Hamilton: The Musical: Blacks and the founding fathers

06 April 2016 – Annette Gordon-Reed

race, The Public Historian, theater, TPH 38.1, "Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton" responses

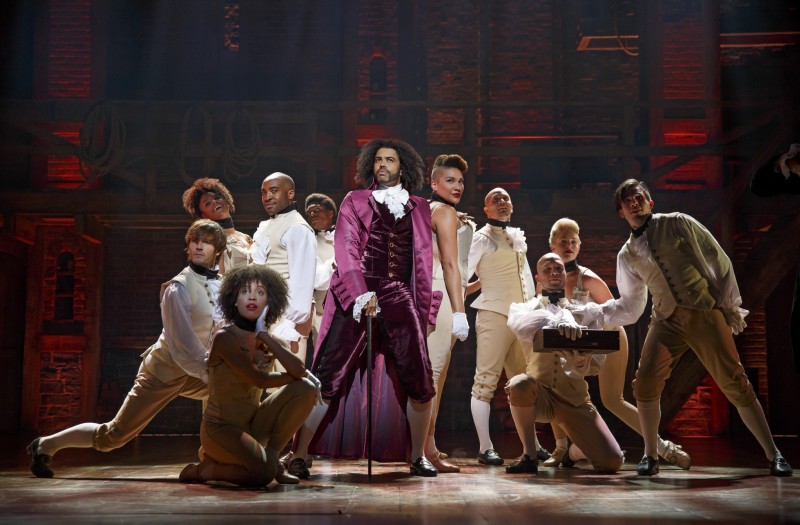

Daveed Diggs as Thomas Jefferson and the ensemble of Hamilton. Photo by Joan Marcus.

This past August, I went with a group of historians to see the much acclaimed, and now Grammy-winning, musical, Hamilton. Our timing was just right. The ticket prices were reasonable (for the Great White Way), costing nowhere near the astronomical sums people pay now. We were not disappointed. Everything that has been said about the ingenuity of the play is correct. The lyrics, the music, the energy and talent of the cast, in the words of one of the play’s songs, “blew us all away.” It was a special thrill to see people about whom I write singing songs with lyrics that included letters that I have read, analyzed, and cited. I bought the cast album as soon as it came out, and I listen to some part of it every day. Not in a million years would I have thought that I would be walking down the street singing along with a song about “The Reynolds Pamphlet.” There is little doubt that Lin-Manuel Miranda is a musical genius and that his creation is a tour de force.

And yet, there are things about Hamilton that give me pause. That is why I am happy to be able to engage with Lyra Monteiro’s bracing analysis of the play in her recent review, “Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past.”

One of the most interesting things about the Hamilton phenomenon is just how little serious criticism the play has received. Indeed, it has played to near universal acclaim from points all along the political spectrum. How could this be? How could a work that so unabashedly celebrates the founding fathers, and has no storyline for black characters, not take some hits from academic historians who have spent the past several decades arguing against unrealistically heroic portrayals of the founders and arguing for including people of color in the story of America’s creation? What, in this age of concerns about inequality and big banks, are we doing going gaga over a play about a man who promoted both?

In different ways, Monteiro and Ishmael Reed, with his hilariously entitled piece “’Hamilton: The Musical’: Black Actors Dress Up Like Slave Traders . . . and It’s Not Halloween,” zero in on the role that race has played in Hamilton’s reception, specifically its use of black actors to play the founding fathers. This casting is one of the things that has garnered the most praise. But Reed is adamant: having black actors portray the founding fathers makes a mockery of the suffering of the blacks whom they enslaved.

But it’s complicated. One could argue that audiences should be allowed to suspend disbelief and let, say, Daveed Diggs (Thomas Jefferson and Lafayette) do what all actors do: step out of their actual identities and pretend to be other people. The difficulty is that this suspension cannot be total. We must notice that the actors are black, or the play’s central conceit does not work. We are asked to be open to their blackness so that the play’s touted message—that the founding era also “belongs” to black people—gets through. At the same time, we are presumably not to be so open to the actors’ blackness that we feel discomfited seeing them dancing around during the sublime “The Schuyler Sisters” proclaiming how “lucky” they were “to be alive” during a time of African chattel slavery.

