The role of curatorial work in our two pandemics part 2: Inside the gallery

28 April 2021 – Elena Gonzales

This is the second part of a two-part essay in which I propose five ideas for anti-racist museological work that carries a public health benefit. In Part 2 I looked at the context in which curatorial work takes place and how the institution can set the stage for effective curatorial work for social justice. I discussed the importance of protecting the staff and creating an anti-racist institutional culture. In what follows, I continue the article with three strategies for curatorial work.

Collaborate

Collaboration is crucial to anti-racist curatorial work and has been for as long as exhibitions have told cross-cultural histories. Now it is both crucial and popular. Some interesting resources have cropped up to help organizations without a robust history of inclusion or collaboration become more inclusive and open to sharing authority with stakeholders of all kinds. The toolkit—mentioned in Part 1—from Museums as a Site of Social Action (MASS Action) and my own book, Exhibitions for Social Justice, are two examples. Another is OF/BY/FOR ALL, the new project of Nina Simon, the former Director of the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History (MAH). Organizations can quickly assess themselves on the website and then use free tools or seek consulting services.

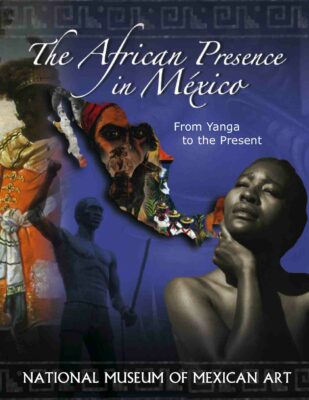

The cover of the catalog for African Presence in México. Chicago, IL: National Museum of Mexican Art, 2006.

In Exhibitions for Social Justice I wrote about another, much older project, The African Presence in México (2006-2011) by the National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA). The project included three exhibitions (two of which traveled for five years), an annual Afro-Mexican studies symposium, a K-12 curriculum, and a textbook-like catalogue that shares the anti-racist history the exhibitions told. (I curated one of the exhibitions: Who Are We Now? Roots, Resistance, and Recognition.)

African Presence was a collaboration between the (mostly Mexican) museum staff and Black leaders from across the cultural sector in Chicago. Two important lessons from the work of this steering committee still resonate today: respectfully engage partners in a project before it starts. Find out how the project meets each partner’s goals. And actually listen to partners and make changes accordingly. The NMMA did these things and is still reaping the benefits nearly a decade later.

Curate

Museums that represent communities of color have always sought some type of anti-racist curatorial work, some undoing of the harm to people of color that many predominantly white institutions (PWIs) have perpetrated and supported. A Declaration of Immigration (2008) is another example of an anti-racist exhibition from the NMMA. Xenophobia is racism too, and Declaration showcased another important strategy for anti-racist curatorial work: letting artists offer entry points into difficult topics. Americans (2018), from the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), uses questioning and beautiful design to draw visitors into topics that may have previously been invisible to them.

Welcome Blanket in July 2017. Image courtesy of the Smart Museum of Art.

But PWIs need to embrace and excel at anti-racist curatorial work, even as they learn from and respectfully acknowledge the work of people of color. This role is important for PWIs for two reasons: first, white supremacy is a white problem that white people must fix. Secondly, although demographics in the US are changing quickly, there is still a large white population in the US that many institutions of color may not reach. PWIs can help those visitors learn to become anti-racist. Curators can, once again, facilitate a shift in culture.

Some PWIs are already doing this work. The Smart Museum of Art is one example of a PWI that has worked against racism for years and is also exploring entry points into curatorial work relating to health, such as Take Care, about how we care for ourselves and each other. The Smart collaborated with Jayna Zweiman in 2017 to create Welcome Blanket, an anti-racist response to xenophobia and the tattered social fabric of the US.

Inspire Action by Visitors

Welcome Blanket opened with a nearly empty gallery and quickly filled over several months as Zweiman, founder of the Pussyhat Project, crowdsourced the knitting of lap blankets for new immigrants to the US. She sought to represent the entire nearly 2,000-mile-long US/Mexico border in the yards of yarn that comprised the blankets.

Welcome Blanket in December 2017. Image courtesy of the Smart Museum of Art.

Participants also submitted letters of welcome to the recipients of the blankets. The curatorial strategy featured numerous opportunities for visitors to participate. They could make blankets (fueling their desire to visit and see their own work on display). They could prepare incoming blankets for display during weekly unpacking parties. And, they could knit or share their own immigration stories in writing inside the gallery. It is also worth considering how visitors might take action after leaving the exhibition.

The roles of curators in our two pandemics are intertwined. As curators work against racism, one of the specific topics that they should address is the inequitable risk communities of color have faced from COVID-19. This leads into interlocking conversations about racist inequities in healthcare, labor, income, housing, and education, which curators should also enable, host, and elevate. Fitting these pieces together with collections and collaborators is where storytelling begins.