Memorial Paine’s everyday lives: Local stories with universal lessons

05 April 2012 – Zachary McKiernan

Letters from Chile, advocacy, social justice, public engagement, memory, museums, human rights, international, politics

Raúl Lazo liked to ride horses. Luis Gaete worked with his hands in the fields. Juan Leiva believed rural education was a right. José Castro had a red tractor. Juan Leonardo, president of the Association of the Relatives of the Disappeared and Executed Detainees of Paine (AFDD-Paine), explained on a sunny countryside morning that this was a principal point of Memorial Paine: to (re)humanize those community members who fell victim to Pinochet’s repression in the rural region for which the memorial is named. Reinaldo went on to say that family members’ participation was imperative to the memorial-making process, not only to establish a narrative that rescued the daily, lived experiences in rural Paine but to also create a culture of and respect for human rights through intergenerational and community dialogue. Thus, Memorial Paine now operates as a public space for reflection as much as a center for cultural and social activities aimed at life and human rights.

Raúl Lazo liked to ride horses. Luis Gaete worked with his hands in the fields. Juan Leiva believed rural education was a right. José Castro had a red tractor. Juan Leonardo, president of the Association of the Relatives of the Disappeared and Executed Detainees of Paine (AFDD-Paine), explained on a sunny countryside morning that this was a principal point of Memorial Paine: to (re)humanize those community members who fell victim to Pinochet’s repression in the rural region for which the memorial is named. Reinaldo went on to say that family members’ participation was imperative to the memorial-making process, not only to establish a narrative that rescued the daily, lived experiences in rural Paine but to also create a culture of and respect for human rights through intergenerational and community dialogue. Thus, Memorial Paine now operates as a public space for reflection as much as a center for cultural and social activities aimed at life and human rights.

When the world trained its eyes on Chile in the immediate aftermath of the 1973 military coup, the focus was on the epicenter: Santiago. But when Hunter Hawk jets and an array of army tanks were bombing the presidential palace La Moneda, so too were Chile’s less celebrated regions resisting and eventually falling to the new military order. In Paine, a small farming community about 20 miles south of Santiago, seventy people were killed and/or disappeared in October 1973, making it, according to Chile’s first truth commission, the area with the highest percentage of victims in relation to its population. In other words, “the entire community had been destroyed by terror and fear” (Paine: Un Lugar para la Memoria, AFDD brochure).

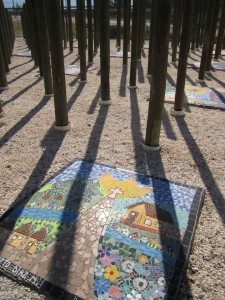

Terror and fear have been replaced with the “Memory of Life” at Memorial Paine. The memorial, initiated in 2000 and inaugurated in 2006, is uniquely local while its message undeniably universal. Situated on a small parcel surrounded by agricultural lands, the memorial’s aesthetic deliberately engages the rural environment and lifestyle. Approximately 1,000 erected wooden posts spaced a few meters apart, a forest of sorts, follow the contours of the Andean cordillera, the coastal mountain range, and the verdant valley between them. Of these, 70 posts are “missing” to represent the executed and disappeared. A small stream runs alongside the parceled property.

Terror and fear have been replaced with the “Memory of Life” at Memorial Paine. The memorial, initiated in 2000 and inaugurated in 2006, is uniquely local while its message undeniably universal. Situated on a small parcel surrounded by agricultural lands, the memorial’s aesthetic deliberately engages the rural environment and lifestyle. Approximately 1,000 erected wooden posts spaced a few meters apart, a forest of sorts, follow the contours of the Andean cordillera, the coastal mountain range, and the verdant valley between them. Of these, 70 posts are “missing” to represent the executed and disappeared. A small stream runs alongside the parceled property.

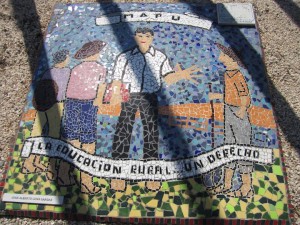

Most striking, though, are the seventy mosaics that fill the forest’s gaps: the epicenters, if you will, of the memorial, showing the daily life and likes of Paine’s persecuted before the persecution began. Raul Lazo with his horses. Luis Gaete in his garden and fields. Juan Lieva armed with textbooks and lectures. José Casto’s red tractor. These mosaics are the work of family members and community friends, working along artists, social workers, and psychologists, that glued together the memorial’s goals: the participation of family members and the creation of, no doubt, creative dialogue and a culture of human rights for the community. The mosaics serve as markers of a past that is sometimes silent at other human rights memorials: Paine’s citizens as humans, neither victims nor martyrs. And their their construction also produced new and old narratives between neighbors.

Most striking, though, are the seventy mosaics that fill the forest’s gaps: the epicenters, if you will, of the memorial, showing the daily life and likes of Paine’s persecuted before the persecution began. Raul Lazo with his horses. Luis Gaete in his garden and fields. Juan Lieva armed with textbooks and lectures. José Casto’s red tractor. These mosaics are the work of family members and community friends, working along artists, social workers, and psychologists, that glued together the memorial’s goals: the participation of family members and the creation of, no doubt, creative dialogue and a culture of human rights for the community. The mosaics serve as markers of a past that is sometimes silent at other human rights memorials: Paine’s citizens as humans, neither victims nor martyrs. And their their construction also produced new and old narratives between neighbors.

Juan Rene, whose grandfather was disappeared in Paine on October 16, 1973, likes history. He began his participation by making a mosaic and attending the memorial’s social and cultural events. But he went beyond this in the form of his thesis “Encounter with Life and Death: History and Memories of State Terrorism and Violence in Paine (1960-2008)” at the University of Chile. Although this work isn’t displayed at Memorial Paine, it is an important piece of the puzzle. It is at the same time both a producer and product of the Memorial Paine in that it sprung from and developed alongside it. The work opens up a larger historical analysis that captures the present moment as much as the local precedents that led to the repression during and even after the dictatorship. It is a rural history that was written from a social-cultural perspective because of the memorial made some three decades after the disappearance of his grandfather. This, I think, lends legitimacy to the potential of public memorials to move beyond “soft culture” and into the sphere of both serious community activism and academic work.

Juan Rene, his uncle Juan Reinaldo (AFDD-Paine’s president), and others have achieved a unique experience in Paine: an activated memorial site outside of the traditional center of Santiago. Rescuing, retelling, and revalorizing the daily experiences—as much as the political and social paradigms—of Chile’s less celebrated rural communities is a work that uncovers silences; silences that however geographically peripheral stand central to larger lessons of resistance, repression, and respect for human rights. And if we listen to these silences, we no doubt will recognize and give life to the mosaic-shards that make up our own fragile memories.

Juan Rene, his uncle Juan Reinaldo (AFDD-Paine’s president), and others have achieved a unique experience in Paine: an activated memorial site outside of the traditional center of Santiago. Rescuing, retelling, and revalorizing the daily experiences—as much as the political and social paradigms—of Chile’s less celebrated rural communities is a work that uncovers silences; silences that however geographically peripheral stand central to larger lessons of resistance, repression, and respect for human rights. And if we listen to these silences, we no doubt will recognize and give life to the mosaic-shards that make up our own fragile memories.

~ Zachary McKiernan

This is Part 3 of the “Letters from Chile.” Also see the Introduction, Part 1, and Part 2.

Inspiring work.