From #MeToo to systemic cultural change: a public historian’s call to action

08 November 2019 – Chel Rose Miller

#MeToo, advocacy, bystanders, profession, employment, conference, gender/sexuality, ethics, 2019 annual meeting

Image from the workshop “From MeToo to Prevention Bystander Intervention Training” at the NCPH 2019 annual meeting. Image credit: Kelly Schmidt

The #MeToo movement has shed light on the widespread prevalence of sexual assault, harassment, and abuse, including in scholarly and professional communities. The last two years have shown us that the public history community is no exception.

At the 2019 Annual Meeting of NCPH, I co-facilitated a workshop with my colleague, Michelle Carroll (End Rape on Campus), titled “From #MeToo to Prevention: A Bystander Intervention Training for Public History and Museum Professionals.” Bystander intervention is a prevention strategy in which someone intervenes when they see or hear behaviors that could escalate into harassment or violence. This approach helps us address potentially harmful behaviors before sexual violence has occurred in the first place. It also gives everyone in the community a role in preventing harm, including sexual harassment and gender discrimination. Through small group discussion and interactive scenarios, participants learned how to identify sexual violence, how to support survivors who disclose their survivor status, and how to safely intervene as a bystander to prevent sexual violence in their workplaces and communities.

We knew public historians, especially NCPH members, had been talking about sexual harassment and gender discrimination within the field. Between the NCPH Diversity and Inclusion Task Force’s survey and the 2018 Annual Meeting’s “On the Fly” session on sexual harassment and gender discrimination in public history, participants shared experiences that included observing sexist and objectifying comments, being misgendered by colleagues, and witnessing or experiencing explicit sexually inappropriate behavior in the workplace. We expected that our training would attract public historians who have identified sexual violence and gender discrimination in the field as problems and who were looking for ways to address it. What we didn’t expect was that public history would have a virtual “#MeToo moment” during the 2019 NCPH annual meeting.

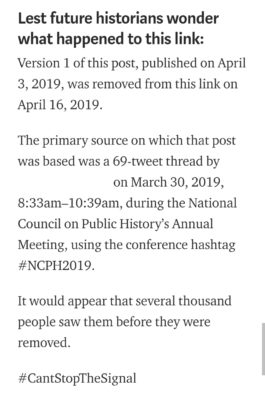

Screenshot of Medium post, originally published April 3, 2019, and redacted on April 16. Personally identifying information has been redacted by the blog post author

Screenshot of Medium post, originally published April 3, 2019, and redacted on April 16. Personally identifying information has been redacted by the blog post author

This particular “#MeToo moment” took the form of a public disclosure of prior sexual harassment and abuse. On the morning of March 30, 2019, a 69-tweet thread in the #NCPH2019 hashtag—and an accompanying Medium post, which has since been redacted—shared the personal account of a public historian’s experiences with sexual harassment and abuse involving a well-known and highly praised public historian they had worked for in the past. The thread reported that this behavior was a pattern of abuse that was talked about among public historians through whisper networks, and that this individual received awards and accolades for their work, despite the harm caused.

The tweet thread raised several questions for me: Is public history work worth praise when the project is led by someone who does harm, no one intervenes, and victims are silenced? How many more unnamed public historians have been silenced or pushed out of the field after experiencing sexual assault, harassment, or abuse? How many more survivors need to come forward before we change our policies and practices to hold people who do harm accountable and support those who have experienced harm?

Our community has systematically failed to ensure that public historians can work free from sexual violence and that public historians who experience harm can safely disclose, receive support, and heal without the threat of retaliation. Moreover, any information we have on sexual violence in the public history community only scratches the surface. These are just reported incidents. It’s not inclusive of stories of harm that have not been told. Survivors may stay silent for many reasons, including fear of not being believed, lack of institutional support, lack of trust in the criminal legal or medical systems, or fear of retaliation that would sabotage their career.

In Trauma Stewardship: An Everyday Guide to Caring for Self While Caring for Others, trauma scholar Laura van Dernoot Lipsky explains that every larger system, or organization, has an obligation to the people who make it work, as well as the people it serves. At the same time, Lipsky continues, each of us plays a role in shaping the organizations and social systems in which we participate. I began reading Trauma Stewardship to help me navigate how bearing witness to trauma can impact people in anti-violence work. I’ve also found that it provides a useful framework for anyone who bears witness to trauma to develop strategies to care for themselves and for their peers.

