Excavating subterranean histories of Ringwood Mines and the Ramapough Lunaape Nation, part 2

03 December 2019 – Anita Bakshi

advocacy, Native American, methods, Indigenous People, social justice, environmental history, public engagement, memory, food, sense of place, interpretation

View north along Interstate 287 at Exit 57 (Skyline Drive, Ringwood) in Oakland, Bergen County, New Jersey. Image credit Famartin This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Editor’s note: this is the second in a two-part series. Part 1 was published on November 28, 2019.

I first visited Ringwood, New Jersey, in February of 2018 with a group of fifteen students enrolled in my design studio class at Rutgers University’s department of landscape architecture. Although we knew about the contaminants and toxins that lingered deep in the soil, everything looked so normal. We saw a beautiful wooded landscape, slightly subdued by the rainy weather, interesting herbaceous foliage, and a number of cute, tiny frogs.

We were led behind the chain-link fence that marks the Ringwood Mines/Landfill Superfund site, where we began to see 55-gallon drums and orange fencing. Hikers who move from Ringwood State Park down the Hasenclever Iron Trail are also able to walk right through parts of the Superfund site without encountering any signs of what lies below their hiking boots.

But we had studied EPA reports that detailed the sludge removal locations, and outlined facts and figures about the PCBs, DEHP, and VOCs trapped in the paint sludge in an unknown pattern in the woods, after Ford Motor Company contractors made clandestine deposits in their “midnight landfill” in the 1960s and 1970s. We knew that barrels and barrels of toxic material had been dumped down the shaft of the old iron mine that ran 1,800 feet below ground. Moving deeper into the site we encountered running streams and ponds where the surface of the water at times exhibited a perverse, unnatural sheen—a kaleidoscope of refracted colors on an oily substrate. This is where, just a few decades ago, the Ramapough Lunaape Turtle Clan once used to swim and ice skate, and to drink from the clear running water.

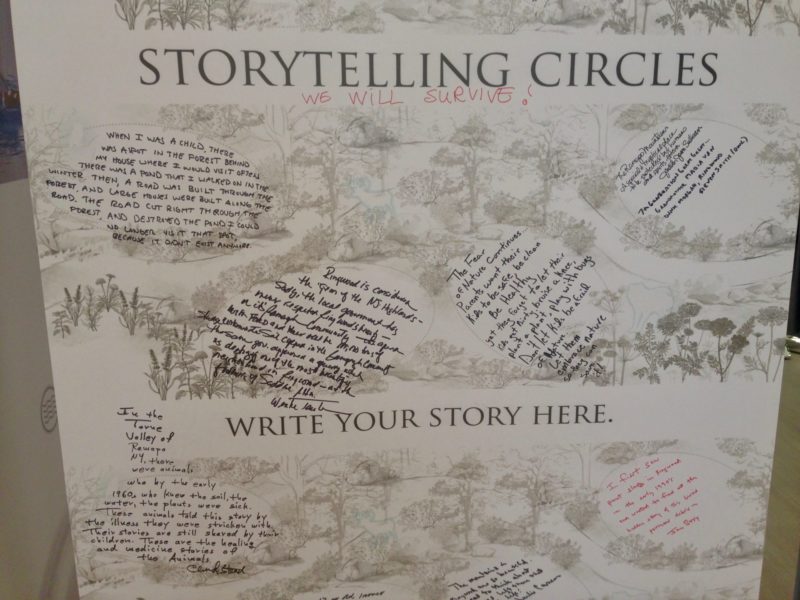

Anita Bakshi’s students used Storytelling Circles as a method to gather perspectives from Ringwood residents. Image credit: Anita Bakshi

The project materials present, side by side, detailed environmental data from EPA reports and scientific studies alongside narratives of human experience. While scientific studies provide knowledge, they can also strip away significance. Using numbers, figures, and statistics to describe environmental losses, this abstract and academic language is sterile; it misses something vital and important in terms of human experience. There is more to Superfund sites than contaminants and remediation strategies. They are part of the web of environmental relationships that define the landscapes in which we all make our home. The book and the exhibition communicate the impact on human communities and the transmission of cultural practices connected to the land. This is an approach for advocating for environmental justice by elucidating and representing the connections between the environmental, cultural, and political histories of the Ringwood Mines Superfund Site.

