Reflections on the Mall

26 November 2020 – Taylor Noakes

Reflections on the republic at dusk. Photo credit: Taylor C. Noakes

Washington, DC, felt familiar in a way that didn’t make sense; I had never been there before.

I am originally from Montreal and am now pursuing a master’s degree in public history at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. Growing up in Canada, the son of an American citizen, I always felt like I had a foot on both sides of the border. I thought it was an interesting time to come to America and want to become an American. Two and a half years later, my feelings haven’t changed, though I am acutely aware of the position of privilege that allows me to entertain such an option. I spent much of last autumn brushing up on American history and learning about the capital, its museums, and monuments.

An image of the city began to form in my mind, and I wondered how the city might tell me the story of America.

Looking out at the Watergate and the Kennedy Center, a bizarre thought came to me. How many times had I seen this all destroyed? Not these buildings specifically, but of all of Washington: by space aliens, by tidal waves or asteroids, or in endless iterations of terrorism.

In my mind, DC had always been framed by television and theatre screens.

Growing up, I felt privileged: my home had a window in the basement that every night showed me pictures of the Capitol, the White House, the Mall, and various monuments. I watched important people speaking of important things, importantly. None of the other kids seemed to have this kind of window. We watched an hour of American news each night as a family—Peter Jennings followed by Dan Rather—using commercial breaks as an opportunity for my endless stream of questions.

D.C. was the capital of the universe as far as I could tell.

As we made our way into the heart of the city a peculiar impression swept over me. It was as though the abstract idea of Washington, DC, was superimposed on the real city.

Images flashed through my mind: MLK addressing the masses during the March on Washington mixed with Forrest Gump running into the Reflecting Pool. Processions of presidential motorcades and countless inaugurations mixed with Kevin Costner’s Jim Garrison meeting Donald Sutherland’s Mr. X in front of the Capitol. As we drove past the White House, I noted its distance from the Lincoln Memorial and thought of President Nixon out one night for a casual talk with anti-war demonstrators keeping vigil at Lincoln’s feet. Was I remembering something that really occurred or was it a scene from an Oliver Stone film?

This phenomenon of superimposed images and ideas, all too often seemingly contradictory, colored and shaped my introduction to the United States. Despite the poisonous xenophobia so prevalent in our society, some of the very first Americans I met outside my friends, family, and new colleagues were refugees from sub-Saharan Africa whom I interviewed for an oral history class, and who had quite literally risked everything to be here. They were resolute in their determination to succeed, almost dismissive of the challenges they faced. The hard part, they told me, was already far behind them. Those interviews often left me speechless. I had no excuse, nothing to fear but fear itself.

Over the course of the first semester I became immersed simultaneously in American history and the debates, concerns, and considerations regarding how Americans learn, interpret, and come to understand their history. My classes felt like virtual tours of DC, moving from monument to museum, from one controversy to another. I found these conversations and course readings incredibly interesting; I began to wonder why commemoration didn’t seem nearly as contested in my birth country. I had never really thought of the social aspects of creating a memorial to the Vietnam War in an era characterized by renewed Cold War militarism and the lingering psychosocial effects and mass trauma of an enduringly unpopular conflict. I had never considered how the Smithsonian’s Enola Gay controversy may have impacted the design of the World War Two Memorial.

“Dixie” rings out from food trucks on The Mall. Photo credit: Taylor C. Noakes

All of Washington seemed to be one constantly shifting and evolving juxtaposition of all America was and wanted to be, all the greatness it was capable of, all the horror hiding in plain sight. Little details like all the food trucks lining The Mall blaring tinny electronic renditions of “Dixie,” or the homeless camped out in the public squares and plazas of the wealthiest nation the world had ever known. These odd combinations of images were everywhere I looked, from the lunar module standing across from intercontinental ballistic missiles at the National Air and Space Museum to the fragility and fallibility of the National Portrait Gallery presidents: more human than human.

Highs and lows: the Smithsonian’s ICBM gallery. Photo credit: Taylor C. Noakes

I wondered if there would one day be a portrait of the current president, and whether a critical reassessment of our leaders would precede or perhaps preclude its exhibition. I was excited by the prospect of future public history debates. It occurred to me that coming to terms with the last four years may necessitate a national conversation about the last four hundred.

Coming to terms with America felt like both a professional and personal requirement; I chose to come here, now, of all times. Maybe my grandfather was similarly conflicted when his Liberty Ship slipped into New York Harbor towards the end of the war—the big one—arriving not to start a new life but to get trained in bombing the Old World. He was fortunate; the war ran out before his luck did. No one told him to go home when it was over so he went to New Jersey instead.

