Practicing public history through halls of fame

20 October 2020 – Kimberly Voss

Marie Anderson. Photo credit: National Women & Media Collection

After decades of being overlooked, Marie Anderson was inducted into the Florida Journalism Hall of Fame at the end of July. For more than two decades, Anderson was one of the most powerful women in Miami. During the 1950s and 1960s, as a significant club woman and the women’s page editor of the Miami Herald, she was well known in the city—and across the state. Yet, she was largely forgotten in her native state after her retirement in the early 1970s.

As an indication of her expertise, Anderson’s section won so many Penney-Missouri Awards—the top recognition for the sections at the time—that she was retired from the competition. She was known for introducing hard news topics into her section including the need for daycare, abortion rights, and equal pay. She became a regular speaker for newspapers across the country who wanted to improve women’s page news.

It seems strange that someone whose work was read by thousands for more than two decades could be forgotten. However, it is very difficult to learn much about women’s page journalists. Historians of journalism have often marginalized women like Anderson by their focus on the front pages, political columnists, and sports reporters. As journalists face layoffs and retirements and institutional memory is lost, recognition through halls of fame helps right this historical wrong.

Journalism halls of fame often mirror the histories which have typically recorded the stories of white male journalists. Often left in the margins are women and people of color who made a difference in their time. Nominating such journalists to halls of fame raises public awareness about their work. This is especially important for state and regional halls. Historian Eileen M. Wirth wrote that local history needs to be included in the study of female journalists as they rarely had national prominence. “We cannot understand the history of women in the United States unless we consider local and regional dimensions,” she wrote.[1]

Halls of fame have been around for more than a century. No one knows for sure exactly how many halls of fame there are in the U.S. They honor everything from astronauts to crop dusters.[2] In professional industries, halls of fame are about establishing whose stories get told. In the contemporary world, most halls of fame exist virtually, as publicly accessible websites.

Typically, journalism halls of fame began as parts of city or state press clubs. For example, the Chicago Press Club was established in 1880 to develop contacts between journalists and local leaders.[3] By 1919, press clubs existed in most major American cities and served both professional and social roles. These clubs often excluded women, who in turn established women-only press clubs, as historians Maurine Beasley [4] and Elizabeth Burt[5] have documented. Over the years, several women journalists attempted to join men’s press clubs but were unsuccessful.[6]

Many of these women remembered their exclusion. Fashion editor Aileen Ryan, who retired in 1967 after nearly 50 years at the Milwaukee Journal, was nominated for the Milwaukee Press Club Hall of Fame in 1981. Ryan, however, rejected the honor because she had not been allowed to become a club member during her career. Ryan later relented and in 1987, she was nominated again and became a member of the Hall of Fame

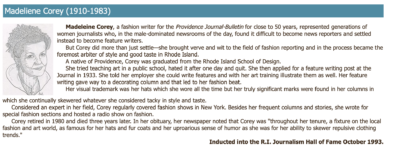

Membership in these journalism halls of fame allows the overlooked women journalists to become a part of public memory. For example, in my research about newspaper fashion editors, it was difficult to find much material about Madeleine Corey. Her name was often mentioned in news stories about fashion shows but there was not much more in the historical record. Luckily, her state’s journalism hall of fame provides details about her career.

Screenshot of the Madeleine Corey entry, Rhode Island Journalism Hall of Fame, 1993.

Two other examples of women’s page journalists I have successfully nominated to state journalism halls of fame are Marjorie Paxson (1923-2017) and Roberta Applegate (1919-1990), though the process was not easy. Both took repeated nominations before gaining entrance and required extensive archival documentation to demonstrate their significance.

