Competing histories or hidden transcripts? The sources we use

13 March 2019 – David Rotenstein

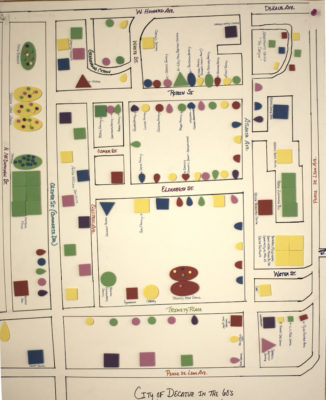

Memory map of the Beacon Community created for Black History Month and photographed in 2014. Photo credit: David Rotenstein

In January, History@Work published Heather Carpini’s important essay on competing histories. Carpini’s appeal for historians to dig “deeper, past the obvious sources, into the lives of the people who shaped, and were shaped by, a certain place” is an essential call to action. This values- and human-centered approach to historic preservation is gaining traction. In this essay, I want to address some of the pitfalls of digging deeper into community histories.

To do the essential work that Carpini recognized, public historians and historic preservationists need to rewrite the standard field manual that has crystallized over more than fifty years of production-line cultural resource management (CRM). Tight budgets and schedules, poorly trained fieldworkers, and implicit bias all play a role in reinforcing an approach to CRM that Richard Hutchings has described as the “McDonaldization of Heritage Stewardship.”[i] It’s going to take a lot more than recognizing that history is complicated; we need a substantial course correction.

In more than 30 years of working in and around CRM, I have had clients and supervisors who made it very difficult to dig deeper. One client explicitly instructed me not to speak with people who lived in the communities where I was doing Section 106 work. Programmatic agreements, streamlined compliance rubrics, and economics make it very difficult to do thorough and conscientious fieldwork.

I have long been concerned with these issues, especially because I come from an academic background that includes undergraduate and graduate training in folklore and folklife. Speaking with the people who make and use material culture is hardwired into our methodologies. The idea of competing histories and what political scientist James Scott calls “hidden transcripts” have become really significant to me over the past several years as I have worked with people affected by displacement and erasure.

Hidden transcripts are texts that emerge in social spaces defined by dominance and oppression. They are the stories and artifacts people create and conceal from outsiders as acts of resistance and cultural preservation.[ii] Some examples of hidden transcripts include family histories told only to kin. In many traditional communities, kinship extends well beyond consanguinity and these stories oftentimes are community histories.

Other examples are the vernacular museums created in homes, churches, and community centers that tell the stories that competing historical institutions (academics, grassroots preservationists, government agencies) have erased, tokenized, or marginalized. I encountered these in Decatur, Georgia, where lifelong residents made memory maps of the African American community destroyed by decades of environmental racism, urban renewal, and gentrification (see image above).

In Silver Spring, Maryland, residents of a historically Black neighborhood created a history exhibit in a county-run community center. The exhibit debuted about a decade ago after the local historic preservation organization produced a documentary and published books that omitted African American history and the contemporary community. “We don’t exist to them,” one lifelong resident told me in a 2018 interview.

Lyttonsville Community history exhibit, Gwendolyn E. Coffield Community Center. Photo credit: David Rotenstein

The histories that African American residents in Decatur and Silver Spring are competing against are ones created by grassroots organizations and government agencies. Decatur’s Beacon Municipal Complex features an exhibit on Black history in the space it occupies (the city demolished two historically-significant equalization schools to redevelop the complex).

Researched and designed by New York City-based consultants, the exhibit angered many current and former Black Decaturites. It presents a sanitized and incomplete history, several people have told me in interviews I have done since 2015. A consistent gripe is that the stories told and the people selected to tell them derive from one individual.

