Our Side of the Tracks: Community Curation of Black History in Acworth, Georgia (Part 2)

09 March 2021 – James Newberry

The second of two installments in a series exploring the development of the “Our Side of the Tracks” exhibit at Doyal Hill Park in Acworth, Georgia. Part One described the origins of the project, starting with the partnership between Kennesaw State University’s Department of Museums, Archives and Rare Books and the city of Acworth, Georgia, as well as providing background on developmental changes over the past 40 years in Acworth’s historically Black neighborhoods. Part Two explores the outreach phase of the curatorial process, which built on initial research and ultimately turned the exhibit in a new, more personal direction.

Helen Hill in front of her mother Lenora Harden’s in-home restaurant, Harden’s Cafe, Cherokee Street, Acworth, Georgia, 1954. Image credit: Kennesaw State University Archives

“You wouldn’t believe how Acworth has changed,” said former resident Helen Hill, who sold her home to the city of Acworth in the 2010s, making way for a new recreation complex. When Hill visits Acworth today, she barely recognizes the neighborhood northeast of the railroad tracks that she adored as a child growing up in the 1940s. She misses the tight-knit community that developed there in the century after the Civil War, nurturing multiple generations of her family and inspiring the “Our Side of the Tracks” exhibit. Hill’s contributions to the exhibit were unique and—like the contributions of others— they complicate accepted narratives about a changing community. The differences in each individual’s experience enliven “Our Side of the Tracks,” elevating it from a static memorial to a thoughtful reflection on an unsettled past.

At Hill Park’s dedication in December 2020, I held my breath as the sculptural centerpiece and exhibit were unveiled. The panel-based exhibit lines a path from Cherokee Street to the Rosenwald School Community Center and explores Acworth’s historic Black community.[1] My team in the Department of Museums, Archives and Rare Books (MARB) at Kennesaw State University curated the exhibit and made use of photographs and stories shared by members of the community, many of whom were present at the dedication. Contributing their time and trust in a tumultuous year, community members made “Our Side of the Tracks” a better exhibit, personalizing stories of their ancestors and broadening our knowledge of Acworth.

At the start of the exhibit development process in June 2020, the city of Acworth requested the following topics for exploration in the exhibit: early Black businesses, spiritual life, education, and public service. Preliminary research gathered from materials provided by the city—as well as property records, local archival collections, and historic newspapers such as the Marietta Daily Journal and the Atlanta Daily World—supplied our team with the content necessary to fulfill our client’s request. But feedback from community members pushed the exhibit beyond its initial parameters. As part of the outreach process, we contacted more than fifty people and visited fifteen (some multiple times) in Cobb, Fulton, and Paulding counties. Because of the public health emergency related to COVID-19, our socially distanced visits took place in the open air—on porches, carports, and driveways. We wore face masks as well as plastic gloves, enabling us to handle personal items and digitize photographs on a portable scanner.

For the outreach process, our team sought to confirm our existing research with individuals and families who have firsthand experience. We also hoped to gather any additional primary source material that would enhance the design of the outdoor exhibit panels. While both goals seemed fairly straightforward at the outset, they would soon propel the project into new territory as we engaged community members, who contributed their memories and a range of materials that complicate traditional narratives of local history and memory in Acworth.

Working with current and former residents of Acworth, our team identified social connections and cultural traditions as the most enduring points of cohesion for a community dispersed over time. The Black Acworth Community Homecoming celebration, which ran from the 1950s to the 2010s and included meet-and-greets, religious services, picnics, ball games, parades, and social dances for young people, was a cherished event for local residents and family and friends spread across Metro Atlanta and throughout the country during the Great Migration. “My cousins in Cincinnati and Detroit always set their vacations in time for homecoming,” said Charlie Mae Griffin, a 96-year-old resident of Acworth.

Other social events such as birthday parties and dances at the Rosenwald School Community Center or baseball games at Coats and Clark Field came up often in our conversations. After Claude “Moochie” Johnson played on the all-Black Eagles baseball team with friends, he decided to start a team for kids in 1963. Instead of integrating the white youth league as Johnson suggested, the city agreed to provide equipment and uniforms for Johnson’s Warriors. He coached the team in two groups, a blue team for younger kids and a red team for teenagers. Ray Charles Kemp, who played on the blue team as a nine-year-old, recalled games in Marietta, Cartersville, Calhoun, and Dalton, Georgia, where a “World Series” took place.

Acworth’s color line was clear, even for the few Black individuals and families that lived in other parts of the city. Evelyn Gragg grew up near a white settlement outside town in the 1910s. While she walked to school with white children, Gragg separated from them at the railroad crossing to attend the segregated school in the Black community. Because there was no Black high school in Acworth, Gragg moved to Atlanta to attend Booker T. Washington High School but later quit to become a domestic worker; she felt that her grandmother needed her back at home in Acworth. In an oral history interview conducted in 2009 and archived at Kennesaw State, Gragg said, “I always kept myself in my place. I never did try to go beyond.”

