Beyond descendant outreach: authentic engagement through increased accessibility in the Kith + Kin project

25 April 2024 – Emily Cadmus

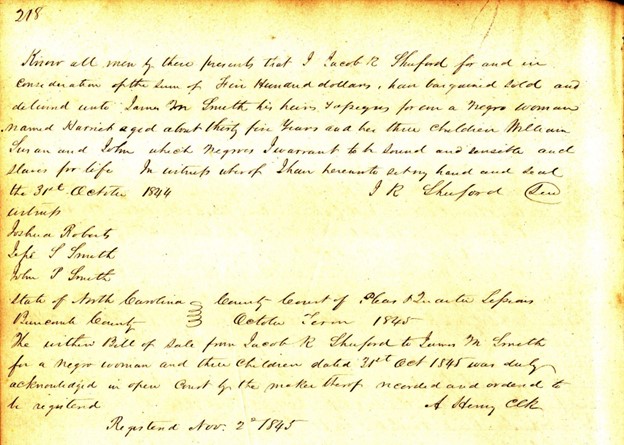

This slave deed shows the sale of a 35-year-old woman named Harriett and her three children William, Susan, and John. From this deed we learn the names of four enslaved people, as well as their presumed biological kinship to one another, which are details not typically included in most slave enumerations. Courtesy of the Buncombe County Register of Deeds, Book 23, page 218.

The past decade has seen big shifts in the interpretation of slavery and enslaved people. Descendant engagement has become a standard of practice at places like Montpelier, the Whitney Plantation, and the University of Virginia. Other institutions, like Duke University and Clemson University, have established archival collections centered on documenting enslaved people. Organizations, like the Georgetown Slavery Archive prioritize accessibility to their collections through digitization. These varied approaches all redress archaic methodologies. However, inequity and objectification still linger among some of our best efforts at amelioration. “The Kith + Kin Project” aims to address this problem.

Descendant engagement often happens on institutionally-defined terms, and many collections remain difficult to access. Organizations often fail to facilitate the most common way descendants choose to engage with the past: genealogical research. When genealogical research is performed about free people, descendant engagement is implicit. There is no need for outreach because the information is available for direct use by descendants in the ways that they desire.

The first major effort at establishing a large and public archive about slavery in the Americas is SlaveVoyages, which launched as an open-source database in 2008. While SlaveVoyages has been a paradigm-shifting resource, it relies on ledgers that offer little information about individual enslaved people. Researchers of African American history and American slavery are well acquainted with archival material such as estate accounts, letters, diaries, and deeds that sometimes contain more extensive descriptions of enslaved individuals. They can include physical descriptions, things an enslaved person may have said or done, a specific occupation, or notable events like pregnancy, illness, or injury in addition to kinships.

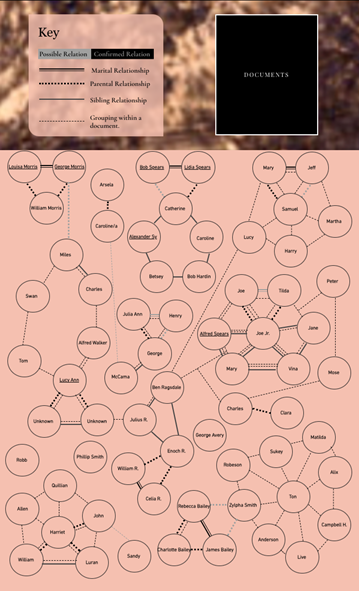

This Kinship Web shows definitive and potential relationships between people enslaved by the Smith/McDowell family in Asheville, North Carolina. It shows marital, parental, and sibling relationships, as well as groups of people who were sold, bought, or inherited together. Screenshot courtesy of Emily Cadmus.