There is no question that having a black cast insulates the play from criticisms that might otherwise appear. The genius of black music and black performance styles is used to sell a picture of the founding era that has been largely rejected in history books. Viewers (both white and black) can celebrate without discomfort because black people are playing the men who have been, of late, subjected to much criticism. Imagine Hamilton with white actors—there are white rappers, and not all of the songs are rap. Would the rosy view of the founding era grate? Would we notice the failure to portray any black characters, save for a brief reference to Sally Hemings?

This last point takes us to Monteiro’s critique of the casting, which is more detailed and far stronger than Reed’s. I don’t read her as saying that having a black cast is presumptively wrong. The problem is that the use of black actors excuses the failure to portray black historical figures. Viewers don’t notice that there are no “black” characters because the stage is full of black people. She is also right in saying that selling the cast as depicting “Obama’s America” or “America now” does, unwittingly I think, suggest that the revolutionary period was “white.”

Elizabeth (Eliza) Schuyler, portrayed by Phillipa Soo, and Alexander Hamilton, portrayed by Lin-Manuel Miranda. Photo credit: Joan Marcus

Monteiro’s view that the play does not, as some have said, employ color-blind casting is fascinating. Race is not just about skin color. As she correctly observes, the actors sing in particular “racialized musical forms,” with some who “read as white” singing the “‘white’ music of traditional Broadway” and others, who “read” black, singing black musical forms.

Conforming to American gender and racial rules, the “black” Angelica Schuyler is dynamic, aggressive—“fierce” as the young people used to say–while her “white” sister Elizabeth is demure, ladylike, and, evidently, marriage material. Despite being in love with Angelica, Hamilton marries Elizabeth. Now, Miranda had to change some details to get us to the excellent tune “Satisfied.” The real Angelica Schuyler was married by the time Eliza married Alexander. And despite the play’s breaking of casting barriers, the Hamilton family—including wife and son—read as “white,” in the midst of other “black” characters.

Finally, even if there is only one black character in Hamilton, slavery and race do appear, but primarily to establish Hamilton’s “goodness” for modern audiences. He is depicted as an ardent abolitionist, which he was not. The Manumission Society, of which he was a president, was extremely moderate and not at all an abolitionist outfit. He is said to have owned two enslaved people and bought and sold them for others. He was much better than other founders on the question, but almost certainly did not believe that the colonists would “never be free” until people in bondage had the same rights as everyone. The John Laurens character sings those words, but the Hamilton character verbally agrees to them. The audience is able to feel better about the era because there was some antislavery sentiment, and they can supposedly draw a direct line from that to where we are now.

Despite all of this, I love the musical. It is brilliant, and were it not, I confess, I’d probably be less forgiving. It is Miranda’s task to create great art, and he has done that. He is also free, and we want people to be free, to write the play he wanted to write. However, when artists attempt to use art to present history to the public, I think it our duty to use what we know of history and culture to comment on the attempt. Monteiro has done very well on that score, and has given us much food for thought.

~ Annette Gordon-Reed is a professor at Harvard University and co-author with Peter S. Onuf of “Most Blessed of the Patriarchs”: Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of the Imagination, forthcoming in April 2016.

Editor’s note: In “Race-Conscious Casting and the Erasure of the Black Past in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton,” published in The Public Historian (38.1), Lyra Monteiro asks, “Is this the history that we most want black and brown youth to connect with–one in which black lives so clearly do not matter?” This is the last of four posts published by The Public Historian responding to Monteiro’s review. Monteiro will respond in our next post.

Hi Ms. Gordon-Reed, thanks for posting your response.

As for Monteiro’s article, I have a mixed opinion. I both disagree and agree with some of her arguments.

Sorry if it gets long winded; I had a lot of thoughts!

1) I disagree with Monteiro when she says: “The idea that this musical ‘‘looks like America looks now’’ in contrast to ‘‘then,’’ however, is misleading and actively erases the presence and role of black and brown people in Revolutionary America, as well as before and since. America ‘‘then’’ did look like the people in this play, if you looked outside of the halls of government. This has never been a white nation. The idea that the actors who are performing on stage represent newcomers to this country in any way is insulting.”

