Public historians as editors, editors as public historians

22 September 2022 – Constance Schulz

Professor Constance Schulz and three USC public history students at Housesteads Fort, during a visit to Hadrian’s Wall with the regional Inspector of Ancient Monuments as part of the England Field School in 2004. Photo credit: Lynn Robertson/Anna Kuntz

Editors’ Note: This post is part of a series of reflections from winners of NCPH awards in 2022. Constance Schulz is the winner of the Robert Kelley Memorial Award which honors achievements in making history relevant to individuals outside academia.

What does it mean to have spent a professional lifetime as a public historian? How did I—like many others who entered the history profession half a century ago—discover public history in the first place? The answer? Accepting the invaluable guidance of mentors and seizing unexpected opportunities.

My public history story begins with my first post-PhD position in 1973. Louis Harlan, my friend and mentor who directed my 1966 University of Cincinnati MA thesis, scolded me that spring, almost in jest, not to just hang my new degree on the wall. I was living in Baltimore where my husband, Carl, was completing a post-doctoral appointment at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and I had three children under the age of six. Louis invited me to join the staff of the Papers of Booker T. Washington (BTW Papers) part-time that summer as a research assistant, using the resources of the Library of Congress (LOC) to identify the often-obscure Black southerners who wrote to Booker T. Washington requesting help. Little did I know I was becoming a public historian as an editor!

During the next fifty years, first as an independent scholar and part-time evening and weekend adjunct faculty member in the Washington DC area, then as a National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) fellow at the Documentary History of the First Federal Congress, staff at the Smithsonian, the National Archives, the National Park Service, and the LOC encouraged me through informal meetings and networks of public historians. Through the University of Maryland Early American Seminar, I learned about the work that Lois Green Carr and Lorena Walsh were doing at the Maryland Hall of Records and Saint Mary’s City. Edie Mayo and Heather Huyck welcomed me to the “Friday Lunch Bunch” [a.k.a. Washington Women Historians] monthly gatherings of women historians working in Washington’s wide network of government history offices. I attended an early meeting of the National “Council” of public historians—possibly at the AHA offices, hosted by Arnita Jones—and learned of the work of “history for hire” consulting firms. Ray Smock, whom I had met at the BTW Papers, invited me to bring my early national U.S. history knowledge to the team he headed that was then creating the American History Slide Collection, introducing me to the pleasures of research in visual materials and the staff at the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division.

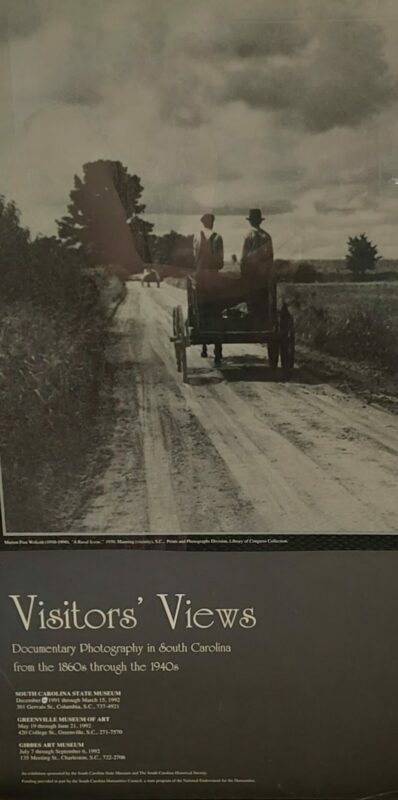

These experiences led to my being qualified to be chosen in 1985 as a faculty member at the “Applied History” MA program at the University of South Carolina (USC). There I finally became a full-fledged and self-aware public historian, immersed by necessity in another aspect of public history work: local history. The growing USC MA and MA/MLIS Applied (later Public) History program relied on state and local cultural organizations for student part-time jobs and internships. Many of their staff were graduates of the USC program. They became important contributors to my understanding of the general and the particular of SC history, and my partners in educating our public-historians-in-training as well as mentors to our students. The interest of South Carolinians in their state and local history led to some wonderful opportunities to expand my own experiences in public history, first as a grant writer to the SC Humanities Council for funding to create a “History of South Carolina Slide Collection,” and then as a guest curator with the South Carolina State Museum for a photographic exhibit, Visitors’ Views.

