Centering African American history in a public history course

18 February 2021 – Felicia Jamison

I first became interested in public history as a child. My church often had events that celebrated Black history. And at least once a year, my schools would create bulletin boards highlighting the achievements of African Americans. After graduating from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, I knew that I wanted to teach courses that explored how this history has been taught in public spaces.

Author Felicia Jamison gives a tour at the W.E.B. DuBois National Historic Site, Great Barrington, Massachusetts, 2015. Photo credit: Felicia Jamison

I was fortunate to receive a certificate in Public History while a doctoral student, during which I learned about the field and interned at the W.E.B. Du Bois National Historic Site. I taught such a class while a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Maryland. My course, “African American History as Public History,” considers how museums, historic sites, films, public school lesson plans, and the broader public have interpreted African American history since the late nineteenth century. [1]

This semester I will once again teach the course, this time at Drake University, a private college in Des Moines, Iowa. I’ve taught it twice before, at Loyola University Maryland, in addition to the University of Maryland. As none of these universities have a public history program, this class serves as an introduction for most students to the principles of the field.

Overall, I have three main objectives for the course: 1) to center the experiences and voices of African Americans; 2) to introduce students to the field of public history; and 3) to help them engage with local African American history. The class is organized chronologically and analyzes how topics such as slavery, the Civil War, and the Civil Rights Movement are taught in public spaces.

The first week of the course is dedicated to establishing a theoretical and historical framework. I assign readings that concisely detail the creation of the field. We also read and discuss how African Americans preserved and presented their own history due to the exclusionary and racist practices of white-controlled museums. Jeffrey C. Stewart and Fath Davis Ruffins historicize this practice in “A Faithful Witness: Afro-American Public History in Historical Perspective, 1828-1984.” I include short readings on #MuseumsAreNotNeutral, a movement that simultaneously examines the inherent power possessed by museums and pushes for equity in these institutions. La Tanya S. Autry, one of the architects of the hashtag, has created the Social Justice & Museum Resource List, which puts many of these readings in one place.

As this is an introductory course, I regularly assign readings from blogs that are informative, accessible, and ground students theoretically. The blogs that I routinely use are the National Council on Public History’s History@Work and the African American Intellectual History Society’s Black Perspectives. A reading that students enjoy and often cite in their papers is Jessica Marie Johnson’s “Time, Space, and Memory at Whitney Plantation.” The post details how historic sites center and humanize the lives of enslaved people. Johnson’s narrative style is very descriptive and makes the reader feels as if they are visiting the museum. Blogs such as these work very well in introductory classes like this one.

The class also reviews case studies detailing how institutions have dealt with issues involving race. An entire week is devoted to discussing how universities have created projects that uncovered and grappled with their institutional ties to slavery. Later in the semester we discuss the Confederate monument debate and analyze how the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill has dealt with the Silent Sam monument and the resulting student protests concerning its removal from campus. Coupled with lectures, readings, and class discussions, students learn about the ubiquity and practicality of public history. Cases such as UNC’s often empower students to enact change in their own communities.

The major assignments are spread throughout the semester. They include students’ visiting local sites and subsequently writing about their experiences. While at the sites, students complete a primary source analysis form that helps them analyze the historical significance of the site, exhibit, or artwork. Students then write a paper in the first person in which they engage with at least two class readings.

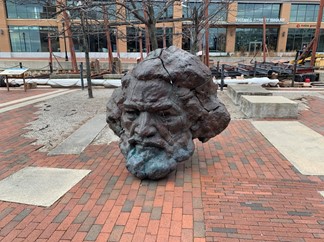

Marc Andre Robinson’s “Frederick Douglass” in Fells Point, Baltimore, Maryland. Photo credit: Felicia Jamison

At UMD, students visited the Anacostia Community Museum and wrote a paper on its creation and connection to the Black community in the nation’s capital. At Loyola, students wrote about their experiences at the Frederick Douglass monument in Baltimore. They examined Douglass’ life, the artist’s motivation for creating the large head, and why it was placed in that particular location. Students emphasized how they were now more attentive to and critical of local monuments’ histories and purposes.

Here at Drake University, students will learn, research, discuss, and write about the dislocation of Black people in the 1960s and 1970s by engaging with the virtual exhibit Undesign the Redline. We will also have a class visit from Representative Ruth Anne Gaines who will share her lived experiences of growing up as an African American woman in Des Moines and her work in the Iowa Legislature. This module allows students to learn how redlining and urban renewal projects disrupted established Black neighborhoods and businesses. Students also learn about the fundamentals of digital and oral history.

Much of the learning is collaborative and occurs during class discussions and in group activities. In one class at UMD, we discussed the issues inherent in teaching slavery to the general public, who may be ignorant and/or uncomfortable with engaging in such conversations. After weeks of learning about how American slavery varied depending on the time and place, I divided students into four groups and assigned each with the task of analyzing a diagram of enslaved people on the Brookes. Each group then explained the image to other classmates, who played the roles of elementary schoolers, middle schoolers, high schoolers, and senior citizens.

Students also created a story time project, facilitated in-depth conversations on the subject, and crafted other interactive activities. Afterward, we had a class debriefing in which students talked about the challenges of discussing slavery with diverse audiences. Group activities such as these allow students to think like public historians by working with colleagues to educate the broader public on various historical topics.

Public history courses offer educators the opportunity to highlight the experiences of local communities of color or other marginalized groups. In this case, centering African American history educates students about the diversity, longevity, and beauty of Black people, and the timeliness of their stories. A final advantage of the class is that it often attracts students from all majors who come to class unfamiliar with the subject matter and leave as more knowledgeable and empathetic people. Students have stated that they truly enjoyed learning about African American history in such a hands-on manner. And of course, teaching the class is always an exciting and educational experience for me too.

~Felicia Jamison is an assistant professor at Drake University. She specializes in African American history and public history. Her research focuses on the lives and experiences of nineteenth- and twentieth-century African Americans who lived in the rural South.

[1] I would like to thank Marla Miller for encouraging me to write this blog. Additionally, Elsa Barkley Brown, my faculty mentor at the University of Maryland, reviewed several drafts of my syllabus and provided invaluable feedback. Finally, I’d like to thank Marwa Amer for suggesting ways to improve this blog post.