Folklore and the roots of public history training in Cooperstown

03 February 2017 – Will Walker

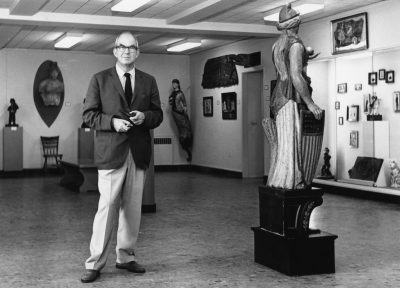

Louis C. Jones in the Folk Art gallery, New York State Historical Association. Photo credit: New York State Historical Association.

In January 1950, in a keynote address at the annual meeting of the Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul, pioneering museum studies educator Louis C. Jones illuminated the vital connection between folklore and history and its relationship to the public history community. Jones was director of the New York State Historical Association at the time and, a decade and a half later in 1964, he would found the Cooperstown Graduate Program, the first master’s degree program in the United States explicitly designed to train professionals to work in history museums.[1] In St. Paul, Jones made the case that museum professionals should embrace folk culture and social history, and he suggested that this shift in focus away from traditional, elite narratives would be transformative for U.S. museums. Jones prodded his colleagues, stating that the:

historical societies of America must start thinking, in a way they have never thought before, about the workingmen and women who are the essential creators and defenders of our democratic faith, about the men and women who caught the later boats and whose children who stand among us as proud, full-fledged citizens.[2]

Working people, immigrants, and others whose stories had largely been ignored by museum professionals should, Jones maintained, be the focus of a transformed public history.

“Hop picking,” Otsego County, New York, postcard. Image credit: New York State Historical Association.

Louis Jones had an unusual background for a historical society director. Trained as a literary scholar, he gravitated to folklore as a young English professor at the New York State College for Teachers in Albany in the 1930s. His research and teaching, primarily on New York State folk culture, spurred an interest in social history, and the connections he made in Albany led him to be offered the directorship of the New York State Historical Association (NYSHA) in the mid-1940s. Relocating to Cooperstown, Jones set about building The Farmers’ Museum, an outdoor living history museum in the vein of Old Sturbridge Village, as well as expanding the institution’s history and art collections. He brought his folklorist’s perspective to historical interpretation, arguing against an emphasis on war, politics, “leaders and the rich” and in favor of narratives of working people’s lives. Reflecting on these early years, Jones stated that he “found comfort among the social historians” and wrote that he believed that “[h]istory had to seek an all inclusiveness it lacked in those days.”[3]

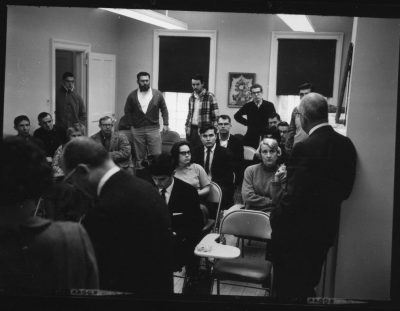

Jones speaking with the first class. Photo credit: Milo Stewart.

Jones understood that he was offering a challenging and progressive vision for history museums, and he recognized that the best way to initiate such change was by educating the next generation of public historians. Therefore, he wove his vision into the DNA of the master’s program he founded, and alumni subsequently carried it to numerous museums, historical societies, historic sites, cultural institutions, and even other museum studies programs throughout the United States. Jones along with another folklorist, Bruce Buckley who came from Indiana University, designed a curriculum in Cooperstown that emphasized practical museum skills, fieldwork, oral history, and social history research in two related tracks—History Museum Studies and American Folk Culture. Each year, students’ traversed the rural villages and farms of Central New York State, uncovering stories of skilled labor, craft traditions, gender dynamics, farming practices, animal husbandry, transportation, water systems, and much more. Talking to people about their lives, work, and material culture was an essential skill that students acquired. Moreover, they learned how to create exhibitions, design educational programs, manage collections, and administer non-profit institutions. Students practiced these skills and incorporated narratives of working people into interpretation at The Farmers’ Museum and disseminated them to museums, historic sites, and living history farms across New York State and beyond.

Jones’s most famous student, public folklorist Henry Glassie, embodied this marriage of folklore and social history. A member of the first class of the Cooperstown Graduate Program in 1964-’65, Glassie has recently commented that he “always had a vision of engaged scholarship, right from the beginning—a folkloristic version of public history.”[4] In the late 1960s, one of his first projects after graduate school was documenting in-depth the Poor People’s Campaign and creating a photography exhibition about it. Around the same time, he was involved in the founding of the Smithsonian’s Festival of American Folklife and, as state folklorist of Pennsylvania, he worked with educators to create a “bibliography of ethnic culture for Pennsylvania.”[5] Moreover, in the early 1970s, he was a major consultant for Conner Prairie in Fishers, Indiana, and the Museum of American Frontier Culture in Staunton, Virginia.[6] Although Glassie is certainly an exceptional example, he is representative of a broader movement among young public historians toward engaged, pluralistic, and community–based scholarship and practice in this period. As demonstrated by Glassie, the organic intersections between folklore and history were at the core of this transformation.

In the years following the founding of the Cooperstown Graduate Program, the black freedom struggle, women’s liberation, and other movements for social justice pressed public historians further in their efforts to document and share subaltern narratives and expand the inclusiveness of cultural institutions. A new generation of public historians called for the critical interrogation of the structures of power that fueled inequality, racism, and sexism. Folklorists like Jones found their semi-romantic notions of working people’s lives challenged by analyses that centered systemic oppression and institutional racism. Today, the curriculum in Cooperstown reflects these changes. Nevertheless, Jones’s vision still resonates with an understanding of public history as inclusive and public-oriented and as a field that emphasizes narratives of the ignored or under-represented.

~ Will Walker is associate professor of history at the Cooperstown Graduate Program (SUNY Oneonta) and co-lead editor of History@Work. This is the second post from the “Radical Roots: Civic Engagement, Public History, and a Tradition of Social Justice Activism” collaborative research project. You can find the first post here.

[1] Winterthur and the Hagley Program, both founded in the 1950s, pre-date the Cooperstown program; however, neither was founded explicitly to train history museum professionals. Originally, there were two related programs at Cooperstown: History Museum Studies and American Folk Culture. Students often took courses in both areas. The folk culture program was discontinued in the 1980s. The Cooperstown Graduate Program is an academic program of SUNY Oneonta.

[2] Jones, “Folk Culture and the Historical Society,” 12.

[3] Jones, Three Eyes on the Past, xxiv.

[4] Henry Glassie and Barbara Truesdall, “A Life in the Field: Henry Glassie and the Study of Material Culture,” The Public Historian 30, no. 4 (Fall 2008): 69.

[5] Glassie and Truesdall, 71, 73.

[6] Glassie and Truesdall, 75.