Managing social media, doing public history

05 December 2019 – Max Farley and Krista Pollett and Brian Whetstone

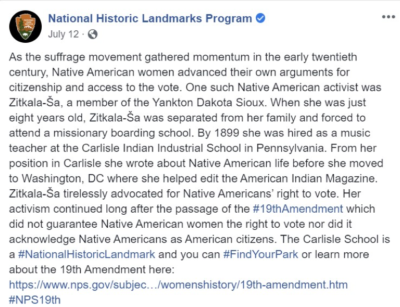

This summer, a team of National Council on Preservation Education (NCPE) interns oversaw the National Historic Landmarks Program’s social media accounts and explored firsthand how the creative chaos of shared social media management can be harnessed as a productive outlet for engagement and interpretation. One of our posts on the 19th amendment and Native American activism illustrates this phenomenon.

The Nineteenth Amendment, remembered as the constitutional amendment that finally granted women the right to vote, did not extend to Native American women. Native American women nevertheless fought tirelessly for the vote throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Zitkala-Ša, a member of the Yankton Dakota Sioux, was one such Native American woman. After being separated from her family and forced to attend a boarding school, Zitkala-Ša moved to Washington, D.C. and served as editor of the American Indian Magazine. From her position on the magazine’s editorial board, Zitkala-Ša advocated for Native American women’s right to vote long after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. Her efforts contributed to the passage of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act that formally established Native Americans as citizens.

On July 12, 2019, as part of a social media campaign interpreting the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, the National Historic Landmarks Program’s Facebook page highlighted Zitkala-Ša’s story. The post checked a number of boxes for the National Park Service and the NHLP: it featured a National Historic Landmark (the Carlisle School), promoted an ongoing NPS commemorative theme (ratification), and drove engagement and traffic by including a link to the NPS Nineteenth Amendment subject website.

Zitkala-Ša in 1898. Photo credit: Gertrude Kasebier, Smithsonian Institution, ID Number PG.69.236.108, https://www.si.edu/object/nmah_1006130

Screenshot by Brian Whetstone

Beyond meeting these objectives, however, something exciting happened: the NHLP Facebook post quickly took on a public-historical life of its own. This is just one example of the many stories that a team of National Council on Preservation Education (NCPE) interns shared during the summer of 2019 as we managed Facebook and Instagram pages for the National Historic Landmarks Program and worked with the National Park Service’s Cultural Resources staff. A national organization that coordinates preservation education efforts with public and private agencies, including the National Park Service, NCPE facilitated our internships with the NPS. Our decentralized group of graduate student interns operated out of NPS regional offices in Omaha, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. We promoted National Historic Landmarks located throughout US states and territories, and we ran focused social media campaigns on topics like LGBTQ history, Latino Conservation Week, and Telling All Americans Stories. We also utilized historical interpretation to tie National Historic Landmark (NHL) stories to larger themes, and we monitored our platform’s built-in analytics to improve the NHLP’s ability to capitalize on social media. As we coordinated posting schedules and dealt with day-to-day social media issues, we learned that the creative chaos of shared social media management can be harnessed as a productive outlet for engagement and interpretation.

Our team devised two methods to package and share National Historic Landmark digital content: themed campaigns and post scheduling. Themed campaigns encompassed efforts to highlight NHLP’s exemplary list of various historical and contemporary themes outlined by the NPS. These themes ranged both in their content and length from week-long campaigns such as Latino Conservation Week to the celebration of LGBTQ history during Pride Month in June to ongoing efforts like the centennial of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Complementing these these thematic campaigns were a series of “On This Date” (or #OTD) posts, which marked various anniversaries of historic events, such as state ratifications of the Nineteenth Amendment or the designation anniversaries of NHLs themselves. Our team also scheduled posts, drafting and queuing content for publication days or weeks ahead, which allowed us to proofread, edit, publish, and largely avoid daily content-creation deadlines.

Regardless of content, each post required a delicate juggling act between our national team that straddled multiple offices, time zones, and social media platforms. Through this sometimes chaotic relationship, we maintained an average output of one post per day. For public historians, efforts to synergize schedules should be familiar, but working across the same platform entailed more thoughtful engagement not only with our posting schedule, but with the packaging and output of each other’s content. This required our posts to be sympathetic to one another in tone, content, and frequency while working together as an interrelated and coherent whole. At times the desire to highlight “everything” punctured this otherwise unified front, such as when a post about the fiftieth anniversary of the 1969 moon landing occurred amid posts about Latino Conservation Week. Overall, our concerted efforts to reach across our decentralized positions in NPS regional offices shaped the NHL Facebook and Instagram pages into sharper, more engaging, and more coherent social media platforms.

Out of our team’s efforts to craft a coherent voice for our platforms emerged an overarching goal for our posts that emphasized connecting our audiences to each landmark’s unique history and the multitude of NPS digital initiatives. Foremost among our posts was the promotion of NHLs and the diverse connections to American history that they represented. Our secondary goal was promoting NPS resources like digital articles, park sites, theme studies, and web content generated by the NPS to our audiences. We also aligned our posts with the NPS’s service-wide messaging. While we fulfilled NPS imperatives,our team’s social media strategies curated posts that blended public history promotion and creation.

Our opening story reveals this process at work. As mentioned above, the post fulfilled NPS and NHLP outreach and education objectives. Beyond simple promotion, however, the post represents digitally-engaged public history as reflected in the post’s comments. Respondents expressed discomfort at what they called the “sins of our past” and noted that such “relevant facts” were ”never taught” in their own primary and secondary education. Zitkala-Ša’s story ignited dialogue over the fraught history of Native American assimilation, boarding schools, the U.S. Constitution, and citizenship rights.

For public historians, social media offers tremendous promise. However, social media invariably reflects the limitations of sharing authority on these platforms. Individuals could attach their own commentary and sustain a dialogue, but, in the end, the NPS maintains final authorship over the posts themselves. Likewise, decentralized social media management involves significant challenges that make such work difficult to streamline. Putting aside any attempt at navigating the ever-changing algorithms of Facebook and Instagram, decentralized social media management requires dedicated time and resources to make it worthwhile. Our team invested time and resources to search for eye-catching pictures and craft excellent posts, only for some to flop. The process of engagement played out on a sliding scale over the course of the summer. Sometimes our posts garnered only a handful of reactions, and at other times, they prompted robust conversation among our audience. We also faced a problem encountered universally by interns and public historians: how do you maintain and sustain project momentum? Faced with a concrete end date for our 10-week internships, we worked to inform our advisors of how best to proceed and maintain consistency.

Managing the National Historic Landmark Program’s social media identity let our team explore how public history operates in the digital world. We learned that careful, intentional cultivation of a social media platform and diverse content is a meaningful avenue for public-historical engagement. In the same breath, we wish to stress the importance of training and supporting social media content creators and managers to fulfill engagement and outreach goals within historical organizations. Due to the time and labor that goes into creating and managing content, truly successful social media strategies and campaigns are achieved when it is part of an employee’s main job duties, not an afterthought. Historical organizations of any size and resource capabilities can benefit by creating ongoing social media project plans and digital content strategies to accommodate and support the field’s growing need for social media expertise.

From our own experience, public historians hoping to employ social media should not shy away from so-called “difficult” history. As we discovered with the case of Zitkