Science and disability Q&A: Part 2

12 September 2019 – Nicole Belolan and Jessica Martucci

“How do you imagine the universe?” exhibition detail. Photo credit: Jessica Martucci (used with permission from the Science History Institute)

Editor’s note: this is the second in a two-part series based on a conversation between our Digital Media Editor, Nicole Belolan, and Jessica Martucci, a researcher at the Science History Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

NB: How do you think this project defines or redefines disability, and who does the defining?

JM: Disability is primarily defined in our project by the participants themselves. My interest has been to capture as much diversity of experience and perspective as possible. This means we have included stories from people who have sensory processing and learning disabilities, mental health diagnoses, physical disabilities, as well as stories from people who are blind or low-vision, and those who identify as members of the Deaf community. Our project is ongoing and I continue to look for stories from individuals in STEM who experience intersectional identities, including disabled people of color and those who identify as LGBTQ.

I think the biggest question the Science and Disability Project has opened up as a result of this approach is this very question of “What is disability?” Because when you look comparatively at what scientists with disabilities do and what scientists without disabilities do, the line between disability and ability gets really fuzzy. One of the examples I return to time and time again has to do with scientific instruments. Most scientific instruments are basically designed to help scientists visualize data that they wouldn’t be able to see otherwise. So, when you talk to a blind scientist who is using 3D or audio methods to “read” data, how is what they are doing fundamentally different from what a sighted scientist does? I don’t claim to know the answer to this, but I am excited by the potential insights we can gain in the history of science and disability by asking these kinds of questions.

NB: Has your involvement in this project led to any changes in the way contemporary scientists remember their professional heritage or how they approach their work in contemporary life?

JM: People with disabilities in STEM have often felt marginalized and even invisible due to the pervasive discrimination and bias they have faced. Many of the people I have interviewed have expressed feeling a sense of validation and gratitude because we are doing this work. I’m so glad to see that this work has this personal value to them. I think for many of my interviewees, the oral history interview is often the first opportunity they’ve had to really sit and reflect on their contributions to their field and to the disability community more broadly.

NB: What have you learned about the practice of public history, particularly as it relates to diversity, equity, and inclusion, while you have been working on this project?

JM: I’ve been pleasantly surprised at how well-received this project has been in the wider public. I didn’t expect people to outright reject this work, but the extent to which it has been embraced has been really great to see. I think the Science History Institute is in a wonderful position to bring the humanities’ perspectives to bear on how the public understands and engages with science, and by doing this kind of work in diversity, equity, and inclusion, we’re highlighting the great value of telling a diverse and inclusive history about STEM. By doing this, I really believe we are helping to open up space for more and more people to see a place for themselves in STEM.

NB: Since you’re working on a disability history project, I am sure you’ve thought a lot about how to make your project physically and programmatically accessible to participants and the public. Do you have tips for our readers about introducing accessibility into their own public history work? Did you learn anything new about accessibility while working on this project?

JM: The mantra of the modern Disability Rights Movement is “Nothing about us, without us,” so, for starters, I wanted to make sure that as we collected these interviews, we did so in a way that was collaborative and respectful to our interviewees. To me, a big part of honoring the people who have participated in this work is to make sure that they and everyone they know can access these stories.

In the process, we’ve learned that there is no one-size-fits-all way of designing anything that will always work for everyone. To be inclusive requires imagining our audience as extremely diverse in terms of ability and designing multiple pathways for engagement into everything we do.

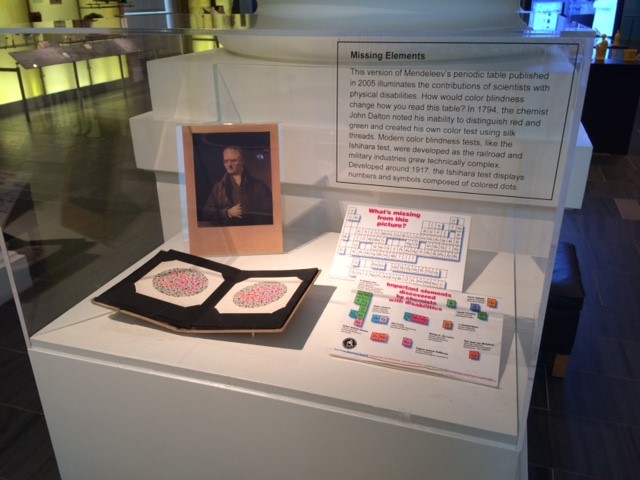

“Missing Elements” exhibition detail. Photo credit: Jessica Martucci (used with permission from the Science History Institute)

In terms of public programming, for example, our series this summer has given us the chance to try out more inclusive approaches like standardizing our use of live closed-captioning during presentations, hiring ASL interpreters, offering assistive listening devices, and designing activities that allow people to feel engaged, welcome, and included across a wide range of ability experiences. As far as our museum is concerned, the Science & Disability ExhibitLab represents our interests in bringing multiple sensory experiences into our exhibits. Our current ExhibitLab includes a Braille periodic table and accompanying text and we also display a raised-line anatomical image that guests can feel. These have been small steps, but they’ve also been relatively simple to incorporate. I’m excited to think about ways we can make all of our content more accessible.

Jessica Martucci earned her PhD in the history & sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania in 2011 and is the author of Back to the Breast: Natural Motherhood and Breastfeeding in America (University of Chicago Press, 2015). Her work on the Science History Institute’s Science & Disability Project is part of her broader interest in understanding the mechanisms and effects of exclusion and inclusion in the history of science and medicine.