The Atlanta BeltLine: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

23 January 2020 – Adina Langer

local history, Atlanta Series 2020, digital history, education, government, gentrification, race, urban history, 2020 annual meeting

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of posts from members of the Local Arrangements Committee for the NCPH 2020 annual meeting which will take place from March 18th through March 21st in Atlanta, Georgia.

Atlanta BeltLine passing Through Ardmore Park In northwest Atlanta, 2017. Photo credit: PghPhxNfk License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Like many sunbelt cities, Atlanta’s origins are more engineered than organic. And yet, we speak of cities in terms of “growth,” and Atlanta is no exception. Originally called “Terminus,” the city was founded at the southern terminal of the Western and Atlantic Railroad in 1837 on land that had been historically occupied by people of the Muscogee (Creek) and Cherokee nations. Their forced removal had been authorized just seven years earlier by Congress via the Indian Removal Act of 1830. In 1845, the Georgia Railroad connected the city from Madison, Georgia to the “West End” neighborhood. In 1846, The Macon and Western Railroad came up from the South. And in 1870, the West Point and Atlanta Railroad terminated just west of the city in East Point. Between 1871 and 1908, a wheel of railroads would grow to surround the city center, connecting points on these railroad “spokes.” The result would be what is now referred to as the “beltline.”

Exhibit graphic from “Georgia Goes to War” at the Museum of History and Holocaust Education. Design by Zoila Torres. Photo credit: Adina Langer

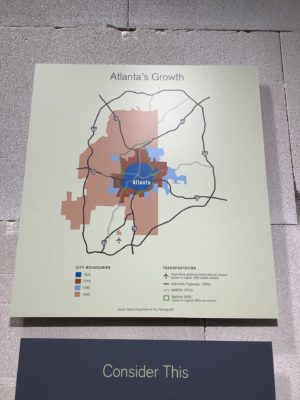

When we opened a section of our Georgia Goes to War exhibit that focused on Atlanta in 2017, we included a chart of the city’s growth. In it, transportation routes appear like the rings of a tree, with the 1900 heart of the city growing to meet the beltline in 1918, inching outward in 1945, and then exploding asymmetrically westward in 1963 as the “perimeter” of the interstate highway system encircled the city once again.

Thirty years later, a Georgia Tech urban planning student named Ryan Gravel surveyed a city divided by highways and the legacy of segregation. Now, instead of serving as a borderline, the remains of the original rail corridor carried the potential to link together the city’s oldest neighborhoods. Gravel turned his vision for a mixed pedestrian/cyclist/transit trail flanked by parks, new developments, and affordable workforce housing into his 1999 masters thesis. And, unlike many ideas originated in masters theses, Gravel’s began the journey toward a kind of reality in the form of the Atlanta BeltLine.

After a 2003 feasibility report gained Atlanta City Council approval, and the nonprofit Atlanta BeltLine Partnership was founded in 2005, a continuous dance between private fundraising, government grants, voluntary tax allocations, corridor purchases, trail construction, public relations campaigns, park development, art displays, transit planning, private development, and more public relations campaigns has propelled the project forward. The Great Recession challenged the project’s initial funding model based on current taxes and future development, but the project was able to weather the storm. Affordable housing has proven to be the trickiest aspect of the project’s original vision to maintain, especially as the BeltLine’s popularity has driven new development and rising property values accompanied by the tax increases and potential for displacement that blurs the borders between redevelopment and gentrification. In fact, dissatisfaction with the project’s commitment to affordable housing and inclusivity led Ryan Gravel to leave the BeltLine organization in 2016.

Like many city planning projects, the public literature of the BeltLine is relentlessly forward-looking (although they do offer a document library going back to 2008). Yet, the project’s roots are intertwined with historic infrastructure and the narrative threads that run through Atlanta’s history. Adaptive use implies the revelation (and re-vitalization) of layers hidden beneath the palimpsest of the city. To that end, historic preservation and public history students in Atlanta have been involved in revealing and interpreting historical assets along the beltline since the inception of the project. The first report on the history of the Atlanta BeltLine and its associated historic resources was commissioned by the BeltLine Partnership and prepared by students in the Heritage Preservation Program at Georgia State University in the Spring of 2006. Nine years later, I taught a digital history course at GSU in which students further researched assets (and stories) along the beltline. The result was the Atlanta Rail Corridor Archive, an Omeka-based site that combines selected archival materials and narrative exhibits. Representatives of the BeltLine Partnership were there when my students presented their work.

The author standing on the Beltline beneath the Freedom Parkway overpass, February 2015. Photo credit: Georgia State University

March is springtime in Atlanta, so you should have opportunities to explore the BeltLine in lighter clothing that I’m wearing in this picture if you join us for the 2020 NCPH Annual Meeting. As you walk or bike along the trails, weaving between dogs on leashes and children decidedly off of them, think about the people who bring their energy to a city and what they do to make it grow. What links us together and what sets us apart? Which borderlines are engineered, and which emerge organically? Join me for an ice cream, or some dumplings, and let’s chat!

~Adina Langer has served as the curator of the Museum of History and Holocaust Education at Kennesaw State University since 2015. You can follow her on Twitter @artiflection.

What an informative article! I only heard of the Beltway when home for Christmas (2019) and was amazed at what a logical, useful path it is. Our granddaughter is now a freshman at KSU and loving it. I hope she will have a chance to meet you. :-). Thanks for sharing your infinite knowledge of this new Atlanta phenomenon.

Thank you, Susan. I’d be happy to meet you granddaughter and show her around the MHHE. Feel free to send me an email to discuss. Warmly, Adina.