Making meaning from ashes—the development of the Victorian Bushfires Collection

02 May 2018 – Liza Dale-Hallett

Editor’s note: This is the fifth post of a series that continues the conversation begun in the February 2018 issue of The Public Historian with the roundtable “Responding Rapidly to Our Communities.”

“CFA at the fire front,” Black Saturday Bushfires, Strathewen, Feb. 7, 2009. Photo credit: Museums Victoria

The Black Saturday Bushfires are the worst natural disaster in Australia’s recorded history.

One hundred and seventy-three people lost their lives on February 7, 2009. More than 300 died from the heatwave preceding the fires and unknown numbers have died subsequently. Another 414 people were injured. The fires destroyed or damaged over 3,400 properties, killed or injured over 11,000 farm animals, burned nearly 430,000 hectares of land across Victoria, killed unknown millions of wildlife, and directly impacted over one hundred communities. Nearly ten years later, people and communities are still living with the impacts of this disaster.

The Victorian Bushfires Collection began immediately following Black Saturday. It developed in direct response to an overwhelming call from individuals and communities across Victoria for their state museum to bear witness to this disaster. From the board level down, Museums Victoria committed fully to documenting this national tragedy. Anyone who was in Victoria on that day was seared by the day’s ferocity and the unfolding tragedy.

A quick survey of the museum’s collection indicated that this recurring theme of our history was significantly underrepresented. The first stages of the project focused on artifacts, images, and stories relating to the impact of the bushfires. This multidisciplinary collection, which now spans over one thousand items, documents bushfires across Victoria’s landscape, ecology, and history.

Museum Victoria’s well-established community partnerships provided a key foundation for the collecting process. While documenting natural disasters was a new endeavor, I had fifteen years’ experience in developing a number of contemporary collecting projects. The development of the Victorian Bushfires Collection drew on this experience and the extensive community networks established.

The Kinglake chimney was collected from the burnt remains of a home in Kinglake and was reinstated in the Forest Gallery at Melbourne Museum. Photo credit: Museums Victoria.

We encountered several inevitable challenges in documenting this disaster—time, resources, contaminated sites and artifacts, trauma, and stories reduced to ashes. Rescue collecting demands a dynamic and iterative approach. I needed to be fast, flexible, and very mobile. The museum also needed to be agile and innovative.

The largest and most challenging item collected was a chimney from Kinglake. Time was short: as home sites were cleared, chimneys were the first thing to be removed. By-passing the usual museum approval processes, senior managers quickly decided to facilitate this urgent acquisition. Collection managers and conservation staff had to develop new procedures for handling and storing these fragile and contaminated materials. Digital collecting and documentation suddenly became a major priority. The successful collection of the chimney also depended on the generosity, expertise, and equipment of local contractors.

Community and organizational partners were essential. We worked with the Country Fire Authority (CFA), Red Cross, Victorian government departments including the Bushfire Recovery Authority (established to respond to the disaster), Alfred Hospital Burns Unit, and local historical societies. We also collaborated with the National Museum of Australia to develop mutually reinforcing collections.

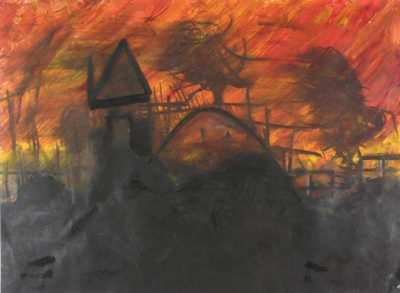

“Ashes” was created by Michael, a grade 6 student from Healesville Primary School. It is one of the forty works of art acquired by Museums Victoria. Image credit: Museums Victoria.

Creative outcomes and important community benefits emerged from these relationships. One partnership enabled an exhibition of artwork by students from Healesville Primary School at Melbourne Museum. The artworks provide an evocative and incredibly detailed account of the lived experiences of this community as seen and felt by these children. Forty of these works were subsequently acquired for the Victorian Bushfires Collection.

Many of the places I visited were sites of tragedy. I had to deal with fragile people whose lives had been shattered. Collecting stories of disaster involves tears, hugs, and bottomless cups of tea. A key challenge was how to balance my curatorial goals with the immediate capacities of the community contributors, while not causing more trauma or neglecting my own personal needs.

My first interview was with a former colleague. I interviewed Bill, in shock that he was still alive, his dream home in ashes, soon after Black Saturday, and then eighteen months later. Sharing his story was cathartic and assisted him in the slow process of recovery. Bill was relieved to know that I had my own care plan in order.

This mass of fused glass, ceramic and metal was found in the ruins of a home in Skyline Road, Yarra Glen, which was destroyed by fire on Black Saturday, Feb. 7, 2009. Photo credit: Museums Victoria.

Where lives have been lost or forever changed, or where precious belongings have been altered beyond all recognition, the intangible and symbolic become central. Video interviews gave form to the intangible, revealing the complexities of lived experience, enriching our understanding of existing collections, and filling significant gaps in material evidence. Many fire-affected artifacts became evocative symbols of the fragility of life, the depth of loss, the miracle of survival, and the transformative power of fire.

I interviewed over eighty people across Victoria; these are the key reasons they shared their stories with Museums Victoria:

- They felt that we were committed to the long term, unlike some of the recovery agencies and mass media.

- They wanted to tell their story in their own words, in their own way. We invited their active participation in interpretation, collection development, and storytelling.

- They hoped their stories would help others understand bushfires and be better prepared for the future. They appreciated our commitment to community education and engagement.

- Many had been traumatized by the inaccuracies of media reporting and confusing bureaucratic processes. We have a reputation for being independent, unbiased, and trustworthy.

Museums can play a unique role in the wake of disaster, including: demonstrating the power of stories for community healing and understanding; providing a place for reflection and commemoration; documenting the complexity and diversity of the lived experience of disaster; enriching understandings and broadening perspectives through cross-disciplinary and community partnerships; providing a historical and ecological context to understand disaster; using art to help people to engage with complex feelings and experiences; and contributing to the rebuilding of a sense of place and identity through public programs, exhibitions, and collections.

Since February 2009, Australia has experienced more “unprecedented” natural disasters. History shows that bushfires are a natural and essential feature of the ecosystem in southeast Australia, the most fire-prone place on earth. This sobering reality points to another important role for museums—to help communities remember and understand past disasters and use history as a tool in preparing for future disasters.

Mona Farr was born in 1909 and was featured in the media following Black Saturday, as a “triple-fire survivor” of three major bushfires: 1919, 1939, and 2009. Credit: Museums Victoria.

This final point leads me to Mona Farr’s story. Mona lived through the 1919 bushfires as a child of ten. While her parents were fighting the approaching flames with hessian bags, she huddled with her three younger siblings under the kitchen table, together with her two family dogs and a frightened wild fox. When she was in her late teens, Mona wrote a poem that captured the horror of this experience. In 2009 I recorded her reading this poem. Mona’s reading demonstrates the power of video, and her poem is a poignant reminder of why preserving and understanding the past is so important for our futures.

~ Liza Dale-Hallett is senior curator, Sustainable Futures, for Museums Victoria, Australia.