Perspectives on a Changing Field: Part II

29 September 2020 – Daniel Vivian

Editors’ Note: This is the fourth of five posts summarizing the findings of the Joint Task Force on Public History Education and Employment, an initiative launched in 2014 to study trends in public history education and employment.

What Gets Students Jobs?

Experienced public history educators have long recognized that a degree alone is inadequate preparation for the public history job market. The applied dimensions of public history practice and the emphasis employers generally place on practical skills mean that classroom instruction is only part of what students should expect from their graduate program. The opportunities students have to gain practical experience and the choices they make during graduate school have a significant bearing on post-graduate outcomes. As the task force observed in its report on the survey of public history employers, “The survey data affirm guidance that public history educators and professionals have long touted. Experience matters. Getting as much as possible through applied assistantships, internships, volunteering, and employment is essential. Breadth and diversity of experience is equally important. Employers prize versatility, adaptability, and knowledge of multiple types of historical practice.”

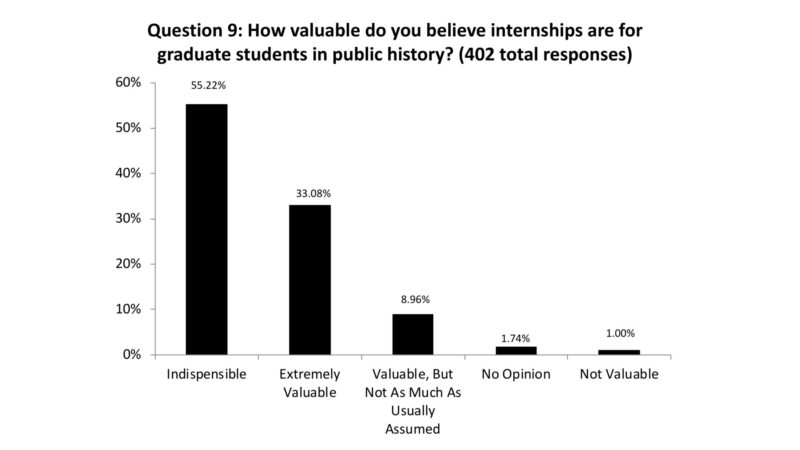

These points are well illustrated by the importance employers assign to internships. The employer survey found that 55 percent of respondents rated internships as an “indispensable” part of graduate education, and 33 percent rated them as “extremely valuable.” Nine percent categorized internships as “valuable, but not as much as usually assumed,” and one percent rated them “not valuable.”

Public history employers consider internships a crucial part of graduate education. The task force recommends that public history educators ensure that students have opportunities for one or more high-quality internships during their graduate studies. The NCPH best practices document on internships offers excellent guidance on the subject.

Based on these findings, the task force stressed the importance of providing graduate students with opportunities for high-quality internships. Ideally, an internship should provide substantial experience in one or more areas of historical practice; opportunities to develop marketable, readily transferable skills; opportunities to exercise independent judgment in developing historical programs or materials; and extensive interaction with experienced professionals. Internships should also be paid, a position the NCPH has advocated for since 2008. The NCPH best practices document on internships provides additional guidance. [1]

The proliferation of public history programs has not changed a basic maxim of public history: the field is competitive, and job-seekers who get good experience early in their careers generally do better than those who do not. Internships, volunteering, and paid employment all count.

Advocating for History

Many of the comments from survey respondents addressed subjects that lay outside the focus of the two surveys and the goals of the task force. Some concerned the effects of decreasing public support for historical programs and the many challenges facing history museums and historic sites. Others mentioned changing demographics, shifting audience interests, and the difficulties of capturing audience attention in an age of digital saturation. Meanwhile, others mentioned the influence of conservative politics, anti-intellectualism, and disdain for information at odds with celebratory narratives of American progress.

The task force’s investigations overlapped with a discouraging announcement: history majors reached a new low in 2017. As part of a long-term decline that has also affected fields such as political science, anthropology, and sociology, history majors now account for 5.3 percent of bachelor’s degrees awarded in the United States, below disciplines such as English, philosophy, anthropology, and religion.[2] The reasons for the decline are complex and continue to be debated, and how departments should respond differs depending on individual circumstances. Nonetheless, it is impossible to view this statistic without sensing that appreciation for history and its role in liberal democracies is at a low ebb.

The task force strongly believes that greater advocacy for history—with the public, with politicians, and within the academy—should be a priority for all historians, regardless of specialization or employment status. Disregard for history and the work of trained historians threatens history education, all forms of public history, and leaves the public ill-equipped to meet the challenges facing the nation and the world. Now more than ever, historians cannot afford to remain silent. The threats facing liberal democracies and human society in general demand informed perspectives on contemporary problems and the ability to envision more just alternatives. Although public historians routinely encounter inspiring, exciting examples of grassroots interest in history and activism related to historical subjects, long-term trends in public funding and support for education (K-12 and at colleges and universities), arts and humanities programs, museums, and archives are deeply troubling.[3]

The accomplishments of the task force, then, should be seen as not simply an inward-looking view of conditions in a particular segment of the field. They report on developments that should concern all historians and bear on the overall health of the historical profession. It is difficult to envision circumstances that would allow college- and university-level history education to thrive without a robust public history sector. Further, the influence many academic historians wish to have with general audiences relies partly on the varied forms of engagement public historians have helped pioneer and now employ in myriad settings. Along with such important projects as the American Historical Association’s Career Diversity for Historians initiative and the History Relevance Campaign, the task force’s findings suggest the importance of strengthening history education and advocacy with a long-term view of the field in mind.[4]

~Daniel Vivian is an associate professor and chair of the Department of Historic Preservation at the University of Kentucky. He has served as co-chair of the Joint Task Force on Public History Education and Employment since 2014.

[1] See also Meghan Hillman, “On Unpaid Internships, Professional Ethics Standards, and the NCPH Jobs Page,” History@Work, September 4, 2017.

[2] Benjamin Schmidt, “The History BA Since the Great Recession,” Perspectives on History 56, no. 9 (December 2018).

[3]The views of the task force on these subjects are based not only the comments of survey respondents but the collective experience of the group, which includes the current executive directors of the American Association for State and Local History, the American Historical Association, and the NCPH; two past presidents of the NCPH; and several experienced public history educators and practitioners.

[4] For more on the History Relevance Campaign, see Tim Grove, “What is the ‘History Relevance Campaign’?” History@ Work, Oct. 25, 2013.