Repairing National Register nominations: technical matters

14 July 2020 – Heather Lynn Carpini

historic preservation, inclusion, working group, 2019 annual meeting, National Register of Historic Places

Authors’ Note: This is the first of three posts resulting from discussions of our 2019 NCPH annual meeting working group on improving existing National Register nominations. In this series, we’ll highlight best practices we developed—using our working group member case statements as a starting point—to encourage frequent revisions of National Register nominations. We consider these thoughts a starting point in figuring out how to think of National Register nominations as living documents that must change periodically to reflect the history of a given community and serve its evolving needs. Join the conversation in the comments!

The concept of “repairing” National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) nominations is multi-faceted and touches on a number of different issues that face practitioners, local governments, State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPOs), and the National Park Service alike. At the outset, it is essential that we acknowledge the technical challenges that go along with amending NRHP nominations. Through our working group discussion at the 2019 NCPH Annual Meeting in Hartford, we identified a number of different themes surrounding the “nuts and bolts” of repairing National Register nominations.

The first major hurdle is mindset. The National Register is the government’s “official list of historic buildings, districts, sites, structures, and objects worthy of preservation.” For many people, within the preservation field and in the general public, the completion of a National Register nomination is the “be all, end all” of the process. Once a nomination is accepted by the Keeper of the Register, the resource is officially recognized as historic by the federal government, and the ultimate goal of the nomination sponsor or the property owner is met: access to tax credits, protection during the Section 106 process, or an honorary designation has been obtained. The process is generally viewed as complete, and researchers move on to new projects. The nominations are not revisited until there is a need to do so for a pressing preservation or tax credit project. Accepted nominations often sit like an old history book or encyclopedia set, containing information that was considered accurate and sufficient at the time they were written, but which has often been eclipsed by new knowledge or documentation standards. Many preservationists view the National Register as the untouchable bastion of the field, and taking on amendments to old nominations seems impossible. Yet National Register nominations are not set in stone. They should be viewed as dynamic documents that can be updated or expanded over time as new themes and contexts are revealed through additional research, or as more recent historical events reach the 50-year threshold for nomination. Just as structures that are demolished or significantly altered can be de-listed from the National Register, so too can existing nominations be amended to include updated information, contexts, or events. Fostering this mindset within the preservation community is the first step in the repair of many National Register nominations.

Screen capture of the National Register of Historic Places website

How do we accomplish this mindset shift? One great suggestion that emerged from our discussion was that nominations acknowledge their gaps. For example, a nomination could note that it is not comprehensively exhaustive in its research, touch on additional avenues of research that may also reveal information on significant aspects of a resource, or honestly address the potential for a longer period of significance when documentation stops at the 50-year threshold out of necessity. Having these opportunities for additional research presented in the nomination may make the amendment process less daunting. This is an excellent option for new nominations, but how do we stretch this repair mindset to encompass older nominations as well? By offering workshops by the National Park Service or SHPO? In developing social media posts that highlight the successes of amendments? Through producing YouTube videos featuring properties that have had amended nominations, highlighting new information that has been brought to light? We have no consensus on a best practice, but we hope to open the conversation as to how this might look.

A second major hurdle to repairing National Register nominations is the lack of an established process for amendments. Different states and different regions handle these projects in their own way. The amendment process in New York may be very different from the preferred process in Florida, and both may be different from the process in Colorado. SHPOs generally address these types of projects on a case by case basis. An official guidance document for an amendment process issued by the National Park Service would help to streamline the process. Knowing how reviewers will view amendments and what information is necessary for different types of amendments would serve to make the process much less daunting to SHPOs, local governments, and consultants. There was general agreement in the group about the need for such a document, but we acknowledged the challenges of drafting and issuing this type of guidance.

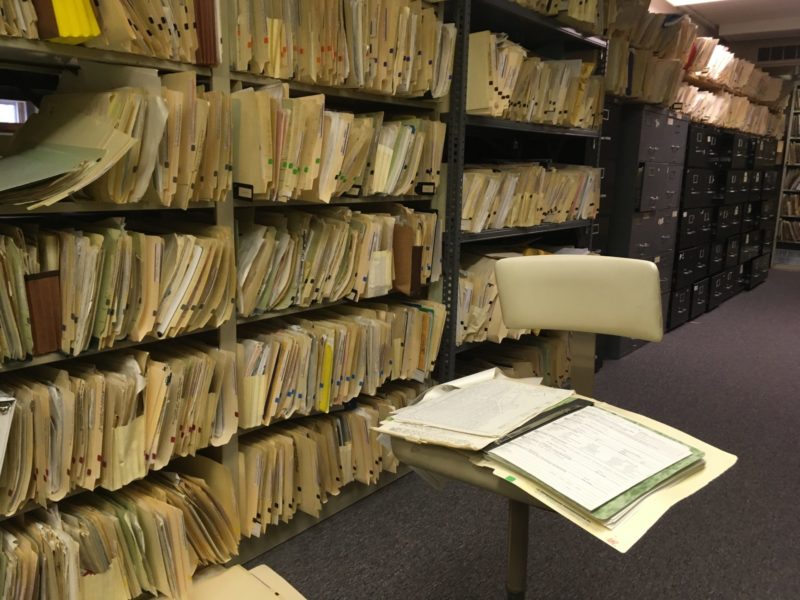

The New York State Historic Preservation Office’s National Register Files. Photo credit: NY SHPO

A third challenge surrounding the repair of National Register nominations through an amendment process goes deeper than the “how” associated with the process, and combines “how” with “who.” Modern National Register nominations are generally documents that include extensive research and writing on particular historic contexts and themes. Sufficiently researching and documenting a resource, even one that has already been nominated to the NRHP, can take a long time and time costs money. Updates to National Register nominations, especially large districts with very little information on contributing and non-contributing resources, can be labor intensive and expensive. Local governments or developers seeking tax credits for a project who need an updated nomination to fully document significant aspects of a resource may undertake amendments. But these types of updates are often done piecemeal and may not fully address all of the inadequacies of the nomination. How do we find the time and the people to update nominations? How do we identify which nominations need updating, when there are over 95,000 nominations that encompass more than 1.8 million resources throughout the United States? One idea is for SHPOs to have “wish lists” of their “problem nominations”—those that they know need updating but have no readily available sponsor. These lists would allow them to prioritize which nominations might get updated when resources become available. A related strategy is for SHPOs to suggest nomination updates as “creative mitigation” measures for certain Section 106 projects. For example, if updating a historic district nomination will benefit a community in a tangible way, by making tax credits and preservation resources available to more property owners, the update to a nomination may be a complementary option to more traditional mitigation measures. Finally, it would be beneficial for SHPOs to provide guidance to communities with older, out-of-date district nominations and sponsors of new nominations alike about the importance of updating nominations and suggesting a potential timetable for amendments.

Shifting our mindset and acknowledging that nominations can and should be updated is the critical first step. By taking a collaborative, open look at the current system and working with NPS and SHPOs to request clear guidance on amendments, we believe the National Register can continue to serve as a meaningful resource into the future.

~Heather Carpini is a Senior Historian/Architectural Historian at S&ME Inc.