Reflecting on the first NCPH “extraordinary service” award

18 May 2018 – Cathy Stanton

Cathy Stanton leads the NCPH’s Digital Media Group in Nashville in 2015. Photo credit: Amy Tyson

Editor’s note: this is the second in a series of pieces by recipients of NCPH’s 2018 best in public history awards.

On learning that I would be receiving an award for “extraordinary service” to the National Council on Public History, my initial response was to point out that the projects I’ve been involved in have always been group efforts by staff and many other NCPH members. But conversations with thoughtful friends and colleagues have helped me see why the particular ingredients I added to the mix may have been valuable at this particular moment in the life of the organization. And so I’d like to reflect on that briefly, with the subtext of encouraging others to find ways of getting more involved even if it’s not quite clear yet where your own talents and questions might fit.

When I attended my first NCPH conference, in 1999, it immediately seemed to me that public history was a field where an anthropologist (which I was learning to be) could be engaged as both a participant and an observer (which is what anthropologists do). As a graduate student with an interest in commemorative behavior, I was excited to discover a whole community of people both working in and studying sites where the past was being put to use.

At that conference, Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen gave a plenary presentation on their recently-published book The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life. I remember being struck by Thelen’s admission during the Q&A that as historians, they found themselves not quite sure what their next steps might be now that they had collected and collated their massive body of data. “This field needs more anthropologists!” was my immediate reaction.

A few years later, when I presented some preliminary results from my own ethnographic exploration of how public history had contributed to the economic redevelopment of a former industrial city, Rebecca Conard commented that my data about the close racial and class alignments between public historians and their visitors was important information. “If we’re only talking to people like ourselves, we need to start doing something different,” she insisted. It seemed that an anthropological perspective—concerned with both margins and centers and always attentive to the workings of power—did indeed have value in holding a reflective surface up to what public historians were doing.

Public history itself often seems to have far more margins than centers. But within this wide space of porous boundaries, the National Council on Public History does serve as one important connecting-point. As a small, nimble, and young-but-not-brand-new organization, NCPH was just entering a maturing phase of its existence when I became involved with its digital projects in 2005.

Under the leadership of John Dichtl and now Stephanie Rowe, NCPH has retained its nimbleness as well as its position at the intersection of public history practice, education, and scholarship. That can be surprisingly uneasy territory, and I think it’s where the newly-emerging digital tools of the mid-aughts served us particularly well. We were able to start linking together existing and newer forms—listservs and blogs, scholarly publication and social media—in a way that has created both continuities and new openings to what’s happening on those many margins. We did this on less than a shoestring budget, starting with out-of-the-box platforms (our first conference blogs, starting in 2008, were on Blogger) and then relying on help from our friends at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media as we began to assemble a digital ecosystem that could serve many functions and audiences.

As our digital projects developed, my role was very often to be the one attempting to explain to the wider membership what we were trying to do, even as staff and members of NCPH’s Digital Media Group were trying to figure that out for ourselves. I particularly remember one muggy summer meeting with our partners at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities at Rutgers University-Camden when a group of us spent two days trying to “think together” all of the various pieces of what we’d been building—this blog and its volunteer editorial team, our social media networks, the relationship between NCPH and The Public Historian journal, and the badly-outdated NCPH website.

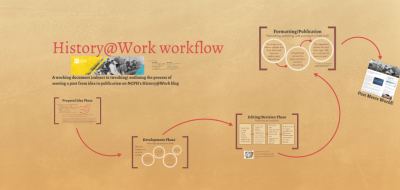

Before stepping down from her role as volunteer Digital Media Editor, Cathy posted this helpful Prezi about the History@Work workflow. Prezi: Cathy Stanton

It was a surprisingly mind-bending exercise, but it helped us move toward a more unified sense of how those components fit together and how we might host and archive everything within a single digital space. Once our new WordPress-based site debuted in early 2016, I started moving away from what had become a too-unwieldy set of editorial roles, now redistributed among editors and staff at NCPH, The Public Historian, and the Digital Media Group. It’s wonderful to see this network continuing to grow stronger.

Although my involvement in NCPH has centered mostly around digital projects, one of the things I’ve most enjoyed about it is that it was never just about digital projects. The larger goal was always to build tools that would serve a maturing and expanding organization with a rapidly-growing conference in a field that was also growing quickly, to the point that some were starting to question its sustainability as well as how it could best contribute to an increasingly urgent set of issues in the civic realm.

It’s been a privilege to play a role in creating places for those discussions, to take part in them, and occasionally to help nudge them along. I’m grateful and humbled to have received such a generous tribute from the organization that has become my professional home. And I’m paying close attention to the new questions and perspectives that are emerging and gaining purchase around the edges of a field that only seems more relevant and important with every passing year.

~ Cathy Stanton is a senior lecturer in the department of anthropology at Tufts University and an active public historian. With Michelle Moon, she is the co-author of Public History and the Food Movement: Adding the Missing Ingredient (Routledge, 2018).