Introducing the Guantánamo Public Memory Project

17 June 2013 – Liz Ševčenko

“I sat there in my chair listening to the comment, ‘I don’t know much about Guantánamo,’ follow nearly each of my peers’ introductions, myself included,”

Marnie Macgregor, University of Minnesota

Marnie was joining over 100 other students from around the country in a national experiment in public history and public dialogue. The Guantánamo Public Memory Project was launched in June 2009 by the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience – together with military personnel, historians, legal advocates, and others — to raise awareness of the base’s long history and foster dialogue across difference on its future. Faced with the challenge of combating apathy and amnesia, the Project took a gamble: give the most responsibility to the people who know the least, and invite them to build their own understanding along with the rest of the world’s.

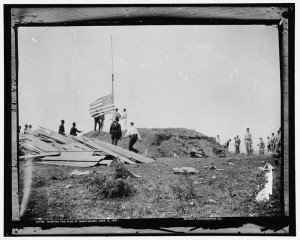

The US Naval base at Guantánamo Bay, or GTMO, has been forgotten, remembered, and forgotten again for more than a century. Long before Obama asked of GTMO, “ ‘Is this who we are?’ ”[i] this tiny spot in Cuba has been a battleground for American identity and values. It has defended and defined America from the War of 1898 to the Cold War to the War on Terror. The 1903 lease – valid indefinitely – grants Cuba “total sovereignty” but the US “complete jurisdiction and control,” creating a legal black hole into which generations have fallen. It’s detained Haitian and Cuban refugees outside US law; been a beloved home for military families; and offered the best jobs around for Eastern Cubans. It has been “closed” before: such as twenty years ago this week, on June 19, 1993, after Haitian refugees with HIV, cleared for asylum but barred by their disease, staged a hunger strike that captured the world’s attention. It’s been a legal laboratory for issues from immigration to public health to national security. New construction’s just been completed on a major new facility for holding refugees – reminding us that even if this Guantánamo closes, as soon as we forget about it, another will open.

From its new hub at Columbia University, the Project brought together 11 public history and museum studies programs to collaborate on a student-led exhibit on GTMO. In 2012, each program: taught a course on GTMO’s history, using Project material; worked with students and the Project’s designer to create one of 13 exhibit panels; created digital exhibits; and conducted hundreds of interviews.

To create the exhibit, students – and faculty – had to confront their own widely different views on this place, and how to talk about them. Through the blog, video conferencing, and class discussions, participants wrestled with their peers across the country on central challenges the Project posed for public history:

What is the role and responsibility of public historians handling contested, current histories? Jeremy Wells of ASU argued “we need to… strive to inform constructively through representing Guantánamo objectively.” But for Ria Mirchandani of Brown University, “There is a trade-off between being well informed on the matter and being objective. To an extent I feel that the more I know, the less objective I become; but I am fine with this because it’s better to hold justified biases than be ignorant.”

What do we mean by “multiple perspectives?” What do they all add up to? “Everything was so free down there,” remembers Anita Lewis Isom, of growing up at GTMO in the 1960s. “I would give anything to go back.” Students struggled to square this with stories of detention, like those University of Miami students recorded with Cuban refugee Sergio Lastres: “it was a prison.” “How can these two opposing viewpoints coexist?” wondered Kavita Singh of IUPUI.

The Project tried to create space for students to explore conflicting accounts, or to make a strong argument based in rigorous research that owned up to its subjectivity. Each panel, curated by a different student team, has a different theme and time period, but also a different take. Each includes a statement titled “Our point of view,” in which student teams shared “where they were coming from” — how their individual identities or community contexts shaped their interpretive approach. The result, as UMass Amherst’s GPMP faculty David Glassberg put it, is an exhibit that’s “in dialogue with itself.”

But how can we foster dialogue on such a sensitive topic? And about what, exactly? Some felt strongly that certain questions should not be up for debate, such as whether torture occurred at Guantánamo, or whether torture is justified. Crafting questions became a central challenge for each student team. Panels were “titled” with questions; derived from GTMO’s history, but with implications across place and time. Brown University’s panel on Haitians at GTMO asks, “What is a refugee? What makes a refuge?” Students also invited audiences to “Shape the Debate” by voting and commenting via text message on questions like (by Rutgers): “Is the US an Empire?”

Guantánamo Public Memory Project Exhibit. Jan., 2013. Washington Square, NYC. Courtesy Picture Projects.

After opening at NYU in December 2012, the exhibit is now traveling to each of the communities that created it – with more universities contributing along the way. It’s showing in public spaces, campus galleries, and museums like the International Civil Rights Center and Museum (through UNC Greensboro). At each stop, hosts place GTMO in their own local context, opening different conversations about why GTMO and its history matters here at home. This month, the UC Riverside team explores connections between Guantánamo and the California prison system by pairing the GPMP exhibit with contemporary art at the California Museum of Photography. The University of West Florida will enhance the GPMP exhibit with artifacts from local families remembering GTMO’s close-knit naval community.

This post launches a series of reflections from professors, students, and people who lived at GTMO on the challenges — and the possibilities — the Project poses for public history.

Join this experiment and shape the debate by bringing the Project to your community. You can host the exhibit, open public dialogues, and connect your courses. You’ll find lots of opportunities for students to contribute new reflections and research using Project resources. Contact [email protected] for more information.

~ Liz Ševčenko directs the Guantánamo Public Memory Project from Columbia University’s Institute for the Study of Human Rights. She launched the GPMP from the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, of which she was Founding Director. Before organizing the Coalition, Ševčenko was a Vice President of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum.

[i] “Obama’s Speech on Drone Policy,” as printed in The New York Times, May 23, 2013 and accessed at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/24/us/politics/transcript-of-obamas-speech-on-drone-policy.html?pagewanted=9&_r=2&ref=world&

Hey you used one of my pictures, Kathy and Sam Phillips our neighbors in Nob Hill! And My playhouse!

Any interest in sending the exhibit to GTMO and collecting feedback from current residents? My sister lives there and would love to help coordinate this.

My family lived on the Base from 1962-1983. We experienced the Cuban Missile Crisis/Evacuation; severing of the water pipe from Cuba; and the rest of the history captured for our duration. As a military dependent during the 60’s through early 80’s, some very special moments have forever been captured in our hearts and minds that have forever been embedded in our conscience.