NCPH—including its staff, Board of Directors, and committee leadership—has certain obligations to us as the professional organization that represents public historians. The NCPH Board of Directors just approved changes to the NCPH Events Code of Conduct, first introduced last year, which applies for attendees at NCPH events, and the Governance Committee is now turning to revisions for the larger NCPH Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct which applies to members at and outside of NCPH meetings, but hasn’t been revised since 2007.

Public history organizations must also be required to implement codes of ethics and professional conduct that include grievance procedures and paths to accountability and healing in order to maintain good standing as NCPH organizational members.

Leadership at museums, public history sites, and academic public history programs—must use their positions of power to implement change in their organizations from the top down. As directors, supervisors, and mentors, it is your duty to introduce policies meant to prevent sexual harassment and gender discrimination. It’s also your duty to prioritize efforts to transform organizational culture into a culture of care and compassion—one that prioritizes support and healing for survivors of harm and accountability for people who do harm.

Public history organizations of all kinds can design and implement policies explicitly stating that sexual harassment and gender discrimination are not allowed. Violating these policies should result in termination and/or removal from the premises. Each state’s workplace discrimination laws provide protection against sexual violence in the workplace, but these laws don’t always include public historians in precarious positions. Organizations that use the labor of consultants, contractors, volunteers, and/or interns must ensure that they are also protected by the policy. In the case of visitors and guests, language in sexual harassment policies should clearly state that visitors/guests are subject to this policy, and organizations should have signage that indicates what is and is not allowed on the premises. Some resources are the model policy created by New York state and changes recommended by the New York State Coalition Against Sexual Assault to make that policy survivor-centered and trauma-informed.

As NCPH members, we have certain obligations to one another as colleagues and peers—when we see sexual harassment or gender-based discrimination occur, we have to act. Here are some actions that public historians can take to support each other and our communities:

-

- Learn how to identify sexual violence. Sexual violence is any sexual act that is perpetrated against someone’s will. This is a term that encompasses a wide range of harmful activities, including a completed nonconsensual sex act (like rape), an attempted nonconsensual sex act or abusive sexual contact (like unwanted touching), or non-contact sexual abuse (like threatened sexual violence, exhibitionism, or verbal sexual/gender-based harassment).

- Form “microcultures of support” or “pods.” Identify who will both encourage you and hold you accountable. Who can you call on when you have experienced harm, when you witness harm, or when you have done harm?

- Know how to identify and intervene in a harmful situation. Attend a bystander intervention training offered by your local rape crisis center or anti-sexual violence organization, or join my next bystander intervention training at the 2020 Annual Meeting in Atlanta.

- Take action if you witness an incident or hear about one. There are different ways to respond, and not everyone can or will be able to safely intervene in the same ways. Some people might directly respond; they take responsibility as the person intervening and confronting a situation directly. Others might use distraction to redirect the focus somewhere else if they witness an escalating situation. The most common strategy is to delegate, or asking a peer or someone in a position of authority to intervene. If necessary, this can include emergency response (for example, law enforcement, EMTs, etc.).

- Know how you will respond when someone tells you that they have experienced some form of sexual violence. Because sexual violence is so widespread, it is likely that someone will disclose to you. Before you find yourself in this situation, familiarize yourself with sexual assault support services in your community—know the name and hotline number of your local rape crisis center, or have the number for the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline, organized by Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN), on hand. Your state coalition against sexual violence can also connect you to your local rape crisis center.

If we do not act, we are complicit in the violence that has pushed countless public historians out of the field. We must now actively work towards eliminating sexual violence from the field.

If survivors of sexual assault, abuse, or harassment in the public history community would like support regarding past or ongoing experiences, they can find help using the National Sexual Assault Telephone Hotline. The Hotline is a referral service that can put you in contact with your local rape crisis center, which has trained advocates on staff who can provide free, confidential support. You can call the Hotline at 1-800- 656-4673, or access RAINN’s online chat service.

~Chel Rose Miller is a public historian based in upstate New York. They are the Communications Director at the New York State Coalition Against Sexual Assault. They tweet as @publichumanist.

Thank you for your article. The Gender Equity in Museums Movement (GEMM) took a first step in ending sexual harassment in the museum workplace this week when it published a pledge stating “We believe everyone on the gender spectrum is a strong and valuable resource for museums and heritage institutions; we all need to play our role in making society a better place, to no longer play the quiet bystander.” The pledge is available now on Change.org, and on the GEMM website.