Preserving the pandemic: archiving history as it happens in Westmoreland County, PA

22 October 2020 – Pamela Y. Curtin and Lauren Churilla

archives, collaboration, covid-19, 2020 Archives Month Series, digital collecting, Community partnership

Editors’ Note: This is one in a series of posts about the intersection of archives and public history in the age of COVID-19 that will be published throughout October, Archives Month in the United States. This series is edited by National Council on Public History (NCPH) board member Krista McCracken, History@Work affiliate editor Kristin O’Brassill-Kulfan, and NCPH The Public Historian co-editor/Digital Media Editor Nicole Belolan.

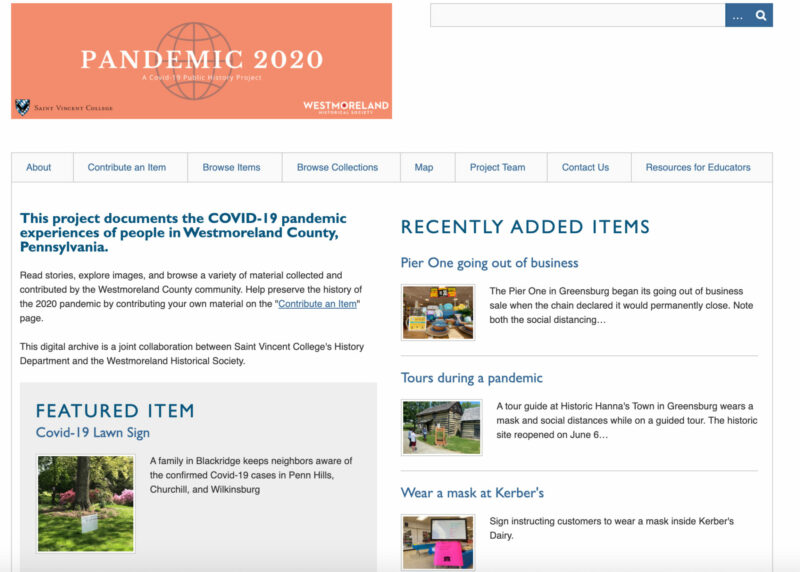

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged history organizations and post-secondary institutions to face a public health crisis while continuing to carry out their missions. In Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, colleagues across fields, each with unique skills, knowledge bases, and goals, came together to meet the needs of their communities. In April 2020, the History Department of Saint Vincent College and Westmoreland Historical Society launched Pandemic 2020, a digital archive documenting local experiences of the pandemic in real-time. This project brings together the knowledge and skills of professionals from different backgrounds in our local area.

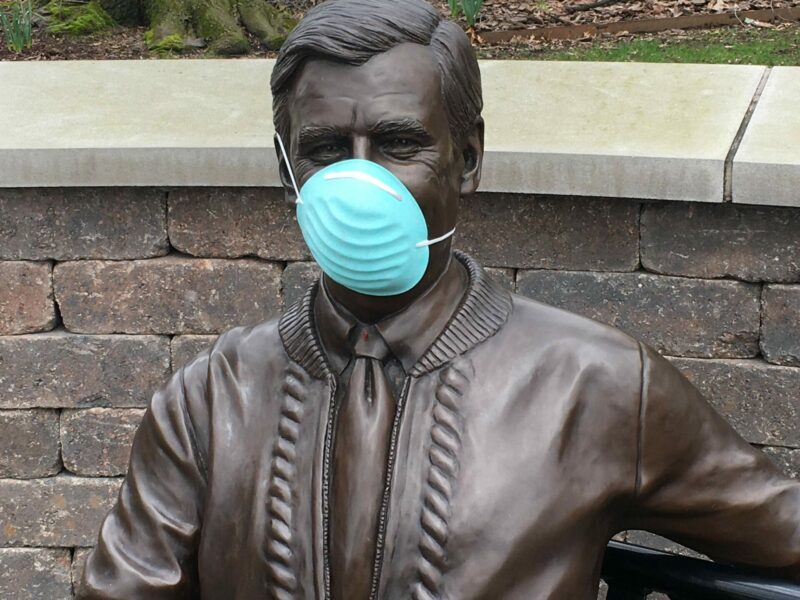

A sculpture of children’s television pioneer Fred Rogers in his hometown of Latrobe, Pennsylvania, shows how to be a good neighbor by wearing a mask. Photo credit: text “Helping a Neighbor,” Pandemic 2020: An SVC Covid-19 Public History Project