I don’t think anyone actually thinks that these actors are newcomers to the US. The whole “America then vs America now” statement that Miranda makes is more about positions in power rather than claiming that only white people existed in the 1700s. In “America then” people of color pretty much had no position of power in society whereas we (I’m an Indian-American) do now. I think we can both agree that people of color definitely existed in the 1700s, but sure as hell didn’t have the power to influence how the constitution was drafted (I view the creation of government as something people in power can contribute to. While African Americans definitely played a crucial rule in the war, they did not hold any positon of power). So I have to disagree with Gordon-Reed’s interpretation that “selling the cast as depicting “Obama’s America” or “America now” does, unwittingly I think, suggest that the revolutionary period was “white.””

2) This was not in the original article but in the slate article. It bothered me enough that I wanted to comment on it. Monteiro said, “The female character who sings more Broadway-style ballads [Elizabeth Schuyler, played by Phillipa Soo] is Chinese American, but she definitely reads as white, and I think that is not a coincidence.” I’m sure Ms. Monteiro was well-intentioned but this particular quote struck me and several others as tone deaf. Why is it that the non-black/latino PoC reads as “white”? Is it because her skin is more white? Phillpa is biracial, but so is Daveed Diggs, Chris Jackson, and Jasmine Cephas-Jones. Jasmine’s character (Peggy/Maria) never raps either and has very broadway-esque singing parts. While Odom Jr (Burr) does occasionally rap, his primary singing style is broadway-style songs (“Wait for It” and “The Room Where it Happened”). In “Your Obedient Servant,” the song is very noticable because Hamilton constantly raps and Burr responds in melody. Phillipa, in addition to her lovely ballads, beatboxes in the song “Take a Break.” I realize that I am harping on a very small point. But based on the reactions on twitter and what I personally felt as an Asian-American, words do have power and this was tone deaf in my opinion. While I appreciated this article, Ms. Gordon-Reed, you repeated the exact same problem in this piece. Both Eliza (half-asian Soo) and Phillip (latino Ramos) read “white” to you. And from this assumption, you create an analysis that takes up the next paragraph. I don’t really have anything else to say, but would ask that you try and understand my point of view and why I find your words troubling.

3) Does this musical erase characters of color? I thought about this for hours. I certainly agree with the points that GW’s slaveholding is not mentioned (probably because he is a “good guy”) and that TJ’s views are explicitly derided (to denote him a villain). This is an oversimplification of both men, but I also understand the constraints of writing a musical which needs clear protagonists. So I definitely don’t have a problem with Miranda writing it that way but I think it’s good for audiences to realize that history is more complex than a musical, so it’s great we’re talking about this. I also acknowledge the Cato/Mulligan point in Monteiro’s article. I think this is the best example of a PoC that could have appeared in the musical (since Mulligan was one of his friends). Again, I understand the narrative rationale behind Miranda’s change in terms as the quartet of friends was established early on in the first act.

I agree slavery isn’t the focus of the musical, but it does show up strongly in a few places. E.g. the song Cabinet Battle #1 explores the complete hypocrisy of Virginia being debt-free because they rely on slave labor. John Laurens mentions his abolitionist viewpoint (My Shot and Yorktown). Is slavery the main focus? Certainly not. But I’m also not sure how the musical could’ve incorporated slavery more without completely shifting the narrative from Hamilton’s political conflicts (which I interpreted was the main theme). Maybe it could’ve been done, but it wasn’t.

Interesting fact: Miranda *did* write a third rap battle concerning slavery but had to cut it because the musical was too long and it didn’t make any sense plotwise to fit it in.

But does the musical erase characters of color? I’m going to go with “I’m not sure but leaning on the no side.” Obviously there are no characters of color in the show (exception of Sally Hemmings briefly). Also obviously is that people of color (mainly African Americans) played important roles in the Revolution and were slaves. If the musical was titled “The American Revolution,” I think I might agree with you. But it’s based on the life of Alexander Hamilton, a white founding father whose *primary* conflicts dealt with other white people. I’m not certain if he ever interacted with Cato or had significant interactions/conflicts with other African Americans. So if you want to make a two hour show on his life, slavery and the contributions of black Americans are probably going to be put in the sidelines. But does the constraints of a two hour show trying to pack 50 years actively erase people of color? This is where I go into the “I’m not sure” territory. I stand by the fact that people of color were probably not a source of important conflict/importance in Hamilton’s life. But then could the musical have shown slaves or Black Patriots in the background? With a multiracial cast, this is very difficult to do because how can you tell the Black Patriots apart from white soldiers? I can’t tell you what Miranda should or should not have done. There is an inherent impossibility of casting certain characters as slaves when the cast is multi-racial.

