Digital public history as folk music hootenanny: Part 1—Finding the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project

27 January 2022 – Michael J. Kramer

This three-part series proposes that digital public history can deepen our study of the American folk music revival and cultural history in the United States. Conversely, it also contends that the folk music revival—with its hootenanny sing-alongs and sense of collective action—offers intriguing democratic models for digital public history. Part one explains how my research on the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project got started as a digital public history endeavor when I discovered a little-used archive of over 30,000 artifacts at Northwestern University’s Special Collections Library. Part two presents the shared effort among librarians, archivists, students, and participants to curate the material digitally. Part three provides a preview of where the Berkeley Folk Music Project will go next.

Although a musical event, the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project began not in sound, but in silence. One day in 2010, while I was an adjunct History and American Studies professor at Northwestern University, I arrived at the oak desk of the university’s Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections. I was in search of underground newspaper articles for a book I was writing. As I was getting ready to leave, archivist Sigrid Perry reached below the desk and pulled out a mimeographed finding aid for the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Collection. The document was torn and folded at the edges, the print fading, a rusting staple barely held the thin sheets of paper together. She explained that hardly anyone had ever looked at the Collection’s materials. Might I be interested in the Berkeley Folk Music Festival materials, she wondered?

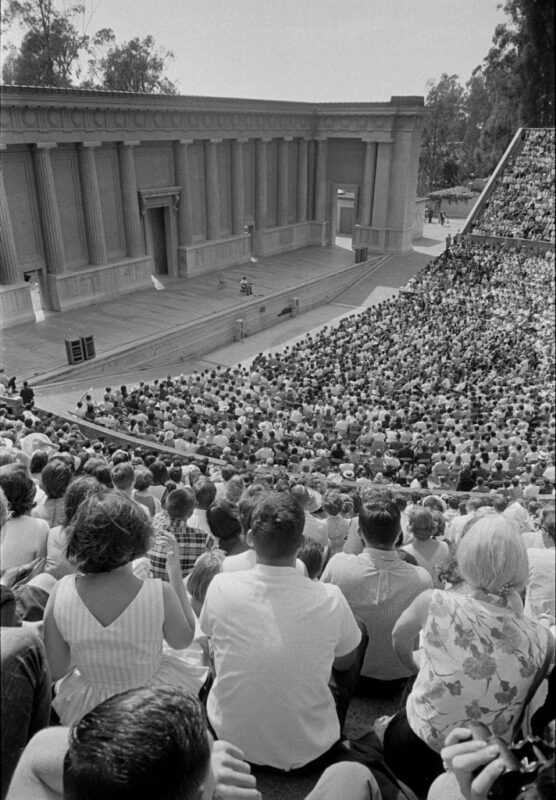

“Mississippi” John Hurt performs at the 1964 Berkeley Folk Music Festival’s closing Jubilee Concert, held in the Hearst Greek Amphitheater on the campus of the University of California. Photo credit: Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

I certainly was. Sitting at a desk in the reading room at Northwestern, I began to thumb through an amazing, seemingly endless amount of material. There were sixty boxes of photographs, clippings, fliers, posters, memos, business records, correspondence, and a bit of intriguing audio and video. The vast majority of it had never been examined closely since Northwestern had purchased it in 1973 from Berkeley Festival director Barry Olivier. The materials told the story of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival, created and run by Olivier between 1958 and 1970 on the campus of the University of California. They offered a new perspective on the cultural history of the folk music revival in the 1950s and 1960s, particularly on the West Coast of the United States. Many know of the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island, where Bob Dylan “went electric” in 1965. Some might remember more commercial groups such as the Kingston Trio or Peter, Paul, and Mary. Others might remain interested in the traditional musicians who resurfaced to perform for predominantly white, middle-class audiences. Most of this history concentrated on the East Coast story. Few consider the folk revival out West, in the Jet Age setting of California after World War II.

After all, California was supposedly the land of the American future, not its folksy past. Yet the Berkeley campus not only became a key site of political activity in the 1960s, it was also a crucial site for folk music. In the same spaces where political events took place, Barry Olivier would also put on the annual Berkeley Folk Music Festival, presenting a mix of traditional and new music. Concerts took place in the grassy Faculty Glade, at campfires among the redwoods and eucalyptus trees, in ballrooms, and at the outdoor William Randolph Hearst Greek Amphitheater. Numerous workshops, panels, barbeques, and coffee hours allowed audiences to explore American and global musical styles and cultures. Performers included Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Doc Watson, Phil Ochs, Jefferson Airplane, Los Tigres del Norte, and many others. Yet few remember the Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Its festive sounds have faded into historical silence and its story locked away in the archive—preserved but largely forgotten.