When Florence Rice Bates started her food service career in the kitchen of the Silver Trolley diner in the 1940s, she was still barred from entering the dining area. Acworth’s Legion Theatre was located next door and required Black moviegoers to enter through a side door and sit in the balcony. As Civil Rights activists challenged similar discrimination just thirty miles south in Atlanta, the ongoing struggle felt remote to some Acworth residents, who were accustomed to the community’s racial status quo. The news of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in 1968 shook the community, however. “We had to watch it in school on TV,” said City Alderman Tim Houston. “It was something to see the reaction of everybody else. Many people were mad, really mad.”

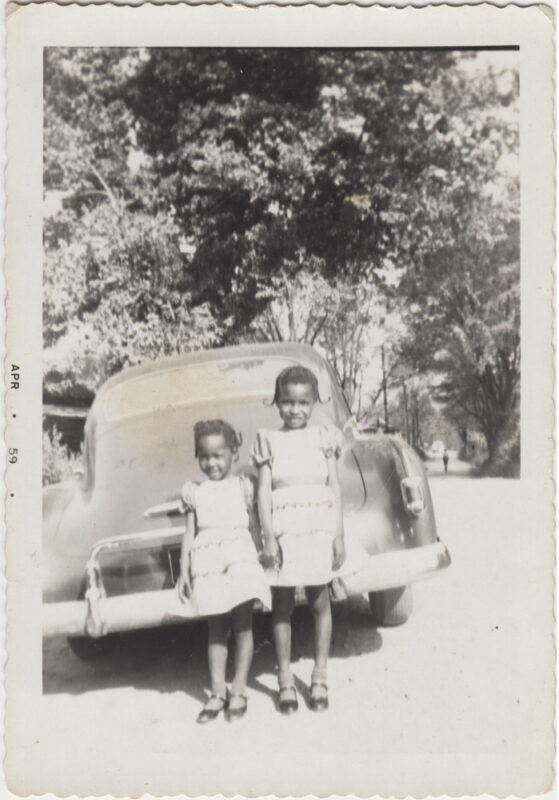

Beverly Patton (right) and her sister Deborah Griffin on Moon Street in Acworth, Georgia, April 1959. Image credit: Kennesaw State University Archives

Beverly Patton’s name came up numerous times as our team worked with members of the community. “Taking you out of Acworth would be like taking a fish out of water,” a friend once told her, and it’s true. Patton was the first in her family to earn a college degree, graduating from Kennesaw State in 1983, but she always remained in Acworth. She worked as a manager for the U.S. Postal Service and serves as an associate pastor at Zion Hill Missionary Baptist Church today. She coordinated the Black Acworth Community Homecoming celebration for over a decade and served on Acworth’s local preservation committee as well as the NAACP’s Cobb County Branch.

Patton lives in her parents’ former home in the old neighborhood, transformed since her 1950s youth. Childhood photographs show Patton and her seven siblings walking along the dirt roads that crisscrossed the community. Like other current residents and exhibit contributors, Patton sees much of the community’s new development as inevitable. “There’s definitely been a loss,” she said, “but some people in my generation just didn’t want to have anything to do with the community, or they couldn’t take care of their parents and grandparents’ old houses anymore and sold them to the city.”

Patton’s commitment to preserving local history finds greatest expression in her extensive and growing collection of photographs. She shared more than 150 photographs, documents, and other materials for use in the Hill Park exhibit project, but more significantly, her outsized contribution created the basis for a permanent digital collection of photographs and other materials documenting the historic Black community in Acworth. Now archived at Kennesaw State, the Historic Black Acworth Image Collection is an ongoing digitization project that currently includes more than 465 images shared by Patton and others. Linked via a QR code on the Hill Park exhibit’s introductory panel, the collection is accessible to view online at https://soar.kennesaw.edu/handle/11360/4097.

The Historic Black Acworth Image Collection and the new “Our Side of the Tracks” exhibit at Hill Park illustrate how the exhibit development process can change through the shared authority and engagement of community members and stakeholders. While I worried what guests at the park’s dedication in December would think of this or that image, quote, or story, I soon realized that the exhibit no longer belonged to me or the curatorial team. After the unveiling, we gave up any remaining control over the project to the individuals and families that made it possible.

As Patton said, “I do whatever I can to acknowledge the Black community, so that it doesn’t die out historically and so that it will be forever remembered, even if it’s in books or photos. I’m still willing to do whatever I can to carry that through, to make it known that the Black community was here.”

~James Newberry is Special Projects Curator for the Department of Museums, Archives and Rare Books at Kennesaw State University.

[1] Acworth, Georgia, sits on land taken from the Cherokee Nation after the U.S. Government forcibly removed native peoples in the 1830s.