James Oliver Horton: an appreciation

31 March 2017 – Denise Meringolo

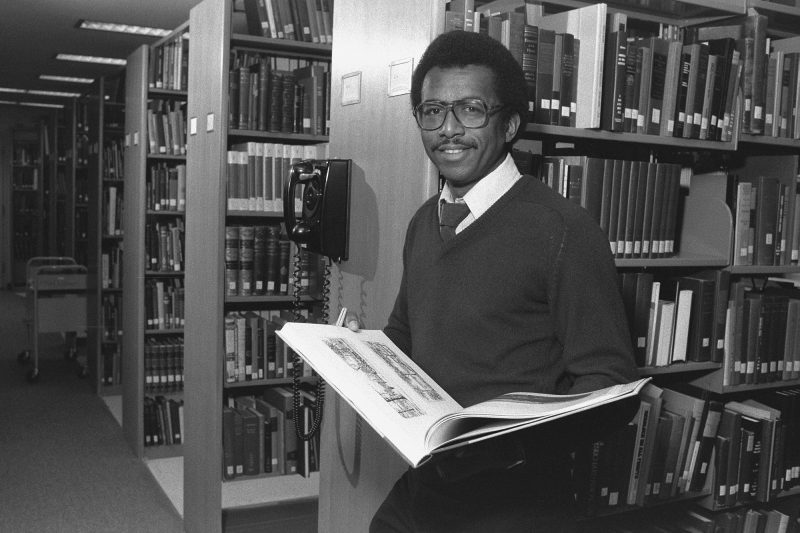

James O.Horton, 1982. Photo credit: Smithsonian Institution Archives

James Oliver Horton, emeritus professor of history and American Studies at the George Washington University, died on February 20, 2017 after a long illness.

Jim Horton was, at heart, a teacher. A former student, Dr. Laurel Clark Shire, recalled his tremendous faith that “all history, no matter how sophisticated or basic, could be presented to any audience.” He sought out opportunities to participate in education beyond the classroom. A skillful storyteller and a proud master of the intelligent sound bite, Jim began appearing on television very early in his career. By the 1990s, he was a fixture in documentary film and educational programming. His credits include short films like Voices of Glory, full-length documentaries like Looking for Lincoln, and multi-episode events like Slavery and the Making of America.

Trained at SUNY Buffalo (BA), the University of Hawai’i, Manoa (MA), and Brandeis (PhD), Jim Horton was an expert on African American history with a particular interest in free people of color in antebellum America. His published works include Black Bostonians, In Hope of Liberty, Free People of Color, Hard Road to Freedom, and Slavery and Public History: The Tough Stuff of American Memory. As a scholar and an educator alone, Jim will be remembered as among the most influential historians of his generation. But Jim was more than a scholar and an educator. His personality, habits of mind, and sense of mission drew him to public history. His work built a more stable bridge between academic and public historians.

James and Lois Horton. Photo credit: American Antiquarian Society

Jim Horton championed collaboration. His working partnership with his wife, Dr. Lois Horton, produced at least six co-authored volumes as well as several co-edited collections. Jim and Lois brought different disciplinary skill sets to bear on their projects. Jim credited Lois—trained in statistics, computer programming, and social policy—with having made him into a true social historian. Former student, Dr. Paul Gardullo, argues “their mutual respect and collaboration speaks to some of the best qualities of public history work,” and highlights the value of working across disciplinary boundaries.

Arguably, Jim Horton came to the work of public history through the Smithsonian. During the 1980s, he established a research unit in the National Museum of American History, the African American Communities Project. According to Lois, he was motivated at least in part by a desire to support his graduate students and expose them to public history as a viable career. But Jim quickly became, in the words of Susan Ferentinos, “a great defender of the interests of public historians.” In the early 1990s, as chair of the National Park Service Advisory Board, Jim toured National Parks to discuss history with rangers, interpreters, and superintendents. Dwight Pitcaithley, former chief historian of the National Park Service, respected Jim’s approach to this task: “At almost every meeting, Jim would begin by saying ‘I’m coming to you with my vast experience with the National Park Service. . . All two months of it.’ It got a good laugh and put people at ease, and it opened them up to hearing about how to anchor their stories solidly in the scholarship.”

Jim Horton’s efforts to improve public history in the National Park Service did not end with lectures and moral support. In 1994, he spearheaded the publication of Humanities and the National Parks: Adapting to Change, a report establishing guidelines to improve research and broaden public interest in park service history and archaeology. Before and after the report’s completion, Jim worked tirelessly to support park research. He was influential in establishing a cooperative agreement between the National Park Service and the Organization of American Historians. He convinced the Gilder Lehrman Institute and the Newberry Library to allow Park Service employees to participate in summer teacher institutes. In the words of Martin Blatt, a former regional director in the National Park Service, Jim’s efforts provided ‘intellectual cover’ for Park Service professionals working to improve site interpretation, particularly as it related to the history of slavery.

Jim Horton, 2010. Photo credit: American Civil War Sesquicentennial Commemoration in Virginia

Jim Horton’s ideas—and his compassion—continue to shape the broad field of public history. His former students hold influential positions in universities and cultural institutions across the country, and around the world. A significant percentage of the staff at the National Museum of African American History and Culture counts Jim as an influential teacher, mentor, and friend. Jim regularly reminded us, “African American history is American History.” He understood the power of stories and the importance of crafting an inclusive past. For his former student, Dr. Paul Gardullo, a curator at the NMAAHC, Jim’s legacy is deeply ingrained in every fiber of the museum. For Gardullo, African American History is Public History. He wrote, “I’m talking about the deep and long tradition of African Americans speaking outside of the centers of power to create spaces for truth telling, to build new archives, to find new voices and communicate with and to people ignored and disregarded with histories that have been suppressed, oppressed and neglected. Sometimes this lineage included scholars from the academy but for much of the history it has been peopled by ‘public historians’ of sorts, from Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass, to James Baldwin to Majora Carter to Bryan Stevenson etc. etc. I want to claim a lineage for them as public historians. Why shouldn’t we? Once we do that, we can both recognize the tremendous and incredibly unique contribution of Jim Horton, but also put him in a constellation of folks that reach backwards and forwards in a broader more powerful, potent, forceful movement.”

Those of us who have been directly influenced by James Oliver Horton can attest that he will remain at the center of that constellation.

∼ Denise D. Meringolo is associate professor of history and director of public history at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Author’s Note: Thank you to Stephanie Batiste, Spencer Crew, Paul Gardullo, Lois Horton, David Kieran, Michele Gates Moresi, Dwight Pitcaithley, Kevin Strait, Laurel Clark Shire and others who spoke to me formally or informally as I prepared this appreciation.

Jim Horton’s deep and profound contribution to American history enriched so many exhibitions and public humanities projects. It was an honor to learn from him during my time at the National Endowment for the Humanities, and to continue to follow his seminal work as a museum director. He was a great communicator who understood the challenges — and the potential — of working on the front lines of public history in museums, historical societies, and national parks. He will be missed.

Jim Horton was a consultant for the Walt Disney Company when it tried to build Disney’s America three miles from Manassas National Battlefield Park. I interviewed him about his role, after Disney dropped the project. He said that Disney is an excellent storyteller and can draw way more people to history than us historians could ever do. So, by having him help guide Disney in making that history accurate and provocative, he was all for the project.