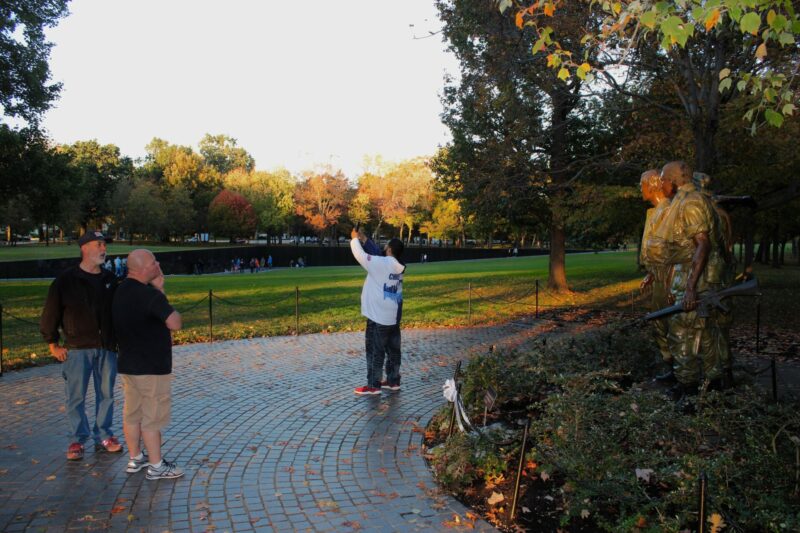

I looked high and low but couldn’t find the monument that said “you’re home here, come as you are.” For all the monuments to war and conquest, I couldn’t find anything dedicated to decency and democracy. The closest I could find to a peace monument was an absorbing apex of black granite cut into a grassy knoll. Far from inspiring, it was a subtle condemnation speaking volumes in stolid silence.

Visitors contemplate “The Three Servicemen” at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Photo credit: Taylor C. Noakes

I found great beauty and brilliance in DC’s monuments, but never where—or in the way—I thought it would be. Honest Abe may be seated in the Lincoln Memorial but he doesn’t seem to be at rest. I half expected him to leap up from his chair to get back to work. There’s so much left to be done.

Descending into the bowels of the National Museum of American History I considered what I might find. Evidently, no single building could house all of American history, but I was hopeful I would find something that neatly encapsulated the national experience.

Instead, I found the Batmobile.

My generation’s Batmobile, to be precise. The ’89 model. There it was, dimly lit and in the middle of the room. “Why’s that here?” asked my partner.

“I think it broke through the Confederate lines at Appomattox. . .”

I was eager to see everything else and dragged my partner this way and that. The original Star-Spangled Banner was impressive, as was the locomotive John Bull. The exhibits on the first ladies and the presidents felt like little more than collections of presidential memorabilia rather than any kind of critical analysis of the presidents or their accomplishments.

The Price of Freedom: Americans at War was another exhibit that had caught my attention during our classroom discussions of the evolution of public history in the nation’s capital, and I briefly considered the possibility this exhibit might try to communicate the scale of the sacrifice made by so many Americans in the pursuit of lasting world peace. Instead, we found a gallery of guns of ever-increasing lethality. We got as far as a flamethrower when my partner turned to me and stated she had had enough. An American by birth, she turned to reassure me: “We’re more than this.”

As I look back on it now, I find myself quickly overcome by an intense desire to see as much of America as I possibly can, as soon as I can. I regret not having made more trips to DC in the few months between when I moved here and the outbreak of the pandemic. I have a vague idea about how much I didn’t see that I find rather irritating. I was enchanted in the way I had hoped. It is as grand and inspiring as it was when it formed the backdrop of nightly newscasts and the conversations I enjoyed with my parents as a child. The impression I had formed of the city as an adult was confirmed and challenged by what I saw and experienced. I still feel that Washington may in fact be two cities: the national capital of a sovereign people on the one hand, and the seat of a globe-spanning empire on the other. I saw hopes and dreams as well as the dread and despair: the uneasy coexistence of the glory and the nightmare.

We’ll be back after these messages.

~ Taylor C. Noakes is originally from Montreal and is a graduate student in public history at Duquesne University. He spends his free time trying to be an iconoclast. His reporting, criticism, and commentary have been published in periodicals on either side of the 49th parallel.