Poster promoting the South Carolina State Museum 1991-1992 exhibit “Visitors Views,” featuring photography of the state between 1850 and 1946. Image credit: South Carolina State Museum

Throughout all of this, NCPH as an organization and its members were a crucial part of my network of public history mentors. My students and I tried every year to attend NCPH and SAA meetings if possible—often using my faculty travel allowance to hire a van! Enthusiastic road trips to Washington, DC, Toledo, Ohio, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and Lowell, Massachusetts—and a memorable drive from SC to the SAA meeting in Montreal—allowed students to meet and come to know leaders in the public history field. Through the welcome that NCPH has given to public historians in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe, I came to know international practitioners and academic scholars. I was privileged to be able to assist Arnita Jones in drafting the bylaws for the newly formed International Federation for Public History (IFPH-FIHP) and to attend the Comité International des Sciences Historiques (CISH) – International Committee of Historical Sciences (ICHS) conference in China in 2015. My students have benefited from these international connections too. For twenty years, starting in 1990, I ran an “England Field School.” Through a month-long residence at Lord Baltimore’s 1625 Kiplin Hall home in North Yorkshire, I introduced students to hands-on practice of public and local history in another country.

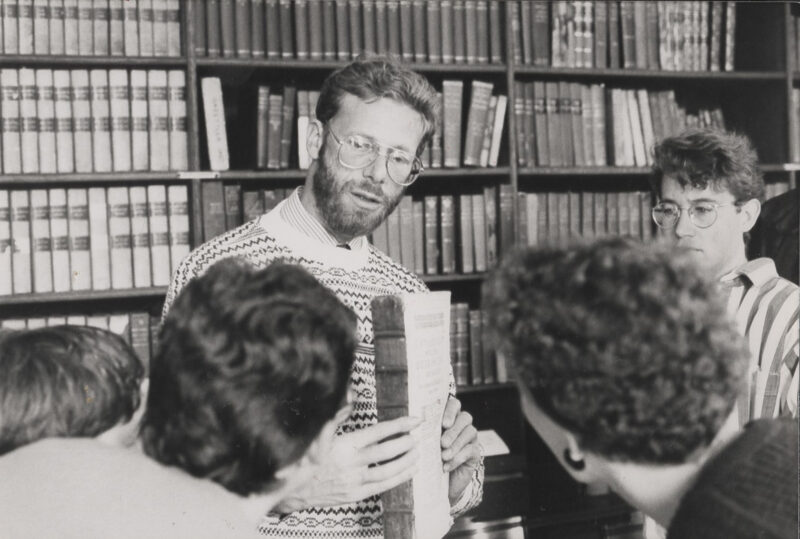

British Library conservation specialist Ed King explains to USC 1990 public history students preservation issues at the Kiplin Hall nineteenth-century library wing and its collections. Photo credit: Constance M. Schultz

As I did other things within the public history umbrella, I often connected the different areas of practice in public history to one another through the processes, values, and standards I learned as an editor, and the practice and love of historical scholarly editing have remained central to my career. For the past fourteen years since my official “retirement” as a teaching faculty member, I have had the privilege of returning to my roots, editing the papers of the Revolutionary and early national-era Pinckney family—first the women’s documents, and now those of the men. Again, it has been the support of members of the extended editorial public history community that enabled those projects to win National Endowment for the Humanities and NHPRC grants.

The lesson I hope that readers of this blog will draw from all of this personal history is that mentors matter. “Pass it on” should be a mantra for both more senior and younger public history professionals: mentor others and accept and appreciate the mentoring you yourself receive. And of course, don’t be shy about taking advantage of opportunities some of those supportive colleagues offer you in the process.

~Constance B. Schulz is a Distinguished Professor Emerita at the University of South Carolina, where she directed or co-directed the history department’s award-winning public history program from 1985 until her retirement in 2008. She published a number of books examining the FSA/OWI photography for individual states, and since 2008 has been the senior editor of the Pinckney Papers Projects, born-digital scholarly editions of the documents of the Revolutionary-era South Carolina Pinckney family.