“What Could It Have [Been] Then?”: Reflecting on the origins and historiography of a plantation historic site

12 May 2020 – Noah Janis

African American history, public engagement, plantation, community history, North Carolina, interpretation, race, slavery, historic preservation, commemoration

A big house. Stately trees. Curious outbuildings. In 1905, Pennsylvania-born tourist Matilda Kessinger marveled at the landscape before her, “something one always reads about but never sees.” After 18 years of traveling the South, Kessinger had finally found the one place that lived up to her romantic ideals of an antebellum plantation. Yet she still had a nagging feeling that something was missing. As Kessinger recalled in a letter to the Mifflinburg Telegraph, “A lady told me this morning, that had visited this place before the war, that it seemed nothing but a wreck now. What could it have [been] then?” Twenty-first-century visitors to Somerset Place, now a North Carolina Historic site, also recognize that Somerset’s history is expansive and layered. But instead of asking, “What could it have [been] then?,” guests also want to know, “Why did it change?”

Two early 20th-century visitors stand in front of original slave dwellings at Somerset Place. The plantation home is in the background. Photo credit: State Archives of North Carolina

Somerset Place was one of the largest antebellum plantations in North Carolina. From 1785 to 1865, over 861 enslaved persons, two free black employees, and more than 50 white employees lived and worked on the plantation under three generations of the Collins family. A tiny fraction of the original Somerset Place has been preserved as a state historic site. Through a comprehensive guided tour of original structures in the owner’s compound and reconstructed buildings in the enslaved community, we interpret the lives of all of the plantation’s residents.

Much of the tour focuses on the 1840s because of the extant structures, detailed primary sources, and major events that affected every family associated with that period. Yet we only have so much time to cover 80 years of history, which prompts frequent questions from visitors about what happened next. Was the plantation abandoned after the Civil War? How are these buildings still standing?

As we set out to develop a comprehensive response to these frequently asked questions regarding the plantation after the Civil War, we were also approaching Somerset Place’s 50th anniversary as a state historic site. So, we decided that the best way to commemorate our jubilee was to address our post-war history with a special guided tour about Somerset Place from 1865 to present.

As I sat down to create this new tour, I knew the trail had been blazed before me, because substantial research into our last 150 years of history has already been conducted by generations of historians. The sheer quantity of source material about this period prevented us from covering it all. So, the challenge was condensing all this information into a cohesive, engaging, 75-minute narrative.

Tackling all the nuances of 150 years of history in an absolute chronological order would not be feasible. We are not here to lecture visitors; we are here to engage them in a conversation. I divided the information thematically as much as possible, including stops focusing on formerly enslaved persons pursuing their freedom, and the changes in the built environment.

But having information to talk about on the tour was one thing. Where to go and what to see on this tour was another. How could guests visualize the last 150 years of history when everything they see has been restored to its appearance around 1840? The answer was two-fold: conceptualize the site from different angles, and use handouts to illustrate what could not be seen.

In August 1938, a visitor poses in front of the plantation’s four-story barn, which burned eleven years later. We use this photo on the tour as one of our primary source hand-outs to illustrate changes in the built environment. Photo credit: State Archives of North Carolina

Instead of following the standard tour route, we traverse pathways and roadbeds that allow visitors to see the transformation of the site from various perspectives across space and time. From inside a reconstructed slave dwelling, we consider the community of enslaved people. Going along the row of archaeological foundations we visualize the changing landscape. We consider the site’s early romanticized interpretations along the tree-lined drive to the plantation house. We then supplement this visualization of our site’s layered history with primary source hand-outs and illustrations.

Having research, themes, and routes in hand, my colleagues and I crafted a tour of honest reflection. We cover the demise of slavery, the period after the Collins family’s ownership, and the lives of newly freed African Americans from the plantation. We also discuss how Somerset Place was preserved as a public site and how memories and interpretations of its history changed from the Jim Crow-era to the present.

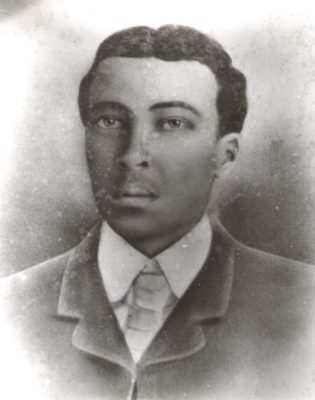

Ransom Bennett, Sr., (1842-1916), who was born into slavery at Somerset Place, was the first constable of Creswell, North Carolina. Photo credit: Dorothy Spruill Redford, Generations of Somerset Place: From Slavery to Freedom (Charleston: Arcadia, 2005).

During the tour, we meet fascinating residents, visitors, and researchers, including Ransom Bennett, Sr., who was formerly enslaved at Somerset Place and later served as the first constable of nearby Creswell, North Carolina, less than a decade after emancipation. We also meet Dorothy Spruill Redford, a woman who changed the narrative at our historic site by researching the enslaved community, which included her ancestors, and organizing a reunion of over 2,000 descendants of the enslaved, and the enslavers. This reunion, known as the Somerset Homecoming, was held in 1986 to mark the 200th anniversary of the arrival of 80 enslaved Africans to the plantation.

Her work not only transformed the interpretations at Somerset Place, but also marked a shift in interpreting slavery at plantation sites across the country, some of which has been featured on History@Work. Each person who lived, worked, or was involved with Somerset Place from 1865 to the present has had an impact on where we are as a site in 2020.

Descendants of the enslaved community reunite at the first Somerset Homecoming in 1986. Photo credit: North Carolina State Historic Sites

As we enter a new decade, the tide of historical tourism is changing. Visitors want to be part of inclusive sites, ones that share honest, unvarnished, and diverse history. Somerset Place has been at the forefront of this movement for decades, but other organizations, like Historic Stagville State Historic Site, have also helped shift the narrative by researching and interpreting the lives of enslaved African Americans and their descendants. To mark the 150th anniversary of nearby Durham, North Carolina, where many formerly enslaved people moved after emancipation, Historic Stagville presented a tour highlighting its connections with the city. We hope that with our new tour, more institutions will reflect on their recent histories so that the public can uncover the layers of our historiography together.

Somerset Place in the New South: From Plantation to State Historic Site, 1865 – Present, is offered on the third Saturday of every month at 1:00 p.m. or by reservation for groups of 15 or more. There is a tour fee of $3.00 per person. Please check our Facebook page for the latest updates on the impacts of COVID-19.

~ Noah Janis is a historical interpreter at Somerset Place State Historic Site. He is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he received his bachelor’s in history with a concentration in United States history.