Paxson was a pioneering journalist who covered hard news for a wire service during World War II before being forced back into the women’s pages after the war. The women’s pages began in most American newspapers in the late 1880s and were eliminated by the early 1970s.[7] In the first half of the twentieth century, the content largely focused on the home— furnishings, clothing, and cooking. In her women’s page position, Paxson helped change the definition of women’s news by focusing on stories in the public sphere. By the time she retired from journalism more than five decades later, she was one of the first woman U.S. newspaper executives and established the National Women and Media Collection (NWMC) archive held by the State Historical Society of Missouri at the University of Missouri.

Paxson was the fourth woman publisher in the Gannett newspaper chain, first at the Public Opinion in Pennsylvania and then the Muskogee Phoenix. At the Phoenix, she used her influence to change her publication’s editorial stance from opposition to support of the Equal Rights Amendment. She also changed the newsroom policy to allow women to wear pants—something that had been prohibited until 1980. She made a difference for female employees and women in her community.

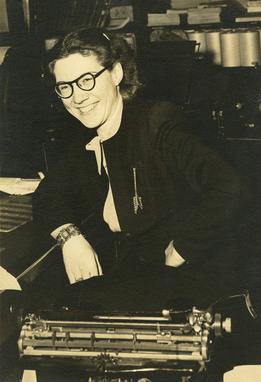

Marjorie Paxson. Photo credit: National Women & Media Collection

Despite the many accomplishments during her journalism career, she was not a member of the Oklahoma Journalism Hall of Fame, which I sought to change. It took five years to get her inducted. She would have been officially inducted posthumously in March 2020, but the ceremony was postponed due to COVID-19. She will be honored at a later date.

Several years ago, I successfully nominated women’s page editor, and later a Kansas State University journalism professor, Roberta Applegate into the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame. After earning a master’s degree in journalism, Applegate covered the Michigan statehouse during World War II and went on to become one of the first women to be a press secretary to a governor. It took two nomination attempts to get Roberta inducted. Part of the process was to submit numerous letters of recommendation, which was no easy feat considering that she died more than thirty years ago. Luckily, she saved her papers, and her collection at the NWMC included letters of reference from decades before. Along with her brother, I had the honor to speak at her induction ceremony. When Roberta was finally admitted into the Michigan Journalism Hall of Fame, it marked the first father-daughter combination in the hall. Her father, Albert A. Applegate, a well-known journalism professor at Michigan State University, had been inducted years earlier.

I will soon be turning in the nomination paperwork for Dorothy Jurney, known as the “godmother of the women’s pages.” Her papers are also at the NWMC. If you know of a woman or person of color who is a part of local journalism lore but has been left out of the historical record, consider engaging in an act of public history and nominate him or her to the state journalism hall of fame. It will be worth it for the contribution to public history and documenting the stories of people who have often been forgotten.

~Kimberly Voss is a full professor at the University of Central Florida where she teaches journalism history. She has published four books about women and mass communication. Her articles about women and journalism history appear in publications including American Journalism, Journalism History , and Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly.

[1] Eileen M. Wirth, From Society Pages to Front Pages: Nebraska Women in Journalism (Bison Books, 2013), 164.

[2] Richard Rubin, “The Mall of Fame,” The Atlantic, July 1997.

[3] Katherine Lanpher, “The Boys at the Club: An Examination of Press Clubs as an Aspect of the Occupational Culture of the Late 19th Century Journalist,” presented at the Association for Education in Journalism, History Division, Athens, Ohio, July 1982, 5.

[4] Maurine Beasley, “The Women’s National Press Club: Case Study of Professional Aspirations,” Journalism History 15, no. 4 (Winter 1988), 112-121.

[5] Elizabeth Burt, “A Bid for Legitimacy: The Woman’s Press Club Movement, 1881-1900,” Journalism History 23, no. 2 (Summer 1997), 72-84.

[6] Helen M. Staunton, “Mary Hornaday Protests Bars to Newswomen,” Editor & Publisher, July 15, 1944.

[7] Kimberly Voss, Re-Evaluating Women’s Page Journalism in the Post-World War II Era (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018)