History under glass, Beacon Municipal Center, Decatur, Georgia. Photo credit: David Rotenstein

When I first began asking about Black history in Decatur, almost all of the people I initially spoke with told me that I needed to speak with this individual to learn about it. My earliest articles about Decatur prominently feature interviews with this person and the snowball sample I developed from the information I obtained.[iii] My sample enlarged substantially after several years and after people independently learned that I was researching Decatur’s Black history, they sought me out. Despite this expanded sample, my early publications reflect a distinct bias.

Similarly, in Silver Spring, when I first began asking where I could find the community’s Black history, most people pointed me towards a single lifelong resident of Lyttonsville, a community that traces its roots to 1853 and the four-acre farm that free man of color Samuel Lytton bought. This individual was a driving force behind the creation of the history exhibit in the neighborhood’s community center.

CRM historians entering Decatur and Silver Spring would get directed to these individuals from local preservationists and government officials. These are the same people and organizations who had erased the Black communities in these places.

Black history in Decatur and Silver Spring goes much deeper and wider than two individuals. Yet, historians don’t take the time to interrogate the power relations in communities and the complex ways history and historic preservation are produced in racialized spaces.

An alternative approach requires more time and training than the average CRM historian can draw upon. It requires genuine relationships with people in the community, relationships and a rapport built from trust. In racialized North America where the past is a commodity with different values attached to it, that trust is hard earned and sometimes impossible to obtain.

One summer day in 2018 I learned precisely how fraught public history and historic preservation are. I had heard from several sources over the years that many African American residents in Montgomery County, Maryland, would not talk to historians. Or, if they did, the conversations would be superficial, at best.

That day in 2018 I knocked on the door of a woman in an African American community established around the turn of the twentieth century. I explained why I was there (to ask about history) and she told me that she wasn’t interested in speaking.

You see, I was three historians too late. I asked her why. “Because I’m getting tired of everybody else profiting off of us,” she told me. As she was getting ready to close the door, I asked her if I could run a recorder while I asked her questions about why she didn’t want to talk to me about her community’s history. She agreed.

“I’m getting sick and tired of people coming here, all of a sudden now they want to know the history about the [the community],” she said. “They are profiting. I have yet to see anyone come back to me and say, ‘This is what I am planning on publishing. This is what you said.’”

The woman’s comments were underscored in a panel I attended at the 2018 American Folklore Society meeting in Buffalo, N.Y. A Louisiana folklorist recounted a conversation that she had with a colleague doing fieldwork in rural communities affected by storms and climate change. The communities had been overrun by historians, anthropologists, and journalists. One resident told the folklorist’s colleague that no one would speak with her because they are tired of being treated like an “extractive industry.”[iv]

So how are public historians supposed to get at the competing histories Carpini wrote about in an environment where history is a commodity and the past is a commons with an increasing number of enclosures encroaching on it? More to the point, as public historians discuss repair work at the conference this spring, how are we going to repair decades of bad history and historic preservation? It’s something that the people we seek to learn and write about recognize, but is it something we as public history professionals are ready to confront?

[i] Richard M. Hutchings, “Meeting the Shadow: Resource Management and the McDonaldization of Heritage Stewardship,” in Human-Centered Built Environment Heritage Preservation, ed. Jeremy C. Wells and Barry L. Stiefel (London: Routledge, 2018), 67–87.

[ii] James C. Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990).

[iii] David S. Rotenstein, “Decatur’s African American Historic Landscape,” Reflections 10, no. 3 (May 2012): 5–7.

[iv] Maida Owens, personal communication. I followed up with Owens by email after the meeting. “I was also stunned. I am not aware of this perspective being addressed in writing. Actually, I’m not sure how often it is used or by how many people,” she wrote.

~ David Rotenstein is a consulting historian and folklorist based in Silver Spring, Maryland. He researches and writes on historic preservation, industrial history, and gentrification.

After this post was published, Maida Owens wrote to me asking for a clarification regarding her comment quoted in note iv: “I think it would help to say that I am not aware of the term being used [in Louisiana].” Owens added in a second follow-up email to me, “I was referring to local usage, not the wider context.” Apologies if my note wasn’t clear.