Embodying the archive (Part 1): Art practice, queer politics, public history

05 April 2013 – Julia Brock

human rights, gender/sexuality, projects, advocacy, art, social justice, public engagement, community history, memory, archives

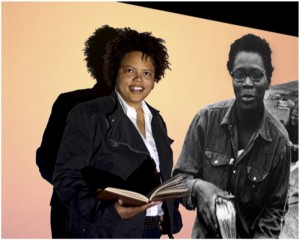

E.G. Crichton’s “Lineage: Matchmaking in the Archives” project connected living people with archival partners. Here, Elisa Parry with Pat Parker. Portrait by and courtesy of E.G. Crichton.

“All we have to open the past are our five senses. And memory.”

We public historians are increasing our fluency in languages. We are conversing with colleagues across the globe and across disciplines, we are ever dexterous in our work with new media, and we are constantly strengthening the ways we reach out to audiences, drawing from a language of engagement that has emerged since our field’s early days and that has blossomed in the last ten years. This emergent patois has meant more and different kinds of collaboration and models of practice, including institutional and individual partnerships with artists.

Alliances between public historians and artists are not new but are growing. Museums and archives have been inviting artists to reimagine their collections and broaden their public reach since at least the mid-1990s. As Laura Koloski argued in her recent case study of the artist-in-residency program at the American Philosophical Society Museum, there should be a development of shared language between collaborators concurrent with the rise in artist/historian partnerships.[1] In working with artists, we might begin to articulate a contemporary aesthetic of historical knowledge. How do we (and audiences) make sense of and draw conclusions about the past when it is represented in contemporary art practice or embodied by artistic performance?

Though, as Cathy Stanton has argued, we need to think critically about aestheticizing the past, artists add new dimensions to our language of engagement.[2] Contemporary artwork gives the past an affective power and can be a method of transmission that is sensory, critical, and non-rote. I was thinking of these possibilities when I learned of the work of John Q, an art and idea collective whose members are based in Atlanta and Virginia, and E.G. Crichton, the first artist-in-residence at the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco. As an attempt to continue a broader conversation about the relationship between art and public history practices, I interviewed Crichton and members of John Q, who have collaborated on projects together, via email. The edited interviews will be posted as a two-part series, foregrounding the voices of artists who reclaim queer histories through archival, performative, and process-oriented work.

John Q’s work engages queer history and politics and also the process of making the archives public. In 2010, John Q created a series of public performances called Memory Flash that were based on oral histories with gay Atlantans of the pre-Stonewall era. In the following Q&A, Wesley Chenault, Andy Ditzler, and Joey Orr reflect on embodied memory work, audience negotiation and participatory culture, and the relationship of archival preservation and cultural production. Interlaced with the text are images, sound, and video representations of the collective and their work. John Q’s upcoming project, The Campaign for Atlanta, addresses issues of queer migration using the space of Atlanta’s historic Cyclorama. In the fall of 2014, John Q will be providing work as part of a group show at the Zuckerman Museum of Art (ZMA), Kennesaw State University. As part of our ongoing conversations about collaboration and memory, the ZMA is producing a catalogue that will capture the collective’s work and put it in an expanded scholarly context.

The full transcript of the JohnQ interview can be found here.

The second post in this two-part series, linking to an interview with E.G. Crichton, will follow next week.

~ Julia Brock is Director of Interpretation for the Department of Museums, Archives, and Rare Books and is curator at the Museum of History and Holocaust Education, Kennesaw State University (near Atlanta, Georgia). She received her Ph.D. in Public History from the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 2012.

[1] See Koloski’s chapter, “Embracing the Unexpected: Artists in Residence at the American Philosophical Society,” in Letting Go? Sharing Authority in a User-Generated World, eds. Bill Adair, Benjamin Filene, and Laura Koloski (Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, 2011). Thanks to Lisa Junkin for this and other reading suggestions.

[2] Stanton, “Outside the Frame: Assessing Partnerships Between Arts and Historical Organizations,” The Public Historian 27, no. 1 (Winter 2005), 19-37.

2 comments