“Climates of Inequality” exhibit, Newark, New Jersey, October 2019. Image credit: Anita Bakshi

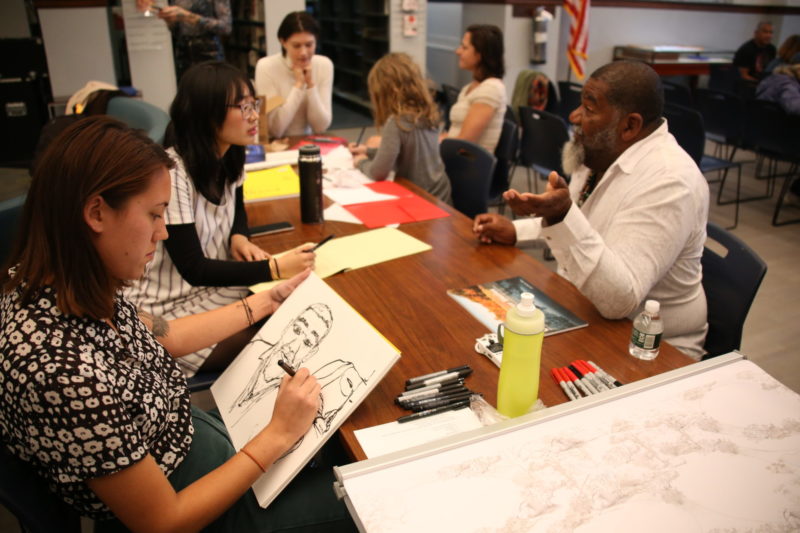

Sketch artists at a storytelling session. Image credit: Anita Bakshi

The multiple, contested narratives about the history of contamination and cleanup in Ringwood required us to experiment with how we might represent these divergent site narratives and histories through visualized stories, drawings, and documentation. This resulted in a 100-page book, Our Land, Our Stories: Excavating Subterranean Histories of Ringwood Mines and the Ramapough Lunaape Nation, and a panel within the Humanities Action Lab’s traveling exhibit, Climates of Inequality: Stories of Environmental Justice, which opened in Newark, New Jersey, in October 2019. The book consists of thoroughly researched and documented information about the site and its residents, visualizations of complex environmental data from EPA reports, imaginative renderings of traditional Lenape stories, and essays from five key project partners. It also includes an interactive section in which readers are invited to write and sketch. The book and the exhibit panel clarify contested narratives through clear graphic representations that illustrate the connections between different sets of scientific data, environmental remediation reports, records of the site’s industrial history, and personal narratives of the cultural and spiritual traditions of the Ramapough community.

My team is now embarking on a year-long process of gathering feedback and eliciting conversations about the work through a variety of forums, including a series of storytelling sessions that will be visually documented by sketch artists, as well as a forum that will highlight the experiences of different Native American communities with food sovereignty—the right to healthy and culturally appropriate food—in the context of contamination. We seek to enhance outreach and communication efforts to allow for the development of understandings of deeper connections to the landscape by illustrating traditions, cultural meanings, and emotions. The materials are aesthetically pleasing and visually engaging—in contrast to the manner in which much scientific data is often presented to audiences. This will allow people from different backgrounds and perspectives to gain a greater understanding of environmental justice issues and unevenly dispersed impacts.

This project leans heavily on the environmental humanities for thinking through new forms and mechanisms for presenting information and raising awareness. Ultimately, people must see the interconnections between themselves, other communities, and environmental systems. They might then be motivated to participate in advocacy efforts. This project creates visual representations that illustrate this interconnectivity—from bioaccumulation of toxins in the food web to the potential contamination of the Wanaque Reservoir, which provides drinking water to 2 million people. Through all these media we have created resources for educators around the country to teach about environmental justice, Superfund, Native Americans and contemporary land issues, and the role of the state agencies and the EPA in protecting the environment and human health.

The exhibit will be on display at Newark Public Library through early December 2019. If you’d like to request a copy of the book for educational purposes, please visit my website.

~Anita Bakshi is an Instructor in the Department of Landscape Architecture at Rutgers University. She has a Master of Architecture degree from the University of California, Berkeley. Following several years in architectural practice, she received her Ph.D. in the History and Theory of Architecture from Cambridge University.