4) Monteiro ends her paper by referencing an interview with Leslie Odom Jr. LOJ talks about how being in this musical has changed his mindset and how he can now “reclaim” a part of history that he didn’t feel accessible to him before the show. Monteiro poses the question of whether PoC should want to reclaim a history which enslaved them and implies that the answer is no. She asks, “Is this the history that we most want black and brown youth to connect with–one in which black lives so clearly do not matter?”

Obviously I cannot (and will not) speak for all PoC, so let me relay my personal experience. I am a first generation immigrant from India who moved here when I was six and grew up in Charlottesville, VA (TJ’s hometown). But even though I was not a citizen at the time, I felt American and considered this place to be my home. Learning about America’s fouding is enough to make any PoC alienated: I would not have been welcome in this special moment of founding. Yet even despite acknowledging the horrible legacy of slavery in the 1700s, I eventually felt connected and “reclaimed” my connection to the special moment of founding. Anyone who has read Machiavelli’s Discourses will understand just what a special moment that founding is. But just because I take pride in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution and want to “reclaim” that piece of American history to my identity doe not mean I ignore the brute realities of that time. The 3/5 amendment will forever stain this nation. If PoC (such as I or LOJ) originally felt alienated by American founding because we did not see ourselves in it, why is “reclaiming” it via Hamilton mean that I am necessarily approving of the other atrocities of that time. Why can’t I have a nuanced approach and admire the legacy of the Federalist Papers on today’s’ judicial cases yet still rebuke George Washington on his slaves? If I feel pride and connected to the founding moment, it’s because I look at the constitutional amendments and countless SCOTUS cases and see how far we’ve come as a nation. And then I look at the inequalities of the present and feel pride that that systems established in 1700s will allow us to further equality in the future. I feel deeply connected to America’s founding even though I am first generation. “Reclaim” is not necessarily a synonom of “wholeheartedly approve.”

5) To Ms. Monteiro and Ms. Gordon-Reed: thanks for your contributions. I disagreed with a lot, but still enjoyed the food for thought. I greatly admire your works and hope to engage you in a conversation.

Apologies for any grammatical errors. I typed this on a ipad.

Adding on to point #2)

Ms. Gordon-Reed writes, “Conforming to American gender and racial rules, the “black” Angelica Schuyler is dynamic, aggressive—“fierce” as the young people used to say–while her “white” sister Elizabeth is demure, ladylike, and, evidently, marriage material.”

Perhaps an important thing to remember is that this is a work of theater and not frozen in history (like a film is). One of the understudies for Eliza is a black woman. I suppose Eliza turns into an aggressive and dynamic (fierce) character when the very talented Alysha Deslorieux is on stage. Now that Hamilton has risen in popularity, the producers are beginning to cast for national tours in Chicago and San Francisco. The ad specifically called for all people of color. It very well may be that the roles switch. Perhaps Angelica will be played be a Hispanic or Asian woman. The characters of Angelica and Eliza are not and should not be set in a particular race.

“And despite the play’s breaking of casting barriers, the Hamilton family—including wife and son—read as “white,” in the midst of other “black” characters.”

Phillip Hamilton (played by Puerto Rican Ramos) raps in both “Take a Break” and “Blow Us All Away.” Applying your logic that black actors perform black muscial forms, he somehow reads as white? I will add that the understudy for Laurens/Phillip is also black.

I think the casting of King George as white is deliberate and significant to his singing style. But I just can’t get past the analysis since it relies on the assumption that non-black PoC automatically “read as white.” Perhaps that says more about the viewer than the casting, because I most certainly did not read either character as white.

I just have too much to say, but this comment will be shorter! 😀 I promise.

I had a twitter convo with someone who said, “Narratively, Hamilton is a 3-legged stool: history, theater, hip hop. You can’t do critique like this with only two legs.” She also added, “The story came about because LMM connected the STORY of Hamilton hip-hop narratives, not because he wanted to tell a historical story with cool music.”

I wonder if this is why I sometimes have differing views from your interpretations. For example, Monteiro in the slate article discusses the dangers of the bootstrap narrative that Hamilton presents. She writes, “This idea that if you’re smart enough, you can write your way out of the projects, kind of a thing? I do think it accounts for why the musical has been so popular among conservative commentators, who fucking love it… It’s a politically dangerous narrative, because it has the tendency to obscure the ways in which so many people are blocked from those kinds of opportunities.”

