Excavating subterranean histories of Ringwood Mines and the Ramapough Lunaape Nation, part 1

28 November 2019 – Anita Bakshi

Indigenous People, memorials, landscape, social justice, native americans, public engagement, environmental history

Cover of book resulting from a project funded by the New Jersey Council for the Humanities that built on Anita Bakshi’s design studio class focused on Ringwood, New Jersey, and the Ramapough Lunaape Nation. Image credit: Anita Bakshi

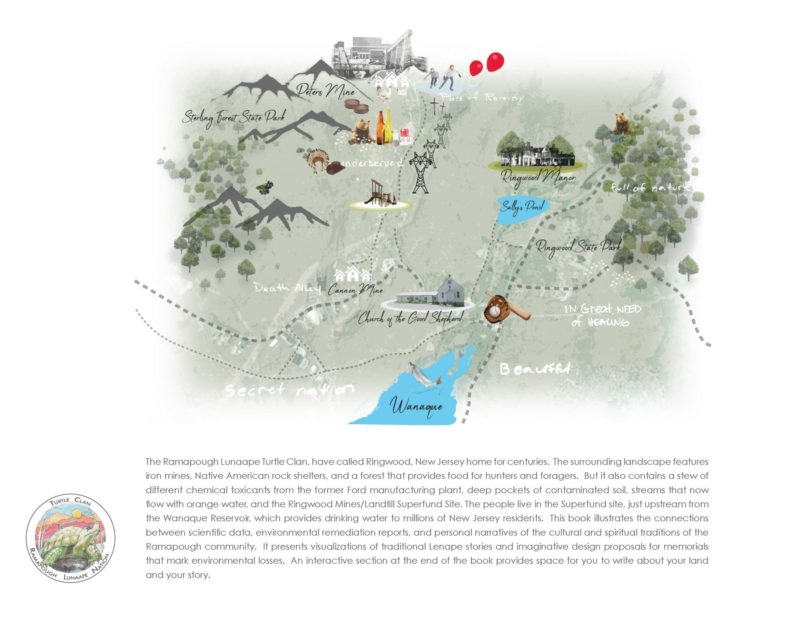

The Ramapough Lunaape Turtle Clan have called Ringwood, New Jersey, home for centuries. The surrounding landscape features iron mines, Native American rock shelters, and a forest that provides food for hunters and foragers. But it also contains a stew of different chemical toxicants from the former Ford manufacturing plant, deep pockets of contaminated soil, streams that now flow with orange water, and the Ringwood Mines/Landfill Superfund Site. Some Ramapough live in the Superfund site, just upstream from the Wanaque Reservoir, which provides drinking water to millions of New Jersey residents.

“The Ramapough and the Ringwood Mines Superfund Site—History, Culture, Education, and Environmental Justice,” a project funded by the New Jersey Council for the Humanities (NJCH) that I directed, focuses on illustrating the connections between scientific data, environmental remediation reports, and personal narratives of the cultural and spiritual traditions of the Ramapough community. Our Land, Our Stories, the book and the exhibition that resulted from the project, includes visualizations of traditional Lenape stories and imaginative design proposals for memorials that mark environmental losses.

I have been thinking about memorials for many years. From 2008-12, I participated in the international Conflict in Cities research group, which explores spatial, social, and political dimensions of ethno-nationally divided cities. I had explored the commemoration of the contested past, looking at how societies mark traumatic histories of conflict, division, and injustice. After I moved to New Jersey in 2013, I began to think about how this framework might apply to the local landscape. I wanted to explore how to commemorate and mark a history of environmental losses, of compromised landscapes, polluted waters, and severed connections.

Back cover of “Our Land, Our People” featuring a map of the study area. Image credit: Anita Bakshi

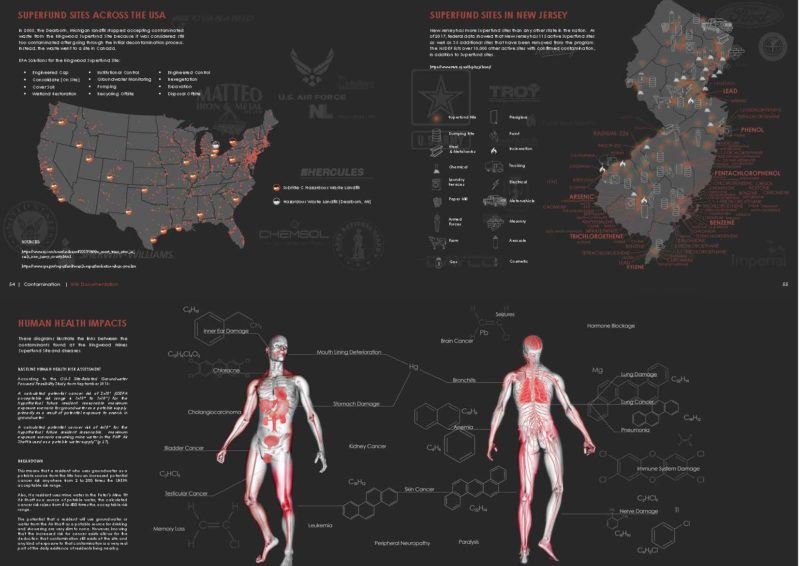

Toward this end, I decided to teach a design studio class in the Department of Landscape Architecture at Rutgers University focused on a Superfund site. The Superfund program was created through legislation in 1980 which authorized the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to identify land that has been contaminated by hazardous waste and is in need of cleanup due to risks posed to human health and/or the environment. Since 2001, the program has suffered from underfunding, and most of the money for cleanup now comes from taxpayers and potentially responsible parties (PRPs). Even though New Jersey has the greatest number and density of Superfund sites in the nation, few people I consulted with when I began my research for this class were familiar with the program.

To decide on an appropriate site for my class, I consulted the list of New Jersey Superfund sites and came across the amazing history of Ringwood Mines. Once an important site for the extraction of iron ore, it was used by Ford Motor Company in the 1960s and 1970s as a dumping ground for toxic paint sludge. Unlike most sites on the EPA’s National Priorities List (NPL), it is a site of continuous inhabitation for many generations, and today is still full of single-family homes. Many residents here are members of the Ramapough Lunaape Turtle Clan—a Native American community with deep roots in the Ramapo Mountains. It was also the first Superfund site to be relisted by the EPA, after it was discovered that significant amounts of contaminants remained on the site despite claims that the remediation was complete. An investigative journalism team from The Record (Bergen Country, NJ), led by Jan Barry, brought this issue to light in the Toxic Legacy series published in their paper in 2005. Work on the site continues to this day.

Detailed information about Superfund sites from the “Our Land, Our Stories” book. Image credit: Anita Bakshi

In spring 2018, I contacted Turtle Clan leader Chief Mann, and he agreed to collaborate with me and my students for a design studio class. The “Marking Environmental Losses” studio documented the various topographies of the site and the history and cultural traditions of the Ramapough. Students were tasked with combing through EPA reports and translating the technical language into graphics that could be more easily digested. They read about Native American history and the industrial history of the regional iron mines, met with Chief Mann, toured Ringwood, and spoke with a number of other project partners. At the end of the semester, they created a series of memorial design proposals, presenting possibilities for marking environmental losses in the landscape.

In part two of this post, I will discuss the process of creating this project in more detail.

~Anita Bakshi is an Instructor in the Department of Landscape Architecture at Rutgers University. She has a Master of Architecture degree from the University of California, Berkeley. Following several years in architectural practice, she received her Ph.D. in the History and Theory of Architecture from Cambridge University.