The making of James Madison’s Montpelier’s “The Mere Distinction of Colour” Q&A: Part 2

01 February 2019 – editors

slavery, methods, public engagement, community history, sense of place, TPH 40.4, collaboration, MDOC Q&A, museums, Montpelier, scholarship, race, The Public Historian

Editor’s Note: Want to know more about what it takes to develop an award-winning exhibition about the lives of enslaved people at a founding father’s historic site? We did, too! In this series, we will learn more about what went into the new permanent exhibition The Mere Distinction of Colour (MDOC) at James Madison’s Montpelier (JMM) in Virginia. The exhibition won NCPH’s 2018 Outstanding Public History Project Award and featured collaboration with descendants of slaves who identify with the JMM community. To learn more about the exhibition, be sure to check out the review by Megan Taylor-Shockley, published in the November edition of The Public Historian and provided generously by University of California Press for free for a limited time. Questions for this series were developed by the H@W lead editors as well as lead editor Will Walker’s students at The Cooperstown Graduate Program. JMM staff and MDOC collaborators took the time to provide in-depth, thought-provoking answers. We are publishing this conversation as a multi-part series highlighting topics ranging from exhibition development and design to working with descendant communities. This is a new feature that integrates NCPH’s print and digital publications. Let us know what you think! Questions and responses have been edited for clarity and brevity.

You can find PART 1 of this series here.

Part 2: Exhibition content

H@W Editors: Of course, it’s not possible to make history relevant to modern audiences without a solid foundation of rich, place-based, historical research. What did the research process for this exhibition involve? What kinds of sources did you use to tell this important story?

James Madison’s Montpelier staff mounting archaeological artifacts inside “The Mere Distinction of Colour” exhibition. Photo credit: James Madison’s Montpelier

Hilarie M. Hicks, Senior Research Historian, JMM: The exhibition has two distinct sections—one telling a national story and the other a Montpelier-specific story—and each required a different type of research. For the national section, the research team relied on the scholarship of others to get ourselves quickly up to speed on the history of slavery in all parts of the country.

For the Montpelier section, it was virtually all primary-source research. For many years, we had been building a body of research materials on the enslaved community, accessible through our Montpelier Research Database. Yet we still tended to fall into the trap of focusing on all the things we didn’t know. In one of the early stakeholder discussions, a descendant told us to focus on what we did know, and as obvious as that seems now, it really led to a paradigm shift in our thinking. We realized we didn’t have to nail down an enslaved person’s entire life story to be able to talk about a particular moment of that person’s life as revealed in a document.

This played out as we pulled research together for an interactive map, showing places on the national, state, local, and plantation levels that we can connect with someone from the Montpelier enslaved community. For example, using a daybook from a local store, we can point to the place where on October 23, 1785, Jack bought 8 ½ yards of cloth, 3 yards of ribbon, one dozen buttons, thread, a thimble, one dozen pipes, and two quarts of rum. A slave pass lets us plot Benjamin McDaniel’s June 1843 trip to Dr. Henkal in New Market, Virginia. Marking Louisiana on the map helps us visualize the trip made by 16 enslaved laborers sold by Madison to a cousin starting a sugar plantation. Madison’s letters tell us about Betty, whose sale price was reduced because of her health. Taken together, the primary sources connected to the interactive map tell the story of an entire community, even when we may know only one or two facts about each person mentioned.

H@W Editors: We know Montpelier boasts an active archaeology program. What role did archaeological projects and findings play in your exhibition planning?

Matt Reeves, Director of Archaeology & Landscape Restoration, JMM: Archaeology of the homes of the enslaved community provided the evidence for us to understand where these buildings were located and what they looked like and also to give JMM the ability to recognize just how integrally the enslaved community was tied to this historic place. Pursuing archaeology at Montpelier helped us develop much more than a simple understanding of what kind of ceramic dishes slaves had, or the appearance of their home. Descendants started asking questions of artifacts being uncovered that we never thought to ask. One of the most challenging questions was what these artifacts—such as a pipe that bore the word “Liberty”—represented for their ancestors. What did an enslaved person who was smoking that pipe and who was owned by the man that devised the ideals of the Constitution think about the meaning of liberty?