At first I was inclined to agree with Monteiro’s analysis (I had heard and learned about this idea in several history classes in college), but something niggled at me. That’s when I realized that Hamilton’s bootstrap narrative can be viewed through more than just a historical/political lens of obscuring those without opportunities. The history of hip hop is integral to the work. Hip hop is not just a cool way of presenting music. The history with rappers is omnipresent in the musical. LMM has said that Hamilton is the most hip hop thing that he could imagine. AH “wrote himself out of poverty” just like many hip hop rappers did and found success in the strength of the written word. It was this initial similarity between AH and hip hop that influenced LMM to tell the story via hip hop music. So since I recognized the hip hop background, I viewed the “dangerous bootstrap” ideology completely differently than Monteiro did. From a historical and political lens, advocating the bootstrap narrative may be dangerous in a vacuum but I don’t think you can ignore the influence of the hip hop/90s rappers context on the show. When I think of Hamilton writing himself out poverty, it’s the american dream to some extent but *to me* it’s more the hip hop context that informs me.

An addendum to the bootstrap thing: I think it’s interesting that Hamilton’s ability to write himself out of poverty and *always* speak his mind was also his downfall. In Hurricane, he turns to writing the Reynolds Pamphlets. He sings, “I’ll write my way out… Overwhelm them with honesty.” Here, writing led to a huge sex scandal and a decline in public reputation in politics. The duel between Hamilton and Burr was arranged via letter writing. And again, writing (the thing that got him out of the island) also led to his downfall. So I actually think the bootstraps narrative becomes a little subverted because the thing that caused his success also contributed to his downfall. So there isn’t always a consistent idea that Hamilton’s writing leads to success (which in turn mitigates some of the danger of the bootstrap narrative).

I think the historical/hip hop/political/theater lenses need to be fully integrated to have a thoughtful critique, but this is very difficult to do. After all, who has expertise on all those lenses? It’s far easier to focus on just one. But I wonder if combining the lenses may lead to different interpretations. What do you guys think (I am a complete amateur in scholarly critique and would like to hear your professional opinion)?

I stumbled on this discussion as the Tony’s were playing on TV. I did not see the play, am not a theatre fan, and have seen very little theatre. The debate over using black actors to portray white people from history is really a debate about two separate things: how to portray history and theatre. I think the theatre part is easy to put to bed. It is common in theatre for actors to play people different than themselves. At my local theatre it is fairly common to have a woman play a man (costumed and made up to look male but obviously a woman). It’s not as if they couldn’t have found a man to play the part, but it’s now a thing to do. Less commonly men in drag play women. Young actors play older characters and vice versa. And people of different ethnic or racial heritage play parts that were originally written for white Anglo Saxons. Because of racial sensitivity this has not fully carried over to race blindness in theatre – but, why not? I think the only question here is should a black actor playing a white character wear make-up to look white? Can a white actor play Walter Lee in “A Raisin in the Sun”? Should he do it as a white version or use make up to give him some semblance of looking black? Any of this seems possible. Fundamentally, if it’s well intentioned and well done, it can be art. Is this silly? Well some people think that whites shouldn’t be doing rap music and blacks shouldn’t be performing classical European music, but for the most part we have gotten past that.

As for how Hamilton reflects on US racial history, slavery, etc., we should debate the actual history not the ethnic nature of the characters in a play.

At approximately the same time that the white Founding Fathers were establishing America a group of blacks were establishing their own new nation – Haiti.

Blacks have had relatively few inventions, works of art, and accomplishments anywhere at any time. Hijacking American history is not welcome.

“Blacks have had relatively few inventions, works of art, and accomplishments anywhere at any time.”

Are you completely racist, on massive drugs, or both? Educate yourself, Patrick, because you are CLUELESS.

You sured told them. Let’s be honest…where would sub Saharan Africans be if it wasn’t for the Arabs or Southern Europeans, specifically the Portuguese? They would still be stuck hunting and gathering or involved in subsistence agriculture. While sub Saharan Africans were crossing rivers, Europeans were crossing, and mapping, oceans.

Excellent observations. The main thing, the only thing is that slave holder Hamilton was NOT black so we have revisionist history flung in the face of fact right from the old get go. Not interested. Read Gore Vidal’s outstanding novel, “Burr,” for a real observation of those glossed over times.

