has become one of the most beautiful and innovative gallery spaces that I have ever come into contact with. When you are in it, you feel the presence of everyone who came before you.

Art class at South Side Community Art Center, Eldzier Cortor (top left) and Gordon Parks (top right), early 1940s. Photo credit: Jack Delano

The origin of the center was a collaboration between Chicago’s wealthy social elite and a group of young black artists who wanted to attract the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration to Chicago’s South Side and make a home for the numerous visual artists, poets, writers, dancers, and arts enthusiasts. At that time, black artists were limited in their ability to gather, exhibit, and engage around their work, and the center provided a supportive home. Over the years, numerous artists have moved through the space, including Charles White, Gordon Parks, Gwendolyn Brooks, Elizabeth Catlett, Kerry James Marshall, and Theaster Gates. Many of these artists mounted their first exhibitions in the space and took part in caretaking and fundraising for the space.

Once I began volunteering for the organization in 2003, it became clear that it was a close-knit, insular, and familial place. Although the galleries and exhibitions were open to the public, there was an invisible barrier preventing the majority of people walking through the doors from getting too close to the organization. This essentially kept “outsiders” and the “unknown” at bay. This practice came out of a concern by long-time stakeholders that black culture and history would be co-opted and appropriated.

I, however, was welcomed with open arms. Maybe it was because of my studies at a Historically Black University or the rarity of being a black figurative metal sculptor.

Perhaps I reminded the older members of the previous artists that had called the space home. Whatever the reason, I was treated like a long lost son. Over the course of the next four years, I moved through a variety of roles within the organization, finally landing as the Executive Director in 2007. During that time, I realized that the act of being guarded and protective of the institution also prevented sincere interaction, socialization, access to resources, and exposure that the organization–and its artists–needed to thrive. By figuratively opening the doors and cultivating strong partnerships and diverse perspectives and by projecting a more welcoming atmosphere, we encouraged long-time supporters and new friends to became more invested in the success and legacy of the organization.

Collective Clutter

In the 1960s, the founder of the South Side Community Art Center, Margaret Burroughs, sat at the center of the Black Arts Movement. Before she passed in 2010, I had an opportunity to get to know her and better understand her philosophy of the role that her art played in advocating for, and communicating to, the community. A gifted artist, her core belief was that art should be accessible to the masses. She mass-produced her work–in later years using low-quality black-and-white printers–which people then attempted to commodify. Now, placed in numerous black homes above the kitchen table or the family couch, many times there is no understanding of the deeper meaning behind the images. Through repetition, essentially making the work “bigger,” it actually became smaller, lost its focus, and in many ways disappeared from the larger art world.Yet, the center maintains a collection of Burroughs’ artwork along with an amalgamation of artworks accumulated serendipitously over time.

The center’s “collection” is made up of roughly 300 works of art dating back to 1930, and all of the work in the collection was donated, commissioned, or abandoned by an artist that had found their way to the space and eventually moved on. The collection also encompasses the wonderful ephemera that have accumulated in the space. Flyers, Polaroids, cast-away art supplies, and other objects serve as memory markers of the many artists, directors, board members, and visitors who have made their own unique mark on the history of the center. But there are spatial limitations to what can be stored in “the vault.” The ephemera that weren’t necessarily deemed worthy of keeping ended up on a shelf in one of the classrooms. The center had been entrusted with these objects’ safety, pending the slight chance that their owners would return. I often joked that a big part of my job was moving things from one side of the classroom to the other. Regardless of how they came to rest or where they were stored at the center, these objects were markers of events and the passing of time within the space.

In 2012, as part of an exhibition curated by Adelheid Mers at Hyde Park Art Center, I was invited to create an installation as a part of my own art practice. I decided to use this opportunity to show the South Side Community Art Center’s collection to a broader audience. I spent hours in the basement of the center, pulling various objects that lacked voice and “value.” I intentionally selected objects that might point to smaller, un-highlighted moments in the institution’s 70-year history: a flyer from a show in the sixties, a fundraiser hosted by Bill Cosby, oilcans and car parts, printmaking inks, and left over painting supplies from art classes.

When separated, some of the items may be valuable to certain audiences for their individual appeal, but for most of the objects, their appeal is lost in the unbundling…thus limiting their value as a collection. But when placed together, they are all related by their shared history, telling a story about the organization. Simultaneously, an odd juxtaposition began to reveal itself. In one hand, I had Margaret Burroughs, whose contribution to the art community may be considered marginalized because of her approach of mass-producing her work to make it accessible. In the other, I had a pseudo-collection of miscellaneous objects and artwork, which only became valuable when placed together en masse and made accessible to a broader audience.

It is in the act of unbundling–the pulling back of layers and age–where I found that moment when the center became home. Although not apparent when you first approach its worn doors, it is a moment I have attempted to replicate and share so that others can see and realize the value in adding to the layers.

~ Faheem Majeed acted as curator and then Executive Director for the South Side Community Art Center from January 2005 – 2011. He is currently a full-time practicing artist based in Chicago, IL. He can be reached at [email protected].