Working with competing histories

29 January 2019 – Heather Lynn Carpini

Outbuildings at The Meadows, Abingdon, Virginia. Photo credit: Heather Lynn Carpini.

As historians working in the field, consultants often see value in objects, buildings, landscapes, and locations that may be overlooked by the general public. Living in a community, people can pass a place daily without knowing anything about its history. Or they may have heard the cursory basics—facts that tie it to a major person or event in the town or region. One of the most common refrains I hear when I’m working in communities is, “There is nothing here that’s historic.” In most cases, nothing could be further from the truth, but finding the overlooked history of a place requires reshaping public perceptions of what exactly constitutes history. Moreover, it entails digging deeper, past the obvious sources, into the lives of the people who shaped, and were shaped by, a certain place.

For communities that have multiple historical narratives, consultants face the challenge of teasing apart interwoven stories. Recognizing that together these stories have created the sense of place and history of a location, they must present them in a way such that each part is given credence. This can prove difficult, however, as “communities can dispossess elements of their local history from current memory,” as Jon E. Taylor writes in his study of Independence, Missouri, resulting in the sublimation of some aspects of their history to a dominant narrative.

During my work as a public historian, I have “found” the issues of competing history in various ways, including survey projects, mitigation projects, or public input/community engagement work. They have taken on many forms and each has presented its own unique set of challenges. How, as a consultant, do you get past the dominant historical narrative? How do you find “history” that people don’t believe exists? And when you find it, how do you balance it with present-day planning and growth? Some notable examples from recent work demonstrate these challenges.

Two survey projects I have worked on recently have resulted in the identification of significant historical resources at odds with the community’s view of its own history, as well as the need for development and growth in the area.

In Abingdon, Virginia, a historic early-twentieth-century “country house” and farm outbuildings, which were built on the site of an earlier plantation, were slated for development. The property was significant both architecturally and for its connection to early-twentieth-century dairy farming in the region; although local history sources indicated that there was a pre-Civil War plantation on the site, multiple archaeological investigations failed to uncover components of this earlier plantation occupation. Portions of the community, including the local government, supported the development and agreed to incorporate the significant residence into the plans as part of the mitigation; however, another faction of the town remained focused on the earlier plantation component, sought to use local lore surrounding the plantation to stop the development, and vilified the mitigation process. Although the property had been vacant and unused for years, any change to the property was contrary to their vision; preserving the physical portion of the property with no change, and therefore leaving it vacant and falling into disrepair, was the only acceptable option for them. In this case, we have tried to engage the dissenting faction as much as possible, so as to be inclusive of their information in the mitigation products. This has occurred with varying levels of success.

Tivoli Plantation, Orangeburg County, South Carolina. Photo credit: Heather Lynn Carpini.

In rural South Carolina, the development of solar power resources has come into conflict with a significant historic property, located directly across the street from the planned new development. In rural, former plantation areas with large expanses of unused or underutilized agricultural fields, large solar energy arrays are becoming a popular option for gaining return on investment in this open land. Unfortunately, many of these fields are in close proximity to historic rural resources that derive some of their significance from their agricultural surroundings and associated viewsheds. How do consultants balance the story of a historic resource with the local appeal of economic growth and opportunities, as well as the positive sentiment associated with “green energy” developments? A common refrain is that preservationists hinder progress, so what creative ways can we incorporate both the need to retain the history of a place with the growing desire to move forward?

One of the most complex instances of competing histories that I have encountered as a public historian is that of Independence, Missouri. On the surface, three major historical narratives have strong roots in the story of Independence: the starting point of Western expansion on the California, Oregon, and Santa Fe Trails; the early-1930s home of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Mormon) and later headquarters of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS) Church (now the Community of Christ); and the home town of President Harry S. Truman. Each of these stories represents a significant period, person, or series of events in American history. Interwoven with these narratives are also the stories of the businessmen who flourished because of the wagon trains stopping in the town, the early government of Jackson County, Missouri, the families who populated Independence because they never got further than the starting point of the trail system, the farmers and planters on the outskirts of the original town (now within the city limits) who played an integral role in Bleeding Kansas and the Civil War, the connections to Frank and Jesse James, the early-twentieth-century growth of the town, and a thriving African American community that was displaced by urban renewal. Any one of these contexts demonstrates the historical significance of places within the community, but in Independence, each one clamors for top billing and many of the newer narratives are lost among the infighting. In a city that argues over which history is important, yet has many who balk at preservationists because of infringement on personal or religious property rights, a public historian must tread a careful path.

Independence, Missouri’s 1827 Log Courthouse. Photo credit: Heather Lynn Carpini.

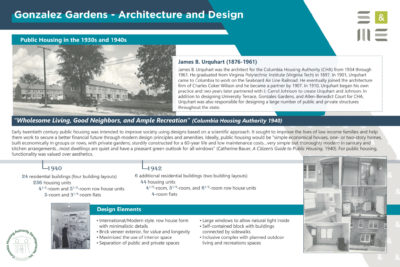

Finally, as part of a mitigation project for the demolition of a 1930s public housing project, I ran into two polar opposite views of government housing complexes. There is a very strong opinion about housing projects that the majority of the general public holds; it is informed most often by what they see on the news and read about in newspapers and online news sources. However, the people who have lived in these housing complexes have a very different viewpoint, which was developed over the time they spent in these government subsidized homes and the experiences they had there. When the demolition of the 80-year-old housing project was announced, the general public sentiment was relief and excitement, but many former residents felt sadness and a sense of nostalgia. Woven into these two perspectives is the history of public housing in the United States—its purpose, its funding, its planning, and its architecture. The buildings that remain are the physical manifestation of this history and the memories of former residents, which provide a rich context for the social history. These are the stories that much of the public doesn’t know and they wonder why preservationists are clamoring to document a public housing project, because the complex context of the resources isn’t always evident.