I found this via Twitter post. After reading the posts, I am compelled to respond. I took Hamilton @ LMM’s word: to represent America as if it were being established now, in the 21st century. I never questioned—I enjoyed. I, as AG Reed, had listened to the music several months prior to seeing the show in summer of 2016. Now, my take on multi racial casting: I viewed the choice to use this style the answer to a child’s dream. The child? Me. By the time I was in my teens, growing up in a segregated south, I wondered why pigment played such a place in how people were treated and viewed. At the time I was primarily thinking of African Americans. Wasn’t long when that wish included Hispanics. In my 30s I had a strange adventure and was able to live 5 years in SE Asia in a country d whose population included Malaysians, Chinese, and Indians. Upon return to the USA, those shades were added to my wish people of the world would one day “see” people.

As to the political discussion of the day (1700s), I agree with the takes on such. Being an avid theater fan, I do suspend disbelief once those lights go down. I am in the moment. Because this particular show answered my childhood wish, I was elevated to a realm I’ve never visited in life or in drama.

I am a grandmother now, and will be taking my grandchildren to see Hamilton this spring. I don’t know who is more excited! They are listening to the music and have viewed lots of clips on TV and you tube. One of the observations I’ve made is not one (all teens) has mentioned anything regarding the races. Last summer we had backstage passes and they have seen our pictures with Daveed, Phillipa, Chris, Renee, etc. Not a word was said about the pictures of the actors. They have been in and out of NYC for theater since the youngest was in Kindergarten. I’m putting that in so that you can surmise if it’s the exposure to theater which causes that—-or if I am getting my childhood wish and seeing a fabulous show.

This is just plain odd and screams appeasement when none is rightfully due. I am sure a broadway show casting MLK as a white guy would not be acceptable. Not sure why it is okay to cast a black man for this historical role when it was a white man who lived it, unless the apologist director is trying to give future generations a warped sense of reality.

It’s interesting, genetically a white man is within a black man, the recessive genes hidden within the DNA of those darker peoples. While a white man could never comprise or become a black man. Dominant genes not being present. Perhaps it’s within a brown man to play a white man and not vice versa. Based on your reply it would take a few years at a decent uni to comprehend how useless your sentiments are so I thought you should consider that fact instead.

I am not a theater fan but, I can see how in theater anyone can play anything/anyone or Cats would not have happened (I think a female or transsexual MLK would be appropriate). If anyone finds that inappropriate, perhape one should think about how disrespectful others may find other casting choices.

There should be some disclaimers though because the people in this country, under a certain age, do not look at actual history. These people (most people under 30, no matter the color, creed, etc…) are so woefully under-educated that they take theater, opinion and art as fact.

Hamilton was great, but to anyone who should stumble upon Patrick’s uninformed comment stating that “Blacks have had relatively few inventions, works of art, and accomplishments anywhere at any time”, please educate yourselves. Not only does he lop all Black peoples under one umbrella as if we are all one people no matter where we are one this globe, his unfounded claims are reminiscent of old klan campaigns & pseudoscience which promoted false claims of white people being superior over Black peoples.

In this century, we are all fortunate to carry palm-sized computers in our pockets which provide an unlimited wealth of knowledge… Plus, public libraries STILL exist. We are no longer living in the dark ages where one simply had no means to verify information, & we should have already grown past the attempts to discredit entire races of people, for the sake the protecting the myth of white superiority now. The world as we know it has seen brilliance stemming from all races of people, especially Black peoples who have walked this earth since the dawn of man. It’s highly ignorant to assume out of all these past centuries, that Black peoples never created new ways to meet human needs. Many of you will never accept or understand how rich a history Africa & her children have, especially in the U.S. where history has constantly been hidden or revised. My son once got sent to the principal’s office for challenging his fourth grade teacher’s ignorant lesson on American slavery in which she said, “White people had to bring Black slaves to America because they were swinging from trees & didn’t know anything. They couldn’t communicate with each other & didn’t even know how feed themselves or use the bathroom.

They didn’t know how what animals were & would’ve gotten hurt if white people had left them all on their own, so slavery was invented to help them.” She really repeated that ignorant lesson to my face, & was angry because my son reminded her that many African civilizations predate the European invasion. He’s homeschooled now & understands that even his teacher had been poorly educated. Do your own research & don’t be like that teacher!