As part of my graduate thesis, I built a website using this scattered archive of manuscripts and deeds to show kinship networks within a community of seventy-seven individuals who were enslaved by the same family at some point in their lives. This arduous process required access to multiple archives, transcribing handwritten documents, and creating several spreadsheets. I could not help but compare this experience with the ease I had researching the lineage of their enslavers. This archival inequity is the gatekeeper to knowledge about our ancestors, which is perhaps the most palpable way people can connect with history.

The extra labor demanded by this archival inequity kept my research bound to a site-specific interpretation. As victims of human trafficking, enslaved people were inherently mobile. By centering collections and exhibits on a site or enslaver, we are viewing enslaved people through the lens of their captivity. To disrupt impactfully the perpetuation of exploitation in the study of slavery, historians cannot rely on the constructs on enslavement to offer a holistic picture of the experience of an enslaved person. I am currently pursuing the development of a platform that facilitates researching the scattered archive through the digitization of multiple collections. The Interpreting Slavery Rubric, developed at The National Summit on Teaching Slavery in 2018, describes the scattered archive as having the “potential to create impactful and thought-provoking interpretation, yet institutions have allowed them to remain buried beneath the ground of the past, choosing to provide the public instead with partial truths.”

Partial truths are the result of an inadequate commitment to shared authority and truth-telling in descendant engagement. This interpretive approach is used by many Indigenous communities as well as scholars like Amy Lonetree and Henry Reynolds. While this practice is often associated with Indigenous histories, it also applies to the history of slavery. “Failing to tell the truth about race and slavery results in widely-held fears of engaging with people who look, speak, act, or think differently than oneself. It is lived out in anger and despair in feeling marginalized, erased, and invisible due to demographics or identity. It is experienced in the harmful effects of racism on the public’s physical, mental, and spiritual health.” (Interpreting Slavery Rubric, 2)

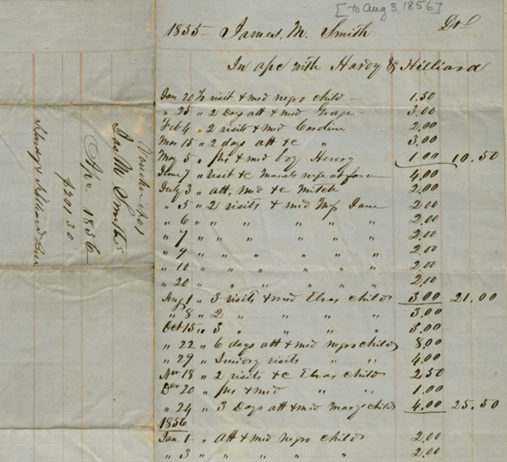

This ledger has information about medical care received by enslaved people. By itself, the document offers little specific information. Contextualizing this document with other records allows for the potential to identify individuals, clarify the timeline of an enslaved person’s life, or enrich a biographical profile of an individual. James M. Smith, medical ledger 1855-6, William Wallis McDowell Papers, Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill. Courtesy of Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

Shared authority is the essential function by which truth-telling can occur, and it begins by acknowledging that historians do not determine the truth. “Shared authority practices act as a corrective to previous patterns, and address intersections of erasures, recovery, and descendant community engagement.” (“Black is not the Absence of Light: Restoring Black Visibility to Digital Humanities” by Nishani Frazier, Christy Hyman, and Hilary Green) When archives are hard to access and use, or are limited by site, historians are obstructing shared authority and adhering to antiquated systems of power and oppression.

A public-facing digital collection of documents from multiple repositories can help to facilitate a more equitable methodology in the research of enslaved people. This project is still in the research and development stage. In order to see these ideas materialize, I need input, collaboration, and participation from a wide variety of stakeholders. As part of this group, I ask the broader community of history professionals to contribute to this survey. Your knowledge and expertise are critical to the development of something useful and beneficial for everyone.

~Emily Cadmus is a historian in Asheville, North Carolina. She completed her undergraduate degree in History from the University of North Carolina, Asheville in 2021. She received her MA in Public History from Western Carolina University in the summer of 2023. Her primary area of study is in slavery and emancipation in southern Appalachia.