Reflections on Guns and Public History at the 2019 NCPH Annual Meeting

30 May 2019 – Joan Zenzen

gun violence, hackathon, National Park Service, plenary, NCPH Board Member Posts, 2019 annual meeting, Hartford series 2019

Editors’ Note: This post is one of two that will highlight reflections on events at the March 2019 National Council on Public History annual meeting.

Public plenary on Coltsville National Historical Park and gun violence. From left to right: Rev. Henry Brown, Warren Hardy, Sarah Pharaon, Hartford Mayor Luke Bronin, Thea Montañez, Iran Nazario, and Rebecca Stanfield McCown. Photo credit: Kelly Schmidt

I felt honored and humbled. Here I sat with a few hundred fellow public historians in a historic church listening to community members share their hopes about how a new national park might collaborate with their neighborhoods and help make a positive difference to life in Hartford, Connecticut. The US National Park Service (NPS) had a representative participating in the conversation while the new leadership for Coltsville National Historical Park (NHP) sat in the front pews and took in every word. As someone who has written about national parks and their beginnings her entire professional life, the public plenary for the 2019 National Council on Public History (NCPH) annual meeting at Hartford’s Center Church presented me with an unmatched opportunity to see NPS in action.

I came away from the plenary and other events at the 2019 conference with a big take-away: that public history creates sacred space for conversing, for trying out ideas, and for making change.

The NCPH’s 2019 conference made dialogue about guns and gun violence an important subject woven into the overall Repair Work theme. Coltsville NHP is the home of Samuel Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company, which famously produced the Colt .45 revolver, the standard-issue weapon for the US government in the late-nineteenth century. The cavalry, infantry, and artillery all had Colt .45s in their holsters when they fought in the last of the Indian Wars, such as the Great Sioux War of 1876 (which included the Battle of Little Bighorn), forcing American Indians onto reservations.

Today in the United States, guns are a heated topic, and NCPH did not shy away from the juxtaposition of a national park focused on guns and the contemporary scourge of gun violence, which permeates Hartford. According to the mayor’s office in December 2018, 22,000 children, nearly three-quarters of the city’s youth, live in areas of frequent gun violence. Hartford is less than 50 miles from Newtown, Connecticut, where Adam Lanza in December 2012 gunned down 26 people (including 20 six- and seven-year olds) at Sandy Hook Elementary School, in addition to killing his mother nearby. Nationally, gun violence is a constant danger. Using media reports and official records, Everytown for Gun Safety found that there were 173 mass shootings (defined by four or more people killed, not counting the shooter) in the US between 2009 and 2017. As I write this piece in late April 2019, three well-publicized shootings took place within three days of each other: University of North Carolina-Charlotte (two people killed and four wounded); Baltimore (one person killed and seven wounded at two cookouts at an intersection); and Poway, California (one person killed and three wounded at a synagogue).

NCPH engaged in discussions about gun violence beyond the public plenary. On Wednesday, public historians brought their skills to the gun debate with Seeking to Mend: Digital Documentation and Mass Gun Violence Hackathon. Participants, including myself, brainstormed how best to create a digital site that combined public history projects, memorial sites, and available data on mass shootings. The result www.aftertheshots.org, went live at the end of our nine hours together. The site includes a Rapid Response Kit for public historians to access after an event, trauma and self-care resources, aggregated data on gun violence, historical interpretation examples, and educational materials.

Before the public plenary on Friday, I joined a small walking tour of the area designated as part of Coltsville NHP. Congress designated Coltsville NHP in December 2014; the park will be officially established once two key properties, the Forge and Foundry, are acquired. In the meantime, NPS has been reaching out to Hartford city officials and local communities and offering limited public programs.

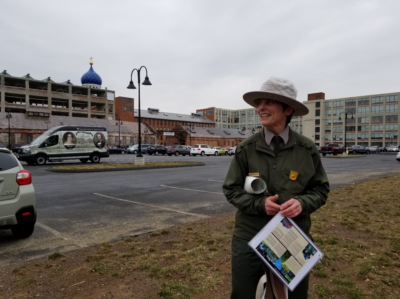

NPS Ranger Amy Glowacki led a tour of Coltsville National Historical Park. The park’s interpretive van sits in the adjacent parking lot. The blue onion dome, first placed by Samuel Colt and reconstructed after a devastating fire soon after his death, marks the manufacturing site. Photo credit: Joan Zenzen

Our walk was entirely outside (in spitting rain) because NPS does not currently own any buildings. Even after the agency acquires the two brownstone buildings containing the forge and foundry, the park will include limited property. Following the Lowell NHP model, the Coltsville park will be a public-private partnership that will rely upon collaboration to tell the stories of Sam Colt, his factory, his sudden passing in 1862, his wife Elizabeth’s ownership of the company, and her memorialization of her late husband. Factory workers lived on the factory grounds, and NPS will also delve into their experiences.

