How a Pennsylvania gal fell in love with Nevada

30 March 2018 – Deirdre Clemente

2018 annual meeting, Las Vegas Series 2018, community history, sense of place, environment, profession, employment, conference

Deirdre Clemente at Walking Box Ranch, Nevada. Photo credit: Deirdre Clemente

Editor’s note: This is the fourth in a series of pieces focused on Las Vegas and its regional identity which will be posted before and during the NCPH Annual Meeting in Las Vegas in April.

I grew up scouring the grasses around the Juniata River for arrowheads and I hunted down second-hand fur coats in every rusty, steel town in western Pennsylvania. My first post-PhD. gig was a job I loved: the curator of the Italian American collection at the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh.

I am a Pennsylvanian.

And I’ve fallen in love with another.

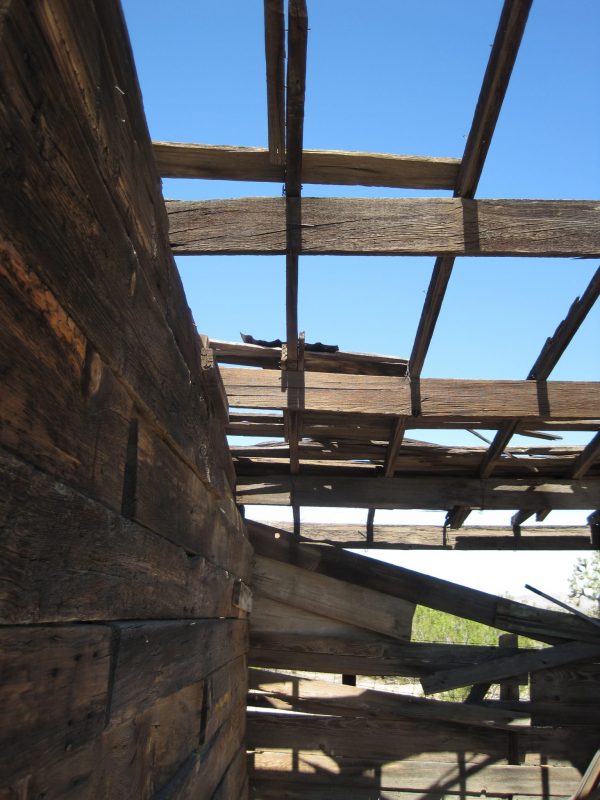

Shed where Clemente and her students worked in Nevada. Photo credit: Deirdre Clemente

Public history is inspired by place, and Nevada inspires me. In the past seven years, I’ve done some exciting public history here. My graduate students and I cataloged and organized the archives of the Culinary Union, whose Las Vegas chapter is one of the most powerful unions in the country. We worked in a tin-roofed shed, tucked behind their offices in early May. It was insanely hot.

We’ve held costume exhibitions featuring a Flying Elvis jumpsuit (complete with opened parachute) and Frank Sinatra’s tuxedo. Perhaps the most “Vegas” of my public history work here was the tiffany-set rhinestone extravaganza, Too Much of a Good Thing is Wonderful: Liberace and the Art of Costume. It ran for nine months at The Cosmopolitan.

But before all of those projects, there was a ranch and a lonely Pennsylvanian. I wasn’t so much lonely as never really alone, which is its own form of loneliness. I was overwhelmed: my husband, three kids under four, a new house, a new job, a new life. I missed my aunts, cousins, and sisters back in Pittsburgh. I learned lots of things about Nevada that first fall I was here. I learned to avoid the roads when it rains. I learned that any day under 100 is a good day. I learned that there really are seasons here, and you can smell them in the desert.

Walking Box Ranch, Nevada. Photo credit: Deirdre Clemente

Walking Box Ranch fell into my lap an afternoon in late August. I was about a month into my assistant professorship and I was on the hunt for a project for my public history methods course. “Hey, maybe your grad class can get involved with the Walking Box Ranch,” chirped my colleague Andy Kirk, as he rustled into his sparsely-yet-stylishly decorated office. “It was Clara Bow’s ranch, about an hour southwest of here. The public history program has worked with them before.”

The greatest face of the silent screen owned a working cattle ranch in the middle of the Nevada desert? Well…I guess.

The moment I walked on the property, my life and career changed. The management of the property was at the time a collaboration between the Bureau of Land Management and UNLV’s Public Lands Institute, which oversaw the ranch house, barn, and material culture. Since its establishment in 1932, the property went from the second largest ranch in Nevada under Bow and her cowboy-film star husband Rex Bell to a smaller family ranch to a vacation house for a mining executive’s wife, who was really into its maintenance.

Walking Box Ranch. Photo credit: Deirdre Clemente

This place was cool, and better yet, it was run by geologists and biologists, who knew everything about the always-discussed-but-never-spotted desert tortoise, but very little about the cultural significant of the ranch. Along with my graduate students, for an entire semester, we taught and learned.

Students divided themselves into project teams. The material culture team surveyed and researched more than a dozen Navajo rugs from the 1930s that were used at the property. They developed storage and display plans to best preserve the integrity of the rugs. Our cataloging team cleaned, cataloged, and stored nearly one thousand ranching and blacksmith tools that had been kept in a shed for the last half century. Our education team collected and synthesized information on the ranch, its history, and its significance to the region. They wrote lesson plans for high school students, produced dossiers of research, and one afternoon in December 2011, they lead an on-site walking tour that turned into quite the local event. It was amazing and encapsulated all the reasons I do public history.

After the Walking Box project, I never really looked back. Sure, I go back. Pennsylvania is filled with people, places, and food I love. But life is different now. I no longer feel like I am cheating when I tell everyone who will listen just how much I love my city and my state and my job.

Could you call me a Nevadan now? Well, my driver’s license and collection of cowboy boots certainly suggest so. Yes. I am a Nevadan now.

~Deirdre Clemente is the director of the public history program at UNLV where she studies clothing and cultural change. She is the author of Dress Casual: How College Students Redefined American Style (UNC Press, 2014). For more on her scholarship and public history work, check out www.unlvpublichistory.com and www.deirdreclemente.com. Clemente’s Twitter handle is FitzFash and she’s on Instagram at: unlvpublichistory and deirdreclemente1920