Reflections on Stonewall: Fifty years after the “Stonewall Riots,” not much has changed about how we commemorate LGBTQ+ history

28 January 2020 – Megan Crutcher

intersectionality, advocacy, community history, memory, sense of place, National Park Service, LGBTQ history

Stonewall Inn, 2019. Photo Credit: Megan Crutcher

Editor’s note: Following after two important NCPH publications related to LGBTQ history: the LGBTQ issue of The Public Historian (https://tph.ucpress.edu/

On a rainy Sunday in New York City, I was looking forward to visiting some sites on my personal path less traveled, like the Stonewall National Monument that commemorates the 1969 Stonewall ‘riots’ that helped spark the LGBTQ rights movement. I wandered in around 2pm, awed by this unassuming site of memory. The only other people inside were the bartender, an elderly man, a small group of young people in the back, and a couple of guys who seemed to be on a date. I sat down close to the door, intending to read my book. As I sat down, the elderly man slurred, “It’s on me!” I took the Brooklyn IPA, which came in a special plastic cup with a rainbow heart and the number “50.” The bartender and I briefly talked about the events and demographics of the bar: weekends tend to host dance parties full of 20-somethings, while weeknights host your standard happy-hour crowd. We shared knowing smiles and twinkling eyes as the elderly man, who told us he was 85 years old, asked if we were Trump supporters. I said, “What do you think? We’re at Stonewall.” Unfazed, the man kept talking politics, then turned to me and said, “You know this is a gay bar?” To which I replied, “Well, sir, why do you think I’m here?” I left it at that, and kept reading. In some ways, Stonewall has always been a place that welcomed everybody with a knowing smile and a twinkle in their eyes.

The actual designated National Park Service (NPS) site commemorating Stonewall is located across the street at Christopher Park, another key location in the 1969 riots. The park is nice but underwhelming compared to its neighbor. The Stonewall Inn has become the central historic location for the U.S. gay rights movement. Indeed, with some exceptions, it was the queer “shot heard round the world.” In some sense, Stonewall’s identity as a historic site is not evident in its operations. Yes, it is a site of pilgrimage and memory, but it is also still a functioning bar and club like any other in New York. Its role as a useful space gives it a greater emotional power; there are few national monuments that effectively make LGBTQ+ history a part of life and remain useful in the current day.

But the story of this historic monument is still so overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly male, overwhelmingly G at the exclusion of the L, B, T, Q, and others. Granted, I didn’t feel unwelcome in this space as a queer woman. But I did feel very female and very young. As I sat there and read for about two hours, nursing my IPA, the bar steadily filled. By the time I left, there were about twenty-five other people there. All of them were men. Almost all were white. Most of them came in pairs or groups. Most of them looked between 30 and 60 years old. And then there was me, the queer bisexual 20-something white woman.

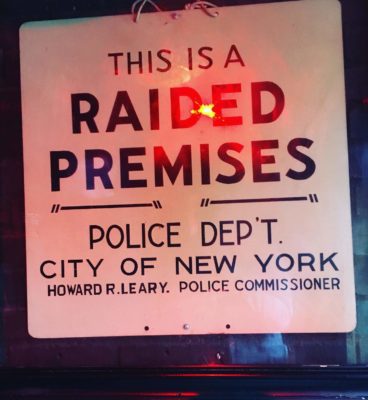

Notice posted inside the Stonewall Inn. Photo credit: Megan Crutcher

At Stonewall and its nearby related sites, the focus is still on gay men (with an unspoken prefix of ‘white’.) A walking tour of the village created through a partnership between the National Park Service and NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project focuses almost exclusively on Stonewall’s importance for gay men. Out of 17 stops the walking tour has only one lesbian bar and one site dedicated to LGBTQ+ women. They do have a “suggest a site” button on the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project website that would allow community members to contribute to the telling of more diverse stories. Another LGBTQ+ walking tour by NYC LGBT Historic Sites has only two lesbian-focused sites. Interpretation inside Stonewall consists mainly of a few photos and newspaper articles framed on the wall about the Christopher Street Parade in 1969 and the “riots.” Most photos depict white men. But women who defined the LGBTQ+ rights movement—trans women like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera; lesbians like Stormé DeLarverie, Barbara Smith, Rita Mae Brown, and Pauli Murray; bisexual women like Brenda Howard, and thousands more—are completely absent.

This is not to say the NPS has ignored LGBTQ+ history and heritage in general. In fact, the NPS’s landmark study conducted in 2016 has served as a major source and catalyst for many cultural institutions including LGBTQ+ history like never before. Nor has the public history field neglected to tell LGBTQ+ stories. Before and after the 2016 NPS study there were numerous initiatives for LGBTQ+ history such as LGBT Religious Archives Network at Berkeley, the blog Notches, NCPH’s own posts on the topic (such as here and here), the American Alliance of Museums’ LGBTQ Welcoming Guidelines, and more. But like many traditionally ignored histories, full inclusion of LGBTQ+ history continues to be a political battle as well as a cultural and historical one. LGBTQ+ people and histories are still marginalized, despite these admirable and necessary changes in those histories’ telling. It was just in 2016 (four years ago) that the president of the National Parks Foundation declared that LGBTQ+ history is American history. Looking at Stonewall, comparing the homophobia that is all too prevalent even in the early months of 2020, one cannot help but wonder: how much progress have we made in four years?

The tours mentioned above are self-guided. Most locations are privately owned and visitors cannot enter. The brief site descriptions on the walking tour map leave visitors largely to draw their own conclusions about the significance of this history. The typical fixtures of a National Park are almost completely absent at Stonewall. partly because it is a new site but partly because the bar itself is not an NPS site. The park across the street is what is technically designated the NPS site, raising a host of other questions regarding historic landmarks, National Parks, and private ownership. The bartender inside Stonewall was entrusted with an NPS passport stamp that allows visitors to collect the stamps even though the Stonewall Inn is a private entity. The Christopher Park is maintained by volunteers, like many city parks its size. Volunteers also carry out historic preservation with the Greenwich Village Historical Society. The NPS website events page reveals that there is only minimal programming at the site and gives little in terms of “things to do.”

To have any LGBTQ+ national monuments is a tremendous feat in our era of seemingly increased bigotry. But to have a national monument that tells a sanitized narrative of white, gay men seems like a nominal acknowledgement of LGBTQ+ history separate from any deeper supportive action. This could be remedied with more solid historical interpretation. Without more historical interpretation of Stonewall itself, whether inside the bar or in Christopher Park, how are visitors to understand the importance of this site? Even more, the interpretation that does exist excludes the diversity and intersectionality of LGBTQ+ individuals. Women, people of color, and people who have not fit the historically expected mold of queerness deserve to have a seat at the bar and to buy our own drinks if we feel like it. Is Stonewall National Monument making that place? It remains to be seen.

~Megan Crutcher is a master’s student in public history at Duquesne University and a practicing historic preservationist. Find her online at www.megancrutcher.com and tweeting at @crutcher_megan