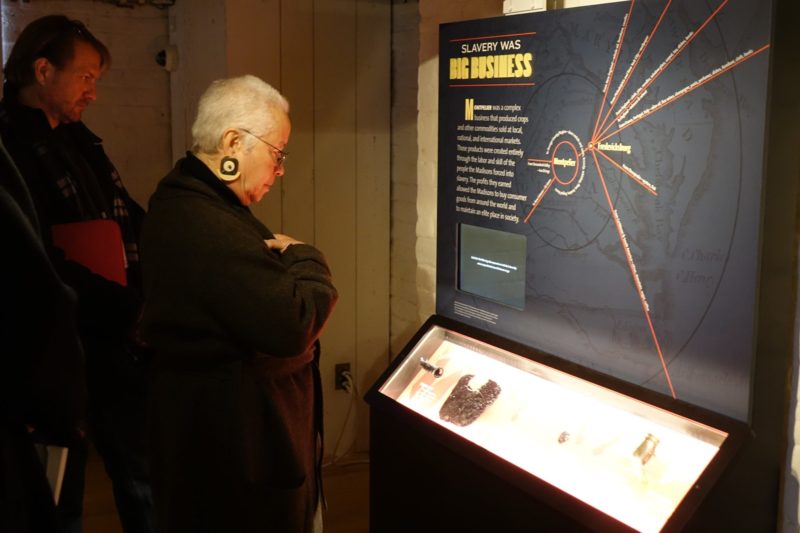

National Summit on Teaching Slavery participants learning about the business of slavery inside “The Mere Distinction of Colour” exhibition at James Madison’s Montpelier. Photo credit: James Madison’s Montpelier

H@W Editors: MDOC features a variety of ways to present the content. Can you give us an example of how you presented historic content using contemporary people or tools?

Hilarie M. Hicks, Senior Research Historian, JMM: For the Stewart family, we were able to piece together a remarkable story. Research associate Lydia Neuroth pulled together documentary evidence about the sons and daughters of Sukey (Dolley’s lady’s maid), including letters between Dolley and her stepson, letters written by Benjamin and Sarah Stewart, and articles from abolitionist newspapers (published online in the Dolley Madison Digital Edition). Elizabeth Ladner, who was then director of research, did extensive genealogical research to trace Sukey’s daughter, Ellen. For instance, Ladner connected her to an early twentieth-century cookbook to which Ellen contributed a recipe, as “Dolley Madison’s cook,” under her married name. I wrote up the research in narrative form and then we gave it to African American storyteller Sheila Arnold. In turn, Arnold scripted the story in Ellen’s voice for what became the powerful video “Fate in the Balance,” which can be seen in the exhibition.

H@W Editors: Since MDOC opened, have you identified new artifacts related to the stories you are telling that you have incorporated or plan to incorporate into the exhibition? How will you keep the exhibition fresh and exciting?

Christian Cotz, Director of Education & Visitor Engagement, JMM: Our archaeology excavations are never ending, so we are constantly pulling new artifacts out of the ground that illustrate this story. We also plan to expand the exhibition into two buildings that have yet to be built in the South Yard: a late eighteenth-century spinning house/slave quarter and a kitchen that began its life as Madison’s boyhood home in the 1750s. These two buildings should be completed in spring of 2019 and spring of 2020, respectively.

In addition, we’ve already completed a conceptual design for exhibit components in the spinning house that will be aimed at our youngest visitors. These interactive components will use conceptual themes of injustice, fairness, and race as foundational building blocks to nurture children’s empathy toward the enslaved when they are confronted with that difficult history later in their learning trajectory and will foster the same sentiment toward the people around them in their daily lives.

Third, the boyhood home will likely be furnished to its appearance as a late-1820s detached kitchen, as that is the era in which we furnish and interpret the rest of the spaces in the historic core of the property. We intend the kitchen to be functional and hope to have demonstrations and workshops there. We will also interpret personal stories, as we have done elsewhere in the South Yard, specifically drawing on the oral history of descendant Bettye Kearse, whose ancestor Coreen was one of the Madison family’s enslaved cooks.

Finally, in the far-off future, we have aspirations of excavating and reconstructing an overseer’s house and interpreting there the dynamic intersection of class, race, and power that led to the rise of modern racism in American society.

Editors’ Note: In this MDOC Q&A post, we started to learn more about the role descendants played in shaping MDOC and the interpretation of slavery more broadly at JMM. In the next post, we will delve even more deeply into the nature of descendant involvement at JMM.