Bachelor Girls or Perverts?: Teaching Histories of Sexuality in Public History Courses

16 May 2017 – Jordan Biro Walters

In her 1903 work Social Culture, Annie Randall White encouraged unmarried women over the age of thirty to form domestic partnerships with each other: “Many of our ‘bachelor girls’ live together and are the happiest people imaginable.” [1]

Annie Randall White, Social Culture: An Up-to-Date Book for Polite Society, Containing Rules for Conduct in Public, Social and Private Life, at Home and Abroad [S.l: s.n.], 1903, Josephine Long Wishart Collection: Mother, Home, and Heaven, Special Collections Library, The College of Wooster, Wooster, Ohio.

During the Progressive Era, etiquette and health writers such as Wood-Allen began to target loving, passionate, and physically affectionate same-sex relationships—known as romantic friendships—for public condemnation. Increased public recognition of lesbian sexuality threw suspicion on romantic friendships. A. Maude Royden posed the question in her own book Sex & Common Sense (1922): when does a friendship become too “absorbing?” Royden writes, “When you have the temperament of one sex in the body of another this cannot be. There is at once a disharmony, a dislocation, a disorder—in fact, a less perfect not a more perfect type . . . This is not progress but perversion.”[3] In the span of twenty years, etiquette authors moved from a positive framing of female companionship to classifying them as perverse.

These excerpts stem from a student-curated exhibition on gender and sexual norms of the Progressive Era. Students in my course, The Craft of Public History: Putting History to Work in the Real World, analyzed popular advice literature primarily aimed at women. The monographs are part of the Josephine Long Wishart Collection–Mother, Home, and Heaven (MHH), which is housed at the College of Wooster Archives in Wooster, Ohio. I selected MHH as a source base for the creation of undergraduate-curated digital exhibitions in order to help students practice interpreting themes of gender and sexuality for a public audience.

The project, designed for an introduction to public history course capped at twenty, exposed students to fieldwork in public history and the constructive possibilities of focusing upon gender and sexuality. With the National Park Service’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Heritage Initiative and publications such as Susan Ferentinos’s Interpreting LGBT History at Museums and Historic Sites, public history has begun to embrace representations of sexualities. My course provides an opportunity to train a new generation of public historians on how they might document sexual pasts. My own training as both a public historian and a scholar of LGBT history propelled me to bring these two disciplines into conversation with one another.

Course Goals and Process

I envisioned several goals for this course. First, I aimed to teach students how to become comfortable discussing gender and sexuality in a public online forum. I also hoped to help them dissolve the boundaries between the public rules of respectability and private lives. Lastly, I envisioned students uncovering and narrating queer experiences where they might be hidden in plain sight: within the pages of heteronormative advice manuals.[4]

The first component of the project required students to conduct research. I designated student archive workdays to analyze texts written by medical professionals and non-professionals for a white, middle-class audience. At first glance, a curator might use such texts to narrate the history of morals and manners of families in America. Reviewing code of conduct books with a new interpretive model—one that moves beyond a heterosexual trope—reveals different possibilities. For example, White’s reference to “bachelor girls” became a window in which to explore queer lifestyles.

Students in Biro Walter’s Public History class learning exhibition design at the May 4 Visitors Center, Kent State University, 29 October 2016. Photo by author.

After researching, the class discussed the implications of interrogating sources. In thinking beyond the norms presented in advice manuals, one student asked, “Are ‘bachelor girls’ really lesbians?” One interpretive challenge public historians face is the problem of ahistoricity when applying the term “lesbian” to a coded term such as “bachelor girls.” Scholars largely agree that by the twentieth century, queer historical subjects identified themselves by sexual orientation, including the use of the term lesbian. While not all unmarried women who lived together were lesbian couples, some engaged in same-sex relationships. The class concluded that curators should construct narratives that honor how “individuals self-identified at the time.”

Building the Exhibition

During the next phase, students divided into five groups and submitted exhibition proposals. I advised each group on how to narrow their focus and helped edit their working bibliographies. Next, students underwent training in Dublin Core metadata standards, learned best practices for online collections, and visited museum exhibitions.[5]

Individually students completed two assignments–an object evaluation and narrative history essay. Each group then wove these assignments into a draft of their museum script and built their exhibits on Omeka.net.

