Creative nonfiction as public history: a Q&A with author Miles Harvey

22 December 2020 – Amy Tyson

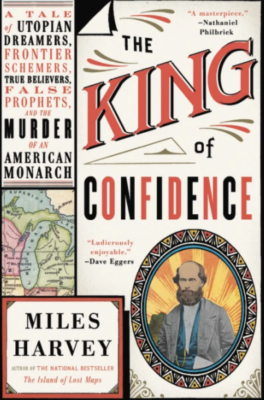

Editor’s Note: Miles Harvey is author of The King of Confidence, A Tale of Utopian Dreamers, Frontier Schemers, True Believers, False Prophets, and the Murder of an American Monarch, which tells the story of James Jesse Strang, a 19th-century con man, who—as a self-proclaimed prophet and king of the universe—led a sect of the Mormon faith called the Strangites. The King of Confidence is a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice selection and a longlist title for the 2021 Andrew Carnegie Medals for Excellence in nonfiction. The following conversation, with History@Work affiliate editor Amy Tyson, about the intersection of public history and creative nonfiction has been condensed and edited.

Amy Tyson: I wanted to talk to you because your books—not just your most recent book, The King of Confidence, but your other books as well—really are excellent examples of historical work and historical labor. So, I was wondering if we could talk about your work, and about this idea of creative nonfiction and its intersections with public history.

Miles Harvey: Like public history, creative nonfiction has many definitions, and they tend to be kind of loose. I think of creative nonfiction as a literary genre that uses forms borrowed from other kinds of storytelling—fiction mainly but also poetry and visual forms like film—to tell nonfiction stories.

The words “story” and “history” share the same etymological root, and I think human beings still have a fundamental yearning to experience the past as narrative in order to figure out where we fit in. I stumbled into narrative history; it’s not something I have training in, and I always worry about that. But I also feel like the need for story in our culture is as strong as it’s ever been. And I guess that’s where I feel as a creative nonfiction writer much closer to the public historians.

AT: Seeing as your work is described as creative nonfiction, could you expound on the creative part? What makes it creative?

MH: What’s creative is in the storytelling. For instance, at the beginning of the King of Confidence, in the prologue, there’s an angel flying around.

At minute 9:45 of this clip from the event, Historical Research in Fiction and Nonfiction, courtesy of C-Span 3, you can hear Miles Harvey read from The King of Confidence. (Miles Harvey, Kathleen Rooney: Top L-R; Amy Tyson; Bottom).

A couple of academic historians have told me, “Well, that’s not history.” I understand why they say that, but I respectfully disagree. I make clear to readers that the angel is not a real figure—that I don’t necessarily believe in the angel, but I’m writing about Mormons who did believe in the angel, and I’m trying to get people into the fevered mindset of mid-19th-century America. I’m not sure when you’re writing about a culture that believes in angels, that angels aren’t part of the history.

I think if people were writing about our times, there would be ways you could explain certain events through numbers or through graphs. But all the data in the world wouldn’t necessarily explain why, for example, millions of people can convince themselves that the results of a presidential election were fabricated, or that the incoming president of United States is involved in a national pedophile and cannibal conspiracy. We can say, “Okay, certain economic factors have alienated lot of people…” but I’m not sure that just those kinds of facts always get at what’s happening. I think there’s something more to history that is not quantifiable.

AT: Could you talk about the contributions that The King of Confidence pushed forward regarding the history of the antebellum era?

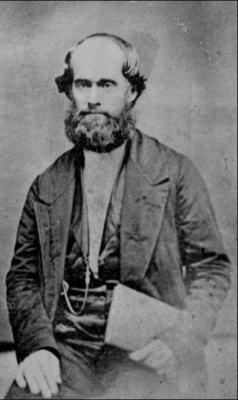

MH: The book is about a guy named James Jesse Strang, who was a rogue Mormon Prophet. After the prophet Joseph Smith’s murder, he was probably Brigham Young’s biggest competitor. And he was this mix of idealism and opportunism.

One of the somewhat controversial ideas about Strang was that he was running basically a pirate colony out of Beaver Island in northernmost Lake Michigan. At least one previous book about him has said that this was all fabrication, all anti-Mormon bias, even though there were numerous stories about it at the time, but this author said, “Where’s the evidence Strang was involved with this?”

Well, I found evidence that put Strang at the scene of one of these crimes. There was an event that hadn’t been written about before in Perrysburg, Ohio, where there was a lot of coverage by a great mid-19th-century small town newspaper editor. There were some horse thefts, and then there was a chase for the perpetrator. A guy was brought back to justice, and it turned out to be one of Strang’s top lieutenants. Then Strang came to town. The local press said something was afoul. And sure enough, there was a jailbreak and Strang, and his top lieutenant, were no longer in town. And so I think more than anyone before me, I’ve put Strang at the scene of a crime.

But I also think I uncovered insight into Strang’s idealism. Strang was an abolitionist. I write in the book that I think it’s the only thing he ever did that was against his own interests. He was an elected member of the Michigan legislature and was a big proponent of a personal liberty law there, which undercut the Fugitive Slave Act. He also welcomed an African American member into his church, nearly 130 years before the mainstream Mormon church did. I got at why he was an abolitionist; I tracked down an event in his young adulthood, where he saw slavery firsthand in Virginia and was appalled by it and wrote about his disgust with it. I think maybe I moved our understanding of his abolitionist impulses further down the road.

AT: The National Council on Public History, and the History@Work blog, has a definition of public history that it is the action of putting history to work in our world. Do you see your book as doing that?

MH: You know, the liberal arts allow us to see the present and future more clearly through the past. I’m writing about a time where truth was very porous and, as a result, people could create their own truth. This was the period of P.T. Barnum and also the period that gave us the phrase “confidence man.”

In the book, I make only two very oblique references to our own time of the Trump era. One is in the prologue, and one is on the last line of the book. I didn’t want to make easy comparisons. I don’t believe that history repeats itself, but I do believe that there’s something we can learn from the past about our own times.

The writing of the book almost coincided exactly with President Trump’s campaign, election, and presidency. And so I saw that our own period was much like the mid-19th century: a time where the truth is malleable. When I first started sending out the book for blurbs, people were saying, “This is an allegory for our own times.” And I don’t object to that; I’m happy about that.

I would have written a different book in a different time. I didn’t set out to write a book that allowed people to view President Trump from the perspective of the 19th century. But you know, I think Trump helped me understand Strang and Strang helped me understand Trump.

And in my view, one of the reasons that Trump has succeeded in inventing his own version of history is that there are so few public intellectuals able to step up and counter that narrative. As someone who came to academia in mid-life, I think it’s largely the profession’s fault. Academics spend a lot of time talking about code switching, you know, but they spend way too little time practicing it. As an academic myself, I understand that there’s a need for us to talk shorthand to each other within our chosen fields. But there’s also a need to open ourselves out to the world and, taking a nod from public history, I wish more academics would take it upon themselves to do that. Being called a “popularizer” shouldn’t be an insult.

The book The King of Confidence is a marvelous volume. The research is broad and deep, the writing crisp and insightful. The concept of “creative non-fiction” is at least a generation old, born in the work of Alex Haley and Tom Wolfe. Academic historians have been using some of the techniques of creative non-fiction, such as setting a scene, for many years. However, too often they lose readers by heavy handed hammering of a thesis, chapter after chapter, and relentless historiographic framing.

Harvey makes a useful observation when he compares the religious fervor of the ante-bellum era with the paranoid theories of QAnon.