“A Plan of the Town of Newport in Rhode Island:” Mapping Religious Toleration

When many of us think about the past, we think about words. Words fill the diaries, newspapers, speeches, account books, government documents, and other items that we use to tell the story of the past. While some of us may think of words first, objects, architecture, and even the landscape are just as crucial to the historic record.

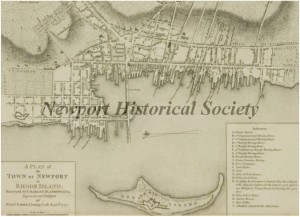

Maps fall somewhere in between as they are documents but they reflect the physical world and can tell us about the people who crafted the build environment. Let’s take a look at a map of colonial Newport, Rhode Island from the Newport Historical Society’s collection and see what it tells us about life in Newport in the 1770s and its history of religious toleration.[1]

Maps fall somewhere in between as they are documents but they reflect the physical world and can tell us about the people who crafted the build environment. Let’s take a look at a map of colonial Newport, Rhode Island from the Newport Historical Society’s collection and see what it tells us about life in Newport in the 1770s and its history of religious toleration.[1]

As part of the British army’s occupation of Newport from 1776 to 1779, Charles Blaskowitz surveyed the town and William Faden published the map in England in 1777.[2] The British occupation proved difficult for the people of Newport, many of whom left, and it took the town decades to rebuild its economy. Thus, this 1777 map captures Newport at its colonial peak. Through this map, we can see what the town looked like before the occupation took its toll.[3]

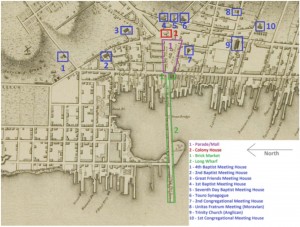

Newport, like the rest of colonial Rhode Island, was founded by religious dissidents. Men like Nicholas Easton, William Coddington, and John Clarke settled the town in 1639 and the Newport Compact, signed that same year, included commitments to religious liberty.[4] Religious liberty is easy enough to trace through the documentary record, but this map also shows these ideals. The 1777 map shows that ideas about religious toleration were quite literally built into the landscape of the town. I have edited the map to differentiate between the various sections of town.

The Parade or Mall is outlined in purple. This square was the heart of colonial Newport. The Colony House (noted in red) was built at the top of the Parade, and the Brick Market and Long Wharf (noted in green) were at the bottom. Built in 1739 to replace an early wood structure, the Colony House is an imposing brick building. It served as the heart of colonial politics in town. The Brick Market, constructed in 1762, is another impressive brick building that served as the economic center of the town. Merchants came in along Long Wharf and conducted their trade in the building. Thus, the heart of colonial Newport was flanked by politics and economics.

The Parade or Mall is outlined in purple. This square was the heart of colonial Newport. The Colony House (noted in red) was built at the top of the Parade, and the Brick Market and Long Wharf (noted in green) were at the bottom. Built in 1739 to replace an early wood structure, the Colony House is an imposing brick building. It served as the heart of colonial politics in town. The Brick Market, constructed in 1762, is another impressive brick building that served as the economic center of the town. Merchants came in along Long Wharf and conducted their trade in the building. Thus, the heart of colonial Newport was flanked by politics and economics.

At first, this may seem unremarkable. Politics and economics are important to any city, especially one as prominent as colonial Newport. However, when placed in the context of other colonial New England towns, the difference becomes clear. Many towns, especially in Massachusetts, featured churches at their center.[5] Placing the church in the center of town announced its importance to the community, and often its link to politics. Thus, by refraining from building a church on the Mall, colonial Newporters were making an important statement about the relationship between religion and government.

We need to be careful about what exactly this statement was, though. By refraining from placing a church in the square, the town founders were not stating that religion was unimportant. In fact, many of them were deeply religious. Rather, they believed that faith was too precious to be tainted by government, and did not want to favor any particular interpretation of religion over another.

The blue buildings on the map show where colonial Newporters worshipped. Even though a church was not on the Parade, colonial Newporters were not deprived of religious options. They had at least 10 different communities to chose from, and these communities represented a wide variety of traditions including Baptist, Seventh Day Baptist, Quaker, Congregationalist, Anglican, and Moravian faith traditions, as well as Judaism.

By looking at the blue buildings on the map, we can see that they form a ring around the Parade, and many are in places of importance on hills. With its cupola, the Friends Meeting House could easily be seen from the water. Trinity Church’s large steeple can be seen in many early images of the harbor. (Today, Trinity lies at the top of a grassy park called Queen Anne’s Square which looks misleadingly like a New England town green. However, buildings were torn down to create the park in the 1900s.) Touro Synagogue was prominently placed on a hill behind the Colony House.

Though all of these religious communities were welcome to move to Newport and build houses of worship, they were not all treated equally. Thus, the map has limits as an artifact; it cannot tell us details about the daily interactions of these various groups. However, it provides a starting point for beginning to understand how values relating to religion, politics, and economics impacted the city as colonial Newporters crafted a new community from the ground up.

~ Katie Garland

[1] For an introduction to religious toleration in early America, see: Chris Beneke, Beyond Toleration: The Religious Origins of American Pluralism. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008); Chris Beneke and Christopher S. Grenda, ed. The First Prejudice: Religious Tolerance and Intolerance in Early America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011).

[2] Newport Historical Society, Object Number 01.952, Charles Blaskowitz and William Faden, “Map,” 1777, http://newport.pastperfect-online.com/32053cgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=45E4C7DE-1AA9-44DD-9F86-343125991222;type=101.

[3] C.P.B. Jeffreys, Newport: A Concise History (Newport, RI: Newport Historical Society, 2008), 35-50.

[4] Ibid., 5-13.

[5] Joseph S. Wood, “Village and Community in Early Colonial New England,” Material Life in America, 1600-1860, ed. Robert Blair St. George (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988), 159-169; Robert J. Dinkin, “Seating the Meetinghouse in Early Massachusetts,” Material Life in America, 1600-1860, ed. Robert Blair St. George (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1988), 407-418.

If you haven’t come across it, you might be interested in looking at Steve Mrozowski’s MA thesis based on excavations of Queen Anne’s Square in the early 1980s. I know the thesis is on file at Brown, or you could contact him at U. Mass Boston ([email protected])

Found the reference I was thinking of and I even have a duplicate xerox I’ll bring to the meetings. It’s a bit dated, but offers an archaeologist’s thinking about the Newport landscape — Stephen A. Mrozowski, “Landscapes of Inequality” in The Archaeology of Inequality, edited by Randall H. McGuire and Robert Paynter (Blackwell, 1991), pp.79-101.

Hi Elizabeth,

Thanks for sending this my way! I have not read it yet, but the authors’ names sound vaguely familiar, so I look forward to checking it out. I do not know as much about the Queen Anne section of town as I would like to.

Interesting! I like how religious toleration can be read in space. Are the buildings still extant? Can you “read” them today?

Hi Suzanne,

Most of the buildings are still around! The Newport Historical Society owns or serves as a steward for a number of them – Great Friends Meetinghouse, Seventh Day Baptist Church, Colony House, and Brick Market – so the public can even get tours of them. And the streets are essentially in the same places as they used to be as well, which helps a lot when teaching people to read the landscape around them.