The NCPH public plenary went directly to the sensitive and politically charged relationship between Coltsville’s history of gun manufacturing and the impact of guns and gun violence upon Hartford today. This plenary allowed community members and NPS to have an open and productive conversation about the national park. Leah Glaser, historian at Central Connecticut State University who helped organize the event, stated that this was the point. Organizers wanted a community conversation to foster exactly what public historians advocate for, shared inquiry and shared authority in the planning of the park. Public historians had had their chance to deep-dive into the research and its translation into a park on Wednesday at the Organization of American Historians-NPS Scholars Roundtable, hosted by NCPH.

For the plenary, Sarah Pharaon of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience facilitated the conversation with compassion and humility. She provided a safe space for discussion and offered a light hand so that all participants had time to speak. Hartford Mayor’s Chief of Staff Thea Montañez sat on the panel and noted that some neighborhoods have so much gun violence that their inhabitants get de-sensitized and think the violence is normal. She emphatically stated that “it’s not—not normal.”

Montañez, later in the conversation, referred to Coltsville as a “sacred space,” and I want to explore this idea further. I attended Margo Shea’s On the Fly Conversation about the Catholic Church’s Sex Abuse Scandal, also at the annual meeting. Shea opened her session by stating that public history can create space for reflection and emotion, and during the course of the discussion, the half dozen of us in attendance came to the realization that public history was a sacred space. Public history gives space for some of the most intimate, weighty, controversial, and provocative conversations. For Montañez at the plenary to name the new national historical park as sacred space means that the mayor’s office, and by extension the city itself, sees the park as a safe space for exploring some of the most sacred work of the city—a space for confronting the history of guns, gun manufacturing, and the reality of gun violence today. We, as public historians, are engaged in this examination, in this sacred space.

But the idea of sacred space is complicated, especially when thinking about gun violence and a national park. Can a place devoted to memorializing the mass manufacture of lethal weapons serve as a meaningful setting for talking long and hard about gun violence? I think there is promise for profound deliberation, given NPS’s increasing use of civic engagement and shared authority. Public historians have a crucial role in facilitating these partnerships, creating a sacred space, and using our professional skills to inform and shape this conversation. I see this sacred space directed toward action and results, not reverence or veneration.

Three other members of the plenary panel came directly from Hartford. Rev. Henry Brown helped found Mothers United Against Violence, and he kept bringing the conversation back to the families and the kids directly affected by gun violence. He wanted Coltsville NHP to provide a safe harbor for these children. Rev. Brown also called out the bigger problem of racism. From his perspective, when black kids are murdered no one talks about it like they do when white kids are killed. Two panel members, Warren Hardy and Iran Nazario, had once perpetrated gun violence but have since dedicated their lives to empowering youth and promoting peace. Hardy founded HYPE (Helping Young People Evolve), and he challenged the audience to view the status quo as a life and death situation needing direct action. He asked, “What’s the best idea I can come up with? What’s going to save lives?” Nazario founded the Peace Center of Connecticut. He sees Coltsville NHP as a place to build trust with the families and offer activities and opportunities for engagement between black people and white people to break down racism. Nazario recognized that NPS has so many voices to work for change.

Rebecca Stanfield McCown, director of the NPS Stewardship Institute, at Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller NHP in Woodstock, Vermont, answered these calls with specific examples of how NPS has engaged with communities at other parks. NPS has adopted an Urban Agenda, “an unprecedented strategic alignment of parks, programs, and partners,” which informs NPS’s treatment of urban parks, including Coltsville. McCown, a black woman with a PhD in natural resources, represented the high ideals and promise of the agency. She talked about Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site and how NPS has fostered dialogue there and at other sites. She noted that NPS provides space (she didn’t say “sacred,” but maybe she meant that?) for difficult conversations about diverse narratives of the history of the United States. Communities needed to identify ambassadors, McCown stated, to work with NPS on what was most important to the communities.

My experience in Hartford, whether at the Hackathon or on the Coltsville NHP tour or in the public plenary, brought me face-to-face with examples of how public history makes room, or provides sacred space, for discussion and action. A big topic in Hartford was guns and gun violence. Others included #MeToo, Confederate monuments, and mass incarceration. Public history uses rigorous scholarship and inclusive debates to uncover the past and inform the future. I sat honored and humbled, watching as public history made sacred space for all of us to confront the major topics of the past and present.

~Joan M. Zenzen serves on the NCPH Board of Directors. She is an independent historian based in the Washington, DC area. She writes histories for US federal government agencies, especially the National Park Service. She also conducts oral histories for various clients, including non-profits and local governments. Her website: www.joanzenzen.com. Reach her at [email protected]

The author thanks Cathy Stanton, Leah Glaser, and Margo Shea for their help in formulating this post.