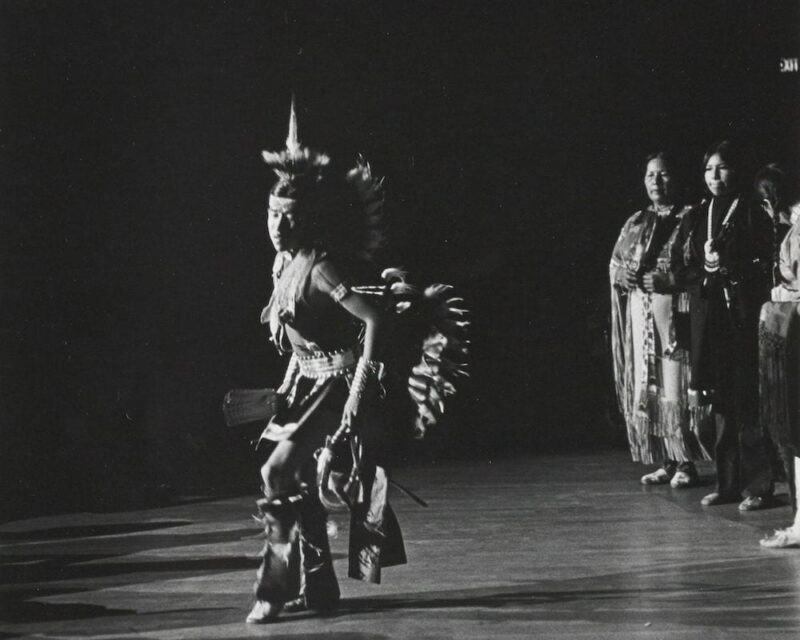

Na Rhma Wa Ci American Indian Dancers, 1970 Berkeley Folk Music Festival. Photo credit: John Melville Bishop. Berkeley Folk Music Festival Archive, Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections, Northwestern University Libraries.

Looking through the materials in the silent reading room of the McCormick Special Collections Library in 2010, I noticed another kind of silence, too. It turned out that Festival director Barry Olivier thought audio tape was too expensive, so little of the Festival made its way to sound recordings. He did, however, hire photographers to document the Berkeley event each year. The most extraordinary part of this archive was its visual material, including about 15,000 photographs. Trapped within these many photographs was, in fact, a noisy history. If you listened imaginatively, the archive buzzed with people gathering to sing and play and listen, to discuss and share and debate the significance of folk music in modern America. Yet all that remained, by and large, were artifacts on a wood table in a quiet library room. Was there, I began to wonder, some way that digitization could reanimate the archive?

A historian cannot magically revive the past as it was, even of a folk revival, a movement itself obsessed with Orphic acts of bringing back the dead’s voices. But might digital technologies offer ways of re-enlivening the past for renewed scrutiny? Just as participants at the Berkeley Festival had sought to link present and past through musical interaction, could we historians, too, join the “folk process,” as Pete Seeger and others called it, by recovering the Berkeley Folk Music Festival’s story using the computer’s abilities to reanimate, remix, and re-present artifacts? Could we, in short, study this event better by approaching it digitally?

Most obviously, digitization would expand access to the Berkeley archive’s materials. But there was more. We could also potentially do more dramatic kinds of analysis and presentation with the transformation of physical artifacts into digital surrogate copies. Once digitized, artifacts could be explored close up or at scale. We could zoom in on details, pair key images with sounds from beyond the collection, and remix the archive’s holdings into new collages, narratives, and patterns. We could potentially take the silent residues of a highly sensory event and make them sing again, but only, as Part two of these three posts shows, with collective effort across different expertise and knowledge.

~ Dr. Michael J. Kramer is an assistant professor in the department of history at SUNY Brockport and the director of the Berkeley Folk Music Festival Project. Email [email protected], Website: bfmf.net, Twitter: @kramermj, @berkfolkmusfest, Instagram: @berkeleyfolkmusicfestival