Telling the history of a 1930s public housing project. Photo credit: Heather Lynn Carpini.

In each of these instances, community engagement and tapping into local resources was the key to success. Although it may not always be easy to identify each of the competing viewpoints, listening to multiple players and taking their beliefs into consideration can help to give credence to each competing narrative. Humanizing the history by using oral sources to tell personal stories is a powerful tool, as is creating accessible and visually appealing resources that engage a community and help residents to think about the complexity of their history.

~ Heather Carpini is a senior historian/architectural historian with S&ME, an engineering firm that offers cultural resources consulting services based in Raleigh, North Carolina. She holds an M.A. in public history from the University of South Carolina.

This is an important essay. James Scott’s concept of “hidden transcripts” informs much of my thinking these days on these issues of competing history. So too does the classic, Silencing the Past. What I would like to see (and perhaps I may pitch to H@W) is a complementary essay on how our local sources are identified and evaluated. Since this essay is wrapped around cultural resources management, I’ll limit my observations to that context. CRM is an industry hamstrung by formulaic regulations and guidelines, tight budgets, and organizational pressures to make clients happy. Going deep into a community, especially if the researcher is based in an office 100 or more miles away, is part of the typical CRM project model. Fieldworkers have to quickly and economically identify sources (documentary and living) and then complete their scopes of work on time and under budget. That doesn’t leave a whole lot of time to critically read past histories, CRM documents, and planning documents. It also doesn’t provide for getting to know the people in a community to create essential rapport so that oral history/ethnography is meaningful.

For folks who have been following my work in the DC suburbs, this is abundantly clear with regard to the Talbot Avenue Bridge and the nearby Lyttonsville community (see https://ifph.hypotheses.org/2715 or https://forum.savingplaces.org/blogs/david-rotenstein/2018/12/26/an-old-bridge-speaks-about-race-and-history for a capsule introduction). Even when more of the bridge’s social history became widely known, consultants for the state failed to effectively resolve the adverse effects to the property. They stuck with minimal (and erroneous) state-level documentation (a completed survey form) and they only sought out one individual in the neighboring African American hamlet as a token informant. I use this word, “token,” cautiously and intentionally. Public historians working in CRM contexts all too easily reproduce tokenization found in grassroots and smaller-scale (municipal) historic preservation programs. They find one person (in this case, elderly African American woman) and that individual becomes the key informant driving the subsequent narratives and historic preservation products. If the CRM historian is enterprising, she will create a snowball sample of additional informants based on that first tokenized individual’s recommendations. It’s easy to do: I did it for decades while working in CRM. I would go to a community, visit the historical society, historic preservation planner (if there was one), and some of the other typical suspects and then I would be off to look for the people they recommend. If a community has an established track record of producing biased, incomplete, perhaps even downright racist histories, how do you think those recommendations will stand up within the community where the research is to be done?

The approach I described above isn’t enough and it only contributes to more bad history and poorly conceived historic preservation products. I have spent the past 7 years asking people how history is produced in their communities. The answers might shock many folks who believe that they are doing inclusive, thorough public history work. For example, take one woman who lives in Lyttonsville and who isn’t one of the tokenized residents. She is wary of all historians because with each new wave, they without exception always end up knocking on the doors of the same one or two people — not hers. The consequences are substantial, as I have learned in my interviews with her and others.

Or take the example I have written about here several times: Decatur, Ga. After visiting the newly completed African American history exhibits produced in the Beacon Municipal Center (see https://ncph.org/history-at-work/historic-preservation-shines-a-light/), several current and former Decatur residents (all of them African American) have sought me out by telephone and email because the history told in the exhibits is “all lies,” according to the handful whom I have interviewed in recent years. Those narratives were constructed by professional historians who tokenized the city’s Black residents.

The ways in which public historians work with local histories have profound impacts on people, buildings, and cultural landscapes. When we do it right, the benefits are manyfold. But when we do it wrong, the impacts become yet more social costs imposed on vulnerable people whose bodies and histories have been erased. I am glad this conversation is occurring.

I greatly appreciate this commentary. As someone who has worked in the CRM field for most of my career, I am often frustrated by the time and budget constraints associated with the majority of projects. I am acutely aware of the limitations that this type of public history has and my goal with this post was to hopefully begin a discussion on how we can do better history in these types of communities by identifying more sources and getting outside of the dominant narrative. For instance, I lean toward the thought that it is better to start the conversation by touching on the deeper history and acknowledging the limitations, and consequently the additional research opportunities, that exist…because if that step doesn’t happen, will the attention to these stories ever come. But, does that ultimately hurt the field of public history and hinder the work of future historians by creating a distrust or disdain for researchers among community members?

Mount-washington School comes to mind.