The accidental web archive: The Tragedy at Virginia Tech Collection

14 March 2018 – Roger Christman

Editor’s note: This is the third post of a series that continues the conversation begun in the February 2018 issue of The Public Historian with the roundtable “Responding Rapidly to Our Communities.”

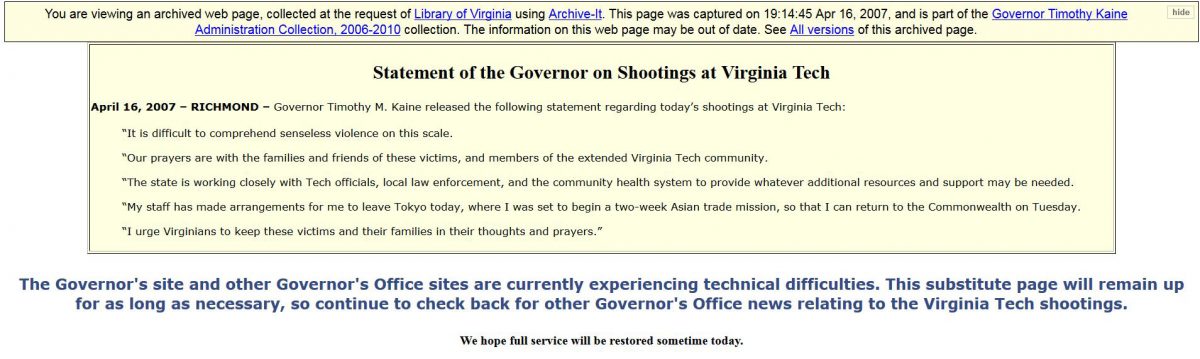

Screenshot from Virginia Tech website, April 17, 2007.

Eleven years ago, Seung Hui Cho killed thirty-two people and injured at least seventeen others before turning the gun on himself. At the time, the April 16, 2007, massacre at Virginia Tech was the deadliest shooting incident by a single gunman in US history. In 2007, I worked at the Library of Virginia as a state records archivist and managed the library’s budding web archiving program. In the immediate aftermath of the shooting, I quickly created a web archive collection, Tragedy at Virginia Tech, in order to capture how the Commonwealth of Virginia responded as recorded online. Tragedy at Virginia Tech is an early example of a rapid response collection and in hindsight provides some lessons learned for public historians when creating these type of collections.

In 2007, web archiving was in its infancy. Facebook and Twitter were relatively new and not widely used, especially by government. The Internet Archive’s subscription web archiving service, Archive-It, was less than two years old. The Library of Virginia became the first Archive-It partner in 2006 and I began managing the library’s web archiving program. It was primarily a solo venture; I was the library’s lone web archiving arranger. I wrote the collection development policy, selected the websites to archive, did most of the quality assurance on crawls, and attempted to describe each collection and website. As the state archives, the library collects the archival records of Virginia state government, and the library’s web archiving collection guidelines mirror those for the library’s physical collections. Records from the commonwealth’s public universities are outside the library’s collection scope. But the policy, adopted in March 2007, was also flexible, allowing the library, at its discretion, to crawl websites related to “significant public safety and health incidents or other noteworthy events.”

Tragedy at Virginia Tech did not start out as a rapid response collection. In fact, it was an accidental collection born in part by the technical limitations of Archive-It. One of the first web archive collections I created focused on the websites of the administration of Governor Tim Kaine. My initial reaction upon learning of the shooting at Virginia Tech was to crawl the governor’s website. Due to technical difficulties, the site was not working on April 16. A substitute page contained only Governor Kaine’s statement on the shooting and promised additional information when the main site was restored. By the next day, the governor’s website was back up and included a link to the Virginia Tech website, which contained news updates, messages to the Virginia Tech community, and podcasts of a press conference featuring Virginia Tech and state government officials. I quickly appraised these sites and decided to archive them. Even though the library does not collect the websites or records of Virginia’s colleges and universities, I felt this content was important to understand the Kaine administration’s response to the tragedy. This decision created a new set of challenges. Virginia Tech was adding new web content daily. How often should I capture each website? Virginia Tech was also creating new websites with content that was difficult to capture with Archive-It. How would I manage the capture? Should I add this material to the Kaine administration collection? Should I create a new collection? The quirks of Archive-It circa 2007 made the decision for me: I created a new collection.

Screenshot of Governor Kaine’s website, April 16, 2007.

In 2007, Archive-It only allowed partners to archive a maximum of three hundred “seeds”—URL access points—at one time across all collections. The links to the Virginia Tech content found on Governor Kaine’s website had a different web address than the seed (Governor Kaine’s website) and Archive-It would not capture them. The Virginia Tech website had a similar issue; audio and video files on the site had different URLs. The only way to ensure the “play back” of the website was to crawl each out-of-scope seed separately. Creating the Tragedy at Virginia Tech collection made it easier for me to manage and schedule crawls given. I am happy to report Archive-It 2017 no longer has such limits and it makes it much easier to capture out-of-scope content.

The library had no plan for the Virginia Tech collection. The content reflects what I thought was important and possible to crawl at the time: government and university sites about the shooting, victims, after action reviews, and events commemorating the shooting’s anniversary. It does not include memorial or tribute sites or media sites. It never occurred to me to collaborate with Virginia Tech on their April 16 Archive or to include other library staff members to assist me with site selection. This is not how a public historian would create a rapid response collection today. Diversity in setting the scope and selecting websites to include in a spontaneous collection should be a core requirement for two reasons. One, it is practical. One person cannot possibly know or have time to search for potential websites for a collection. Two, it may prevent individual bias from creeping into the collection. For example, many rapid response collections are created in the aftermath of mass shootings. Should your collection include content discussing gun control (both pro and con)? Having more people involved in the selection process, including the public via a website nomination process, can ensure that the collection reflects a diverse range of views even if you personally do not share them.

I remember creating the collection because of the “historic” nature of the shooting. I confess that I initially viewed that day’s events with the emotional detachment of an archivist/historian. But what made it “historic”? The number of people killed? The thirty-two people who died on April 16, 2007, are not numbers. They had names, families, hopes and dreams—a future. The biographies of the dead quickly shattered my impassiveness. What I saw as “historic” in 2007 is an ever-present tragedy for the families who lost their loved ones.

Public historians need to recognize that collecting materials related to a tragedy is emotional and can affect you in unexpected ways. It happened to me five years after I created the Tragedy at Virginia Tech web archive when I began to process the e-mail of the Kaine administration. In the aftermath of the shooting at Virginia Tech, Governor Kaine provided his personal e-mail address to family members of those killed or wounded. Over the next two years, Governor Kaine and his staff exchanged e-mails with family members in which they describe their grief, their anger, and their search for answers. These e-mails were transferred to the library at the end of the Kaine administration in 2010. They are some of the most powerful records I have encountered as an archivist. Reading the biographies of the dead in 2007 captured in the web archive made me sad. Reading some of these e-mails overwhelmed me with emotions of grief. For the first time in my career, I had to stop working on a collection and walk away. Why did the e-mail affect me differently than the websites? What changed in the intervening five years? I became a parent. The possible loss of a child to violence was now real to me. It also reminded me that it is okay to have this type of reaction. It is what makes us human. My advice: if possible, do not go it alone. When creating a rapid response collection, look for collaborators even if it is just to help keep you emotionally grounded.

~ Roger Christman is a senior state records archivist at the Library of Virginia.