“Quar-interning”: choosing and managing a productive digital internship during COVID-19

01 September 2020 – Jade Ryerson and Katherine Crawford-Lackey

In the last few months, the COVID-19 pandemic has meant that the techniques public historians use to engage communities have become increasingly digital, as have the methods we use to communicate with each other. Because COVID-19 continues to spread in the United States, public history organizations should consider how to offer enriching remote internship opportunities that are mutually beneficial to all parties involved. Today, we offer our remote internship model at the National Park Service’s Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education (CROIE) in hopes that it might be beneficial to public history sites and historians.

Katherine’s Perspective: Managing a Digital Internship

The number of internship cancellations at parks and programs across the agency prompted the members of CROIE to discuss how to host a summer intern effectively, particularly with the onboarding process at a halt.[1] Based in Washington, D.C., CROIE is managed by archaeologist Dr. Barbara J. Little and is dedicated to Telling All Americans’ Stories. In keeping with this mission, the office plays a lead role in organizing the agency’s commemoration of the centennial of the 19th Amendment and recognizing women’s voting rights. We hoped to hire an intern to author digital content on women’s history. Fortunately for us, the National Coordinator for the 19th Amendment Centennial Commemoration, Dr. Megan Springate, and I had hosted a virtual intern for the 2019-2020 academic year and had a working model in place.[2] Jade Ryerson, then a junior enrolled in DePaul University’s history program, joined our office virtually from Chicago in September of 2019 as part of the Department of State’s Virtual Student Federal Service internship program.[3]

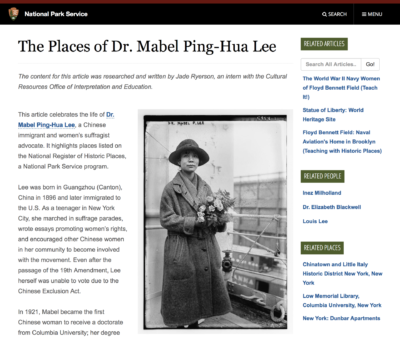

Working ten hours each week, Jade conducted research and wrote digital content on sites associated with women suffragists, including Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee, Zitkála-Šá, Nina Otero-Warren, and Mary Ann Shadd Cary. Her success identifying historic places connected to the women’s suffrage movement prompted CROIE to hire her as a paid National Council for Preservation Education (NCPE) intern to work remotely for the summer.

Effective and consistent communication and mutual respect, whether in-person or remote, has been essential to this internship’s success. Meeting scheduling varied depending on the time of year. During the academic year, we needed flexibility to accommodate Jade’s schedule. Jade and I checked in with each other every two weeks as there was leeway with project deadlines. But when Jade began the full-time NCPE internship this June, I knew I wanted to have a more structured routine that kept us both accountable and on track to complete the internship. I wanted to prompt myself to prioritize her projects and check in more regularly to ensure that I was providing enough support and guidance, while also giving Jade the space to use her creativity and research skills to identify compelling aspects of the 19th Amendment project. Throughout the internship, I’ve found it most successful when Jade played a role in shaping her experience by identifying specific projects within the broader topic of women’s history. Over the course of the internship, we’ve worked together to gauge the level of support needed on these tasks, allowing us both to make the most of the experience.

Jade’s Perspective: Choosing a Digital Internship

The end of my junior year and the onset of the pandemic brought new urgency to my questions about life after graduation. Internships lend themselves well to resolving this dilemma, so I was eager to join CROIE for the summer as a virtual intern. Because of my prior remote work experience with Katherine and Megan, I knew it was possible to make the best of a virtual situation and do professionally constructive and personally rewarding work.

Relying entirely on public digital collections to complete my work was challenging, but this provided me with a unique opportunity to gain hands-on experience as a researcher and interpreter working with limited resources. Considering sources available through the Library of Congress, Hathi Trust, and Internet Archive from the standpoint of both public and research access reinforced the importance of my public history work: to identify obscure content, amplify untold stories, and bring them to life.

To keep the internship constructive, it was essential to recognize each other’s time, labor, and changing circumstances (especially during the pandemic). A crucial benefit of the virtual internship was the flexibility to work when I could be most productive. Because of my classes and other jobs, I often worked on the internship first thing in the morning or long past what should have been my bedtime. Without access to the NPS web platform, my progress also meant additional work for Megan and Katherine because I could not build the webpages myself. By being realistic and transparent about our goals and constraints during check-ins, we were able to make the most of each other’s time.

By genuinely caring about my input and sharing my excitement about my projects, Katherine and Megan validated my work—which was especially valuable at this stage of my career exploration. I appreciated that they took the time to answer questions and offer advice about graduate school, careers, and even the prospectus for my senior thesis because those things didn’t directly apply to my work in the internship. Katherine and Megan also encouraged my professional development, suggesting everything from webinars on federal résumés to readings that supported my academic interests. Because of the pandemic, more training and educational programs were offered online, so I was able to participate in some unique opportunities even while living in a different city than my supervisors. Without ever stepping foot in the D.C. office, I still felt like part of the team and gained a sense of the workplace environment.

Closing Thoughts

“Quar-interning,” as we call it, offers mutual benefits. While working from home, virtual interns gain practical experience, evaluate career paths, add to portfolios, and forge professional relationships. Simultaneously, interns help institutions meet the growing demand for digital content to engage with a socially distant public and grapple with questions of authority and access.

We have yet to meet in person, but we’ve developed a close working relationship. Through trial and error since September 2019, we have learned that the hosting organization and the intern both need to be involved in creating this experience. Especially during this time of uncertainty, it is essential for public history institutions to support students’ professional growth through productive virtual internships.

~Jade Ryerson is an undergraduate majoring in history, with a concentration in public history, at DePaul University. She will graduate in June 2021 and will be applying to public history graduate programs this year.

~Dr. Katherine Crawford-Lackey is a graduate of Middle Tennessee State University’s public history program. Her research uses place-based methodologies to study American social movements and forms of public commemoration.

[1] Onboarding for new agency hires ordinarily requires a background check in order to receive non-visitor access to the office as well as a government-furnished laptop with access to internal systems and web authoring platforms.

[2] The National Park Service is commemorating the centennial of the 19th Amendment (August 2020) with in-person and digital programming provided by parks and programs service-wide. Dr. Megan E. Springate, CROIE’s Interpretation Coordinator, also serves as the National Coordinator for the NPS 19th Amendment Centennial Commemoration.

[3] Through the Virtual Student Federal Service, government agencies post virtual, unpaid internship opportunities to current college students who, in turn, contribute to projects that advance the work of government. Projects range from developing virtual programs and building apps to mapping economic inequality and analyzing data.