Westmoreland County is an exurb of Pittsburgh in southwestern Pennsylvania, a region that historically supported Pittsburgh’s steel industry through mineral extraction. Westmoreland County suffered from the collapse of manufacturing and heavy industries in the late 1970s to 1980s, which in turn initiated a population decline. Recent revitalization efforts are working to revive downtowns, support small businesses and farms, and attract tourists and residents to local historic sites and parks. The county is home to both suburban and rural communities, with many residents tracing their roots back to early agriculture and industry, along with transient populations of students at smaller universities and liberal arts colleges.

When Pennsylvania closed non-essential businesses in late March, Westmoreland County, like many other communities across the nation, experienced widespread concern about the virus and its potential long-term social, cultural, and economic effects. Professors at Saint Vincent College saw their semesters cut short and abruptly transition to online classes while listening to the stories of students experiencing sudden isolation and a loss of community. The Westmoreland Historical Society’s research library and museum closed to the public, educational programs were suspended, and their Revolutionary War-era historic site, Historic Hanna’s Town, delayed opening. With these institutional closures came almost daily notices of business shutdowns, empty store shelves, and unease about the unknowns to come. As everyone adjusted to this change, we became aware that recording history as it happened provided a unique opportunity for our community and for us as historians.

The usually busy playground at Keystone State Park in Derry, Pennsylvania, is closed due to public health concerns. Photo credit: “Playground at Keystone State Park,” Pandemic 2020: An SVC Covid-19 Public History Project

Both professors and museum professionals in Westmoreland County, separately yet concurrently, considered ways to respond to the pandemic. The history department at Saint Vincent College wondered if there was a way to authentically capture the experiences of a college community that had not faced an emergency closure since the 1918 influenza pandemic. Staff at the Westmoreland Historical Society grappled with cancelled programs, worked to find new ways to reach their socially distanced audiences, and also heard the echoes of the 1918 pandemic.

Within the first few weeks of lockdown, conversations between partners that began as casual check-ins turned into detailed planning sessions. We began researching ways to document the changes in our community while giving members of that community an outlet where they could share their struggles, joys, and daily experiences. We were aware of many people before us who have pioneered rapid response collecting, such as the Smithsonian Institution’s efforts to document current events. We noted other museums and historical societies responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the Wisconsin Historical Society’s COVID-19 Journal Project and the Heinz History Center’s Experiencing History effort to collect digital and physical objects. We were also inspired by broader community-based collecting initiatives like the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s History Harvest.

Through our planning sessions, we created a project that fulfilled common goals. The project’s scope would encompass all of Westmoreland County, fulfilling both the Historical Society’s county-wide mission and align with the history department’s efforts to expand their Public History major, develop digital humanities initiatives, and engage the local community. We decided on creating a digital archive that would allow the public to freely upload and view contributions. This allowed us the opportunity to harness digital tools that we had been wanting to experiment with, while avoiding the potential health issues related to collecting physical objects.

Over the course of a few weeks, we built the website using Omeka (and tested it out with many of our friends, family, and colleagues) to make sure that the product we built served our project’s collection goals while providing ease of access.

The Pandemic 2020 digital archive is user friendly for both its creators and contributors thanks to Omeka.net. Our long-term plans include expanding collections, adding exhibits, and developing more educational materials.

The resulting product debuted in early May after several weeks of working sessions, web development, and troubleshooting. What emerged from our collaboration was a digital archive to document the experiences of local people living through the pandemic. This is done through collecting personal recollections, photographs, artwork, videos, sounds, social media posts, recipes, music, and all sorts of digital media that express the human condition in times of crisis. The archive is preserving stories of struggling college students, pictures of closed signs on local businesses and piles of homemade masks, and the sounds of an organ emanating from Saint Vincent’s empty basilica on Easter Sunday. These stories, sights, and sounds are familiar today but fleeting in the broader sense of time, and our digital archive aims to collect and preserve them for the future.

