Science and disability Q&A: Part 1

05 September 2019 – Nicole Belolan and Jessica Martucci

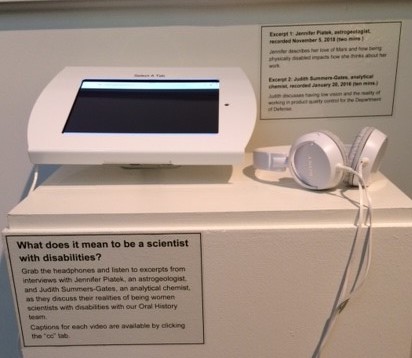

“What does it mean to be a scientist with disabilities?” exhibition detail. Photo credit: Jessica Martucci (used with permission from the Science History Institute)

Editor’s note: this is the first in a two-part series based on a conversation between our Digital Media Editor, Nicole Belolan, and Jessica Martucci, a researcher at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Nicole Belolan: Before we delve into the Science and Disability project, tell us about the Science History Institute (including its recent name change) and your position.

Jessica Martucci: The Science History Institute (formerly known as the Chemical Heritage Foundation) collects, interprets, and shares stories about the history of science through our museum, library, oral history, and archival collections. We also offer academic fellowships, public programs, and training that help inform scholarship in the history of science and spur public engagement with our work. As a researcher at the Institute, I work to cultivate more diversity and inclusion into our collections, to produce scholarship that highlights and adds to our collections, and to work with my colleagues to promote public engagement with our collections through our digital, museum, and programming spaces.

NB: How did you get interested in science and disability?

JM: I had some exposure to disability history as a graduate student in the history of science, but my first significant area of research didn’t engage with disability at all. My initial work focused on the history of motherhood and breastfeeding. Around the time when I was completing my first book, Back to the Breast: Natural Motherhood and Breastfeeding in America, I was also beginning a new postdoctoral position in the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy. The literature that I started encountering through my work in bioethics helped spur my interest in developing a project on disability. I was shocked that there was a literature in the ethics community on whether or not people with disabilities ought to receive the same kind of medical care as everyone else. In fact, assumptions about what it means to experience a disability are embedded throughout our healthcare landscape. I began thinking about an oral history-based project that would allow people with disabilities to assert their own voices into both historical and contemporary debates in healthcare, science, and technology.

NB: How does the Science and Disability oral history project relate to SHI’s mission?

JM: When I heard about an opportunity for a fellowship in oral history to examine the experiences of people with disabilities in science as practitioners, it sounded perfect. I was immediately attracted to the project’s potential for flipping the dominant narrative I have found in discourses, in which people with disabilities, when discussed at all, are seen primarily as consumers of scientific, medical, and technological expertise and products. From the outset, this project appealed to me for its construction of people with disabilities as active knowers and experts in science, which is such a simple shift in perspective and yet has this wonderfully disruptive effect on how we talk about knowledge.

NB: Tell us a bit about the oral history project and the related museum exhibit.

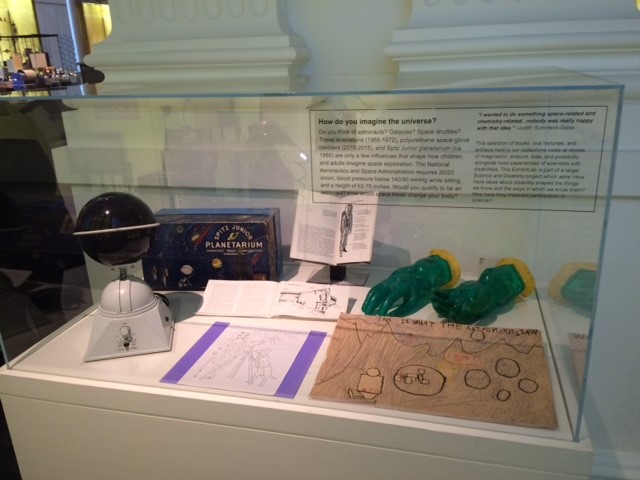

“How do you imagine the universe?” exhibition detail. Photo credit: Jessica Martucci (used with permission from the Science History Institute)

JM: The oral history project is the heart of this work, and I’ve loved every minute I’ve spent talking to the thirty-three (and counting) people who have shared their life stories with me.

Beyond oral history, our museum has been actively collecting objects that allow us to talk more directly about the intersection of the history of science and disability in our displays. This work led us to develop our current exhibition, Science and Disability, which draws on themes from the oral histories to interpret the objects on display. The four exhibit cases explore how disability intersects with science to shape our ideas about participation in science.

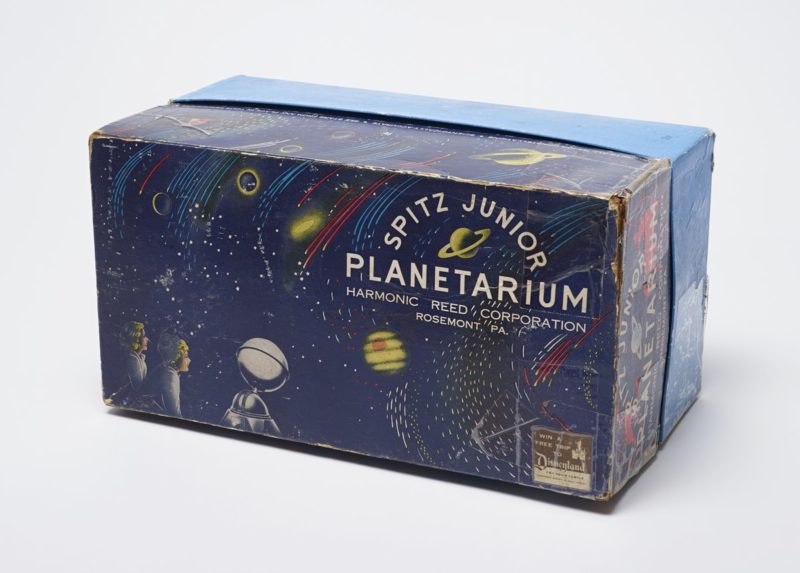

The Harmonic Reed Corporation’s Spitz Junior Planetarium, ca. 1955, Science History Institute, Philadelphia

The first case includes objects that speak to the ways that science is presented to children. Here, a late-twentieth-century space flight pamphlet geared towards children demonstrates how gendered and ableist assumptions are subtle but hegemonic. The second case is actually a captioned video and audio station that plays oral history excerpts that detail how these biases have shaped the lived experiences of people with disabilities who have pursued careers in science. A third case highlights the contributions made to modern scientific knowledge by individuals who have disabilities. The final case explores the more recent public activism and advocacy work by people with disabilities in STEM which has helped bring these stories to light.

NB: Did you have any preconceived notions or conclusions going into this project that have since been changed in the course of your research and outreach? If so, can you talk a little bit about that?

JM: One thing that I’ve found particularly noteworthy is the extent to which intersectionality shapes people’s experiences with disability. I think I went into this project assuming that generational differences (pre-Americans with Disabilities Act—ADA—and post-ADA, for example) would be the most important in terms of shaping how people experience disability in their careers. In reality, based on the interviews I’ve conducted, I have come to see how social and economic positions have consistently played a dominant role in shaping the lived experience of disability. I think that studying disability experiences in STEM makes other inequalities much more visible.

~Jessica Martucci earned her PhD in the history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania in 2011 and is the author of Back to the Breast: Natural Motherhood and Breastfeeding in America (University of Chicago Press, 2015). Her work on the Science History Institute’s Science and Disability Project is part of her broader interest in understanding the mechanisms and effects of exclusion and inclusion in the history of science and medicine.