Digital public history as folk music hootenanny: Part 3—Toward a multimodal Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project

10 February 2022 – Michael J. Kramer

The Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project, discovered in the silent archives of Northwestern University Libraries Special Collections repository (Part one) and digitally developed through collective effort (Part two), now features a fully-searchable, open-source online archive and a digital exhibit that introduces themes and materials to aficionados and newcomers alike. Where does the endeavor go next?

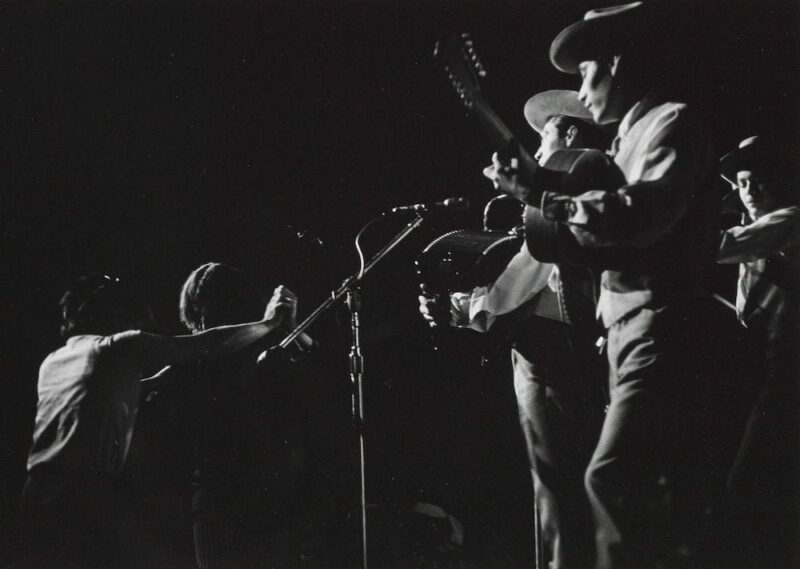

Los Tigres del Norte, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo credit: John Melville Bishop. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

In the coming years, through the support of a National Endowment for the Humanities Digital Projects for the Public Discovery Grant, I am working with students, consulting scholars, and an outside web design firm (Extra Small Design, based in Phoenix, Arizona) on a number of elaborations that build upon the digital repository and introductory digital exhibit. These include a customized online platform for publishing multimedia essays about the Berkeley Festival; an audio podcast series that features younger musicians helping me explore the Festival’s history and significance and record new versions of songs from the original events; lesson plans for teachers using the repository’s artifacts; an oral history repository that presents the memories and expertise of participants at the Festival; social media feeds that share the rich visual material from the archive; and glitching and remix experiments in which new discoveries arise from collaging, rearranging, and experimenting with digitized artifacts.

Collaborations with institutions such as the Arhoolie Foundation seek to link the digital archive to groups engaged with contemporary cultural heritage and traditional music efforts in the Bay Area. I also continue to refine the metadata for the digital repository by working in partnership with Northwestern University librarians and technologists. Northwestern Library, in turn, continues to use the Berkeley Collection as a test case to improve their in-house digital repository system. The hootenanny approach continues.

Most surprisingly, research has led from digital experiments back to face-to-face possibilities for a museum gallery exhibit. With its extraordinary trove of visual material—photographs, posters, and more—the Berkeley archive lends itself well to in-person display. And why not create a hootenanny of modes through which audiences can explore the Festival and its story? A multimodal approach does not position the digital against the analog, the online against the in-person or print publication. Rather, we can bring stories such as those found in the Berkeley Folk Music Festival to audiences more effectively by moving among these different forms of expression.

We can incorporate these multiple modes into a project that becomes more than the sum of its parts: a digital repository allows for in-depth research and access from anywhere; an introductory exhibition, multimedia essays, a podcast, a digitized oral history repository, social media feeds (Twitter, Instagram), and digital lesson plans provide dynamic, online points of entry into the Festival’s historical significance; a gallery exhibit brings the material into curated physical space and also provides opportunities for gathering, for programming, and for continued study. A print catalog provides yet another way in for audiences. Seeing material on the page or on a wall or on the screen is not the same thing. Rather, it allows one to notice new aspects of the material and to hear its stories in ways that come from an ensemble approach.

Seeger at 1963 Berkeley Folk Music Festival workshop. Photo credit: Roland Jacopetti. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

In this spirit, why not even bring digital technologies back into analog modes of gallery curation? Toward that end, I am beginning to collaborate with technologists at Rochester Institute of Technology on a virtual reality room that will allow museum visitors to enter into the weird, wonderful Humbead’s Revised Map of the World. A museum gallery exhibit need not retreat from the digital domain back to the analog, stubbornly resisting it; instead, we can fuse formats of historical exploration, creating a flow among them. We can work multimodally—hootenannistically as it were—so that different kinds of expertise, modalities of access and consideration, and expressions of historical knowledge can flourish.

With the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project, the archive of a folk revival festival itself gets revived. The hootenanny approach makes this possible. By enabling a multiplicity of participants, formats, and curations to join, this conceptualization of digital public history does not privilege any one over the others. Instead, a lively, festive criticality emerges from the movement among them. It turns out there is no one way to sing the song of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival’s history. There are, in fact, many registers, melodies, and ideas to notice, to bring together, and to which one might add one’s own voice.

~Dr. Michael J. Kramer is an assistant professor in the department of history at SUNY Brockport and is the director of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project. Email [email protected], Website: bfmf.net, Twitter: @kramermj, @berkfolkmusfest, Instagram: @berkeleyfolkmusicfestival