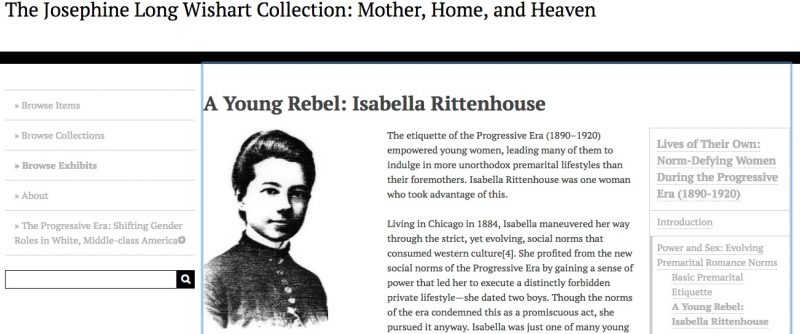

Exhibition page for Biro Walter’s student-curated project, “Lives of Their Own: Norm-Defying Women During the Progressive Era (1890–1920).” Photo by author.

The groups diverged in their final exhibitions. One devised an exhibit on women and beauty, another on gender roles. Two groups incorporated sexuality with an exhibition on sex education and another on ways women defied sex norms. For example, students applied a non-normative sexual interpretive framework to explore how three women, Isabella Rittenhouse, Jane Addams and Kate Sanborn, broke gender expectations in their intimate lives. This virtual exhibition, entitled Lives of Their Own: Norm-Defying Women During the Progressive Era (1890–1920), pairs etiquette book advice with lived experience to profile Rittenhouse’s heterosexual explorations outside of marriage, Addam’s same-sex intimacies, and Sandborn’s choice to remain unmarried.

Concluding Thoughts

While students succeeded in incorporating the history of women and gender and to some extent sexuality in their exhibitions, they missed opportunities to fill in other silences—that of race and class. Additionally, only half of the class achieved my third course objective: uncovering queer narratives. Too much flexibility in topic choice resulted in some students shying away from discussing sex, allowed others to avoid doing additional research and reading against the grain of primary documents.

The next time I teach this class, I will have students create a single exhibition and have each group work on a part of it, to better facilitate employing an intersectional approach. Nonetheless, students praised the hands-on experience they received as well as the opportunity to engage audiences in histories of gender and sexuality. Both the MHH collection and the student-curated exhibitions function as places of public dialogue on the history of gender and sexuality in America. Moreover, the project prompted library staff to begin digitizing selections from MHH. This digitization will start in Summer 2017 and be accessible through The College of Wooster’s Special Collections page in Open Works.

Collectively, students discovered the difficulty in uncovering sexual histories and began to understand why some historical narratives are more visible than others, a challenge public historians face with marginalized communities. Even if visible only in fragments, exploring queer historical representations results in an enriched understanding of the past. Audiences often know little about the historic lives of LGBTQ individuals, given that this history is absent from primary and secondary education and only sometimes offered at the university level. The tide has shifted toward recognizing and valuing LGBTQ history at historic sites, so the time is ripe to arm up-and-coming and veteran public historians with the tools to explore how the LGBTQ community has historically experienced and contributed to American society.

~Jordan Biro Walters is a visiting assistant professor of history at the College of Wooster. Her student’s exhibitions can be found here. Dr. Biro Walters can be reached at [email protected]

Citations

[1] Annie Randall White, Social Culture: An Up-to-Date Book for Polite Society, Containing Rules for Conduct in Public, Social and Private Life, at Home and Abroad [S.l: s.n.], 1903, p. 122, MHH Collection.

[2] Mary Wood-Allen, What a Young Girl Ought to Know, New rev. ed., Self and Sex Series (Philadelphia: Vir Pub. Co., 1905), p.154 and 155, Josephine Long Wishart Collection: Mother, Home, and Heaven, Special Collections Library, The College of Wooster, Wooster, Ohio. (Hereafter MHH Collection)

[4] I employ a very broad definition of queer—sexual and gender expression outside of societal norms.

[5] I would like to thank Digital Curation Librarian Catie Newton who gave a guest lecture on Dublin Core metadata standards and Special Collections Librarian Denise Monbarren for her hands-on archival sessions. College of Wooster alumni Kenneth M. Libben, curator of the Cleo Redd Fisher Museum, and Brett Hall, a staff member of the Harding Home Presidential Site, both gave presentations on best practices for exhibition design and writing.

What a well conceived project Jordan. Thanks for sharing!