Editor’s Corner: Indigenous presence and memoryscsapes

01 May 2025 – Sarah H. Case

memory, The Public Historian, National Park Service, Confederate memorials, Editor's Corner, Indigenous People

Editors’ Note: We publish the editor’s introduction to the May 2025 issue of The Public Historian here. The entire issue is available online to National Council on Public History members and others with subscription access.

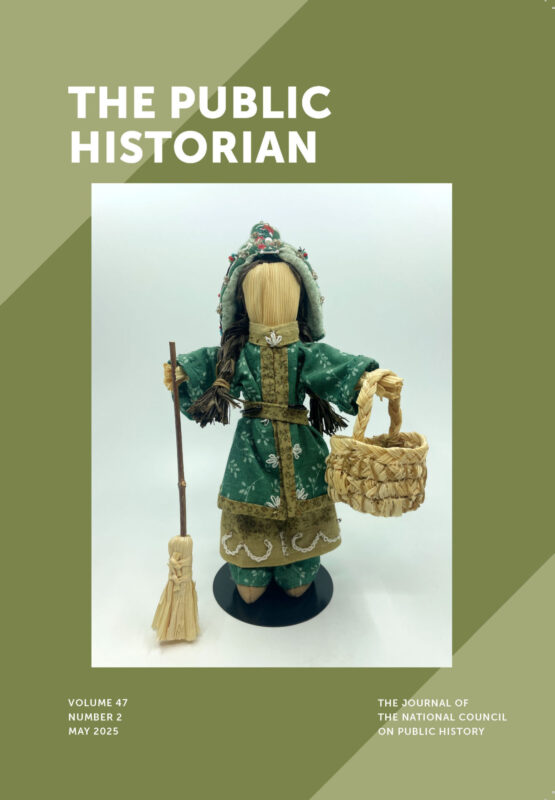

On the cover: Corn husk doll wearing hand-stitched calico by Anne Jennison. See “Deep History and Continuing Presence: Strawbery Banke Museum’s Abenaki Heritage Initiative,” co-authored by Jennison and Alexandra Martin, part of a special section on museums collaborating with Indigenous communities in this issue. Photo credit: Strawbery Banke Museum, 2019

This issue features two research articles and two reports from the field. The two articles both consider the meaning of representation and “memoryscapes” (physical spaces that shape understandings of both history and contemporary identity).

Thomas Rust’s “Silent Echoes: History, Ecology, and Yellowstone Park’s Colonial Memoryscape Through a Critical Examination of Wayside Signs” examines the underrepresentation of history, and particularly of Indigenous history, in the park’s educational signage. Surveying over 480 wayside signs in Yellowstone Park, Rust found that less than 2 percent examine Native American history (mostly discussing the Ni’imupu/Nez Perce) or the ongoing cultural significance of the area to Indigenous peoples. Rust argues that the “memoryscape” created by the National Park Service’s wayside signage presents a “muted understanding of Indigenous people’s history in the world’s first national park and their role in its ecological systems.” Although former Department of Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and the first Native American to serve in a cabinet position, made tribal consultation and inclusion of Indigenous voices a goal of her administration, much of that work moved slowly within the department’s large bureaucracy. Notably, under Haaland’s direction, the National Park Service increased its representation of Indigenous stories on its website, perhaps reflecting the relative ease of updating a website when compared to physical signage. Chillingly, however, much of that progress has been reversed—many of the hyperlinks cited in this article were dead or erased by March 2025 when reviewed before the issue was sent to press.

Our second research article, Ben Roy’s “A Spatiotemporal Examination of Confederate Monuments in the Former Confederacy,” uses statistical evidence to consider memoryscapes. Roy’s careful use of data produced by the Southern Poverty Law Center demonstrates a wider variation in region and across time in monument-building than studies that have focused on monuments to Confederate leaders such as Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis and on the 1890s through the First World War. Roy finds that most Confederate monuments honor the “common soldier” rather than a military or political leader, and that monuments continued to be built across the twentieth century—even well into the twenty-first. Although he acknowledges that more research is necessary before establishing a definite link between the two, Roy intriguingly notes regional variations both between and within states that seem to link increasing cotton production in the 1920s and 1930s with Confederate monument building.

The two Reports from the Field explore collaboration between museums and Indigenous communities. Although geographically far apart—one is in New Hampshire, the other in California—both museums offered exhibitions that would counter the colonial legacies of their institutions. To do so, curators at both institutions created a collaborative process that involved Indigenous partners’ participation from the start and foregrounded survivance (survival plus resistance) and the continuing presence of their people and communities. Interestingly, virtual programming created during the COVID-19 lockdown inspired programs that remain an important part of both museums’ outreach.

In “Deep History and Continuing Presence: Strawbery Banke Museum’s Abenaki Heritage Initiative,” co-authors Alexandra Martin and Anne Jennison examine Portsmouth, New Hampshire’s Strawbery Banke Museum. The museum is located in a collection of buildings across nearly nine acres of space and has traditionally interpreted several time periods at once but has given little attention to Indigenous people. Jennison, an educator of Abenaki heritage and Martin, an archaeologist at the museum first created educational programming at the museum focused on the Abenaki with Jennison present, demonstrating traditional arts, and later, a permanent exhibition, “People of the Dawnland” (2019). Working with others in their community, they later created an exhibition featuring work created by contemporary artists as well as archaeological objects. The exhibitions evolved into the Abenaki Heritage Initiative, which includes videos created during the pandemic shutdown, a reconstructed wigwam, a teaching garden, and educational programming.

Sarah FitzGerald, former curator at the Rancho Los Cerritos in Long Beach, California, worked with local Tongva community members from the start to develop our second Report from the Field, “Tevaaxa’nga (Te-vaah-ha-nga) to Today: Stories of the Tongva People.” Rancho Los Cerritos, constructed in 1844, has generally focused its interpretation on the wealthy landowners who ran the rancho. As the curator, FitzGerald created an exhibition centering the history and presence of the Tongva people. FitzGerald’s report is candid about the challenges she faced, including a lack both of funding and of Indigenous objects in the collection, a situation created in part by the museum’s focus on landowners. Additionally, FitzGerald acknowledges that one of the first challenges she faced was deciding which representatives of which local Indigenous communities to work with. Choosing to work with those who identified as Tongva, she found a positive collaboration and valued that they “ma[d]e decisions about the goals, parameters, structure, and approaches of the exhibition” throughout the process. As with the Strawbery Banke Museum, contemporary objects and oral histories underscored the presence of Indigenous communities in Long Beach and Southern California today. Further, the relationships extended well beyond the completion of the exhibition.

~Sarah H. Case, the editor of The Public Historian, earned her MA and Ph.D. in history at the University of California, Santa Barbara, where she is a continuing lecturer in history, teaching courses in public history, women’s history, and history of the South. She is the author of Leaders of Their Race: Educating Black and White Women in the New South (Illinois, 2017) and articles on women and education, reform, and commemoration.