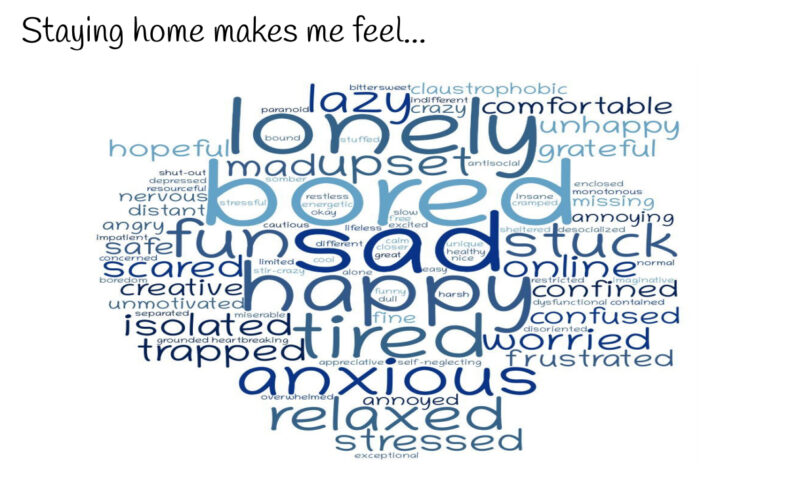

Students in the 7th grade at Greater Latrobe Junior High School were asked to imagine how to describe the pandemic to someone 50 years in the future and created word clouds with their responses. The archive accepts a variety of materials that help convey experiences of the pandemic. “7th Grade Word Clouds,” Pandemic 2020: An SVC Covid-19 Public History Project

Our partnership has thrived by recognizing our common goals and the strengths, expertise, and resources across our respective organizations. Saint Vincent College provides departmental and technical expertise through the public history faculty. Undergraduate work-study students seek contributions from the college community and help with metadata entry. The Westmoreland Historical Society helps maintain the website, solicit contributions from the broader public, and will use the archive as a starting point for collecting physical and digital objects related to the pandemic. We have promoted the archive on social media, through local newspapers, a regional visitors bureau, and a local radio show and podcast. We are actively collecting material for the archive by taking photographs, linking news articles, uploading social media screenshots, and developing lesson plans for educators. The archive currently includes over 100 contributions from across Westmoreland County. We plan to expand our efforts by cultivating new partnerships with community groups, conducting oral histories, curating digital exhibits, and collecting physical objects. Collaboration has allowed us to bring the project into fruition and ensure its longevity.

We have collected photographs that show how the community landscape changed over time, with this sign supporting frontline workers being an inspirational addition. Photo credit: “Thank you, Frontliners,” Pandemic 2020: An SCV Covid-19 Public History Project

As historians, we realize that it is challenging to know what material and information will be relevant in the future. As time goes on, we will review and refine the project’s goals to ensure we are going in the right direction. We are collecting with breadth and depth, forging more community partnerships and getting the word out so that the project stays active and relevant. Pandemic 2020 embodies how people in Westmoreland County are experiencing the pandemic and documenting history as it happens. The archive gives both our college and historical society a new purpose as we, too, struggle with these unexpected changes. The archive itself, as well as its contents, is representative of an unprecedented moment in history that we hope becomes an invaluable resource for future understandings of life in our area during a pandemic.

~Pamela Curtin is the education coordinator at the Westmoreland Historical Society and a lecturer in public history and museum studies at Saint Vincent College. She has a BA in history from Saint Vincent College and MA in public history from West Virginia University.

~Lauren Churilla is the director and curator of the Foster and Muriel McCarl Coverlet Gallery at Saint Vincent College and a lecturer in US history and public history at the college. She is a doctoral candidate at Carnegie Mellon University.