Helen Matthews Lewis: An unruly woman tests historical authority

08 March 2017 – Judith Jennings

“If you just pussy foot around and try to be safe, you won’t get anything done, and they’ll still fire you. Might as well accomplish all you can.”

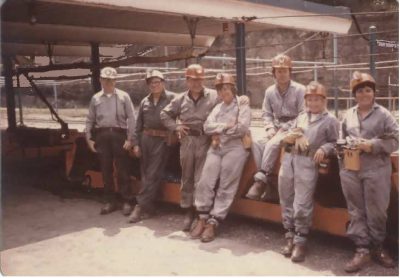

Helen Matthews Lewis with a group of miners. This photo, along with the others featured in the post, come from Lewis’s scrapbook. They originally appeared in Judith Jennings and Patricia Beaver, eds., Helen Matthews Lewis: Living Social Justice in Appalachia. Photo credit: Judith Jennings.

Sentiments like these earned Helen Matthews Lewis the title of an unruly woman. As an unruly oral historian, her work tests the boundaries of historical authority and raises larger questions concerning community-based social change, the radical roots of oral history, and the future of public history.

Born in 1924 in rural Georgia, she developed her own radical roots early. Learning from suffragist teachers at Georgia State College for Women in the 1940s, she became involved in state politics and desegregation. She married reluctantly, and, in 1949 completed a master’s thesis in sociology on “The Woman Movement and the Negro Movement: Parallel Struggles for Rights.”

Lewis with mining pony. Photo credit: Judith Jennings.

In 1955 Lewis moved with her academic husband to Clinch Valley College (now the University of Virginia’s College at Wise), newly established in the western Virginia coalfields. As a faculty wife, she could not teach at the college. She focused instead on learning about her surroundings in central Appalachia, especially the impact of coal on social and economic conditions. In the mid-1960s, she received a U.S. Bureau of Mines grant to research the effects of mechanization on coal miners and their families.

In 1967, Lewis joined the faculty at East Tennessee State University, an hour away from Clinch Valley but still in the coalfields. She began developing a place-based curriculum centered on student learning from and with community members through oral interviews, research projects, and cultural presentations. She gladly shared her curriculum, including oral interviews as a key pedagogical methodology, with colleagues across the region, creating what are now recognized as the first Appalachian studies classes.

Yet when Lewis used local studies to question the status quo, she soon learned how power and authority shape relations between the teacher and her academic institution. She and her students spoke publicly about the long-term patterns of unfair tax advantages for the coal industry and the environmental damages of mining. When the coal companies complained, the university fired her, disrupting her historical authority as a teacher.

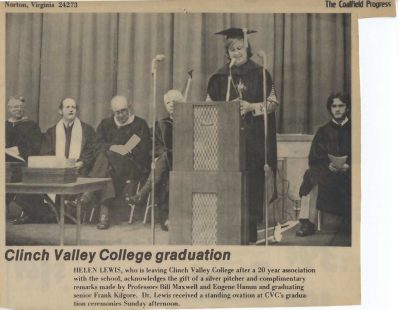

Lewis at Clinch Valley graduation. Photo credit: Judith Jennings.

Lewis returned to Clinch Valley College, which by 1969 allowed marital partners to teach. She continued to develop Appalachian studies classes and completed her Ph.D in sociology at the University of Kentucky. She also continued to encourage students to research and speak about the social impacts of coal mining. Again, local coal operators complained to college administrators. In 1977, Lewis, not one to pussy foot around, resigned to become an unruly oral historian operating outside the academy.

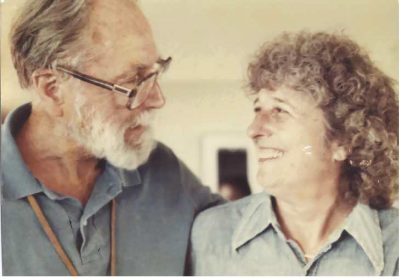

Lewis with Myles Horton. Photo credit: Judith Jennings.

She divorced and made her living as a circuit-riding sociologist, teaching periodically at Appalachian State University and working with two key social change organizations. She led a multi-year History of Appalachia film project at Appalshop, the Kentucky-based media arts and education center. She joined the staff at the Tennessee-based Highlander School for Research and Education, becoming “a pivotal figure,” alongside founder Myles Horton, in developing local and global participatory action research and popular education programs.

Lewis, who Dan Kerr calls a “self-proclaimed oral historian,” engaged low-income mountain women in narrating and analyzing their paid and unpaid work experiences. In doing so, she was sharing historical authority for crafting and meaning making in ways later identified by Michael Frisch. Yet, her oral interviews were a means to social change, not an end in itself. The women collectively identified their skills and earning potentials and helped create the first curriculum for Highlander’s Economics Education Program.

In 1987, Lewis met Maxine Waller, head of the Ivanhoe Civic League, formed to foster local economic development in the Virginia town. As Lewis explains, Highlander wanted an in-depth participatory research project with an Appalachian community experiencing economic transition. Lewis was also working with the Glenmary Research Center, a faith-based feminist organization of former nuns. The nuns wanted to study local theology. The three unlikely partner organizations embarked on what became a five-year process of sharing historical authority at the community level.

Waller and the Civic League participated on the condition that a community history book would be produced. The League wanted the publication quickly. Early on, as Lewis recalls, the book brought to light the problems of being fully participatory. She opted to turn over the publication to professionals, short-circuiting the participatory editing process. Volume One, Remembering Our Past: Building Our Future, appeared in 1990 and won an award for best book on Appalachia. Yet tensions continued.

Lewis recognizes that, as a scholar, she had considerable personal investment in the project. Waller argued that more attention was going to Volume Two than to the community. Lewis and Waller clashed, cried, prayed, and celebrated their roles as researcher and organic intellectual. Mary Ann Hinsdale, the feminist theologian, faced criticism when her ideas of liberation theology ran counter to the community’s religious views. The process of sharing historical authority became interrupted and strained.

Yet the partners persevered and created successful participatory community history opportunities. Together, they analyzed economic factors, conducted interfaith Bible studies, and presented storytelling performances based on oral histories. The three women leaders forged trusting relationships based on their shared belief that ultimate historical authority comes from the lived experiences of community members. In 1995, disrupting the authority of top-down history, Hinsdale, Lewis, and Waller co-authored It Comes From the People: Community Development and Local Theology.

Helen Matthew Lewis and her lifelong work not only indicate the radical roots of oral history but also provoke larger questions about the future of sharing authority in oral and public history. What are the appropriate boundaries for academics using oral interviews as a pedagogical tool for social change? How are those boundaries decided? What are the appropriate boundaries between community-based research for social change and public history? Who decides?

~ Judith Jennings is an independent scholar who earned her Ph.D. in history at the University of Kentucky. She served as the founder of the University of Louisville Women’s Center and the executive director of the Kentucky Foundation for Women. She is the co-editor with Patricia Beaver of Helen Matthews Lewis: Living Social Justice in Appalachia.

*This post is part of a series from the “Radical Roots: Civic Engagement, Public History, and a Tradition of Social Justice Activism” collaborative research project. You can find other posts in the series here. Research project members will be presenting a mini-symposium at NCPH’s annual meeting in Indianapolis on Friday, April 21 from 1:00-5:00 pm.

Helen has had such a fascinating career. Her story is an important part of how Public History has evolved and continues to change!

Thanks! Everyone can learn more about Helen Matthews Lewis and her community change work at the Mini-Symposium on Radical Roots: Civic Engagement, Public History,

and a Tradition of Social Justice Activism on Friday, April 21st from 1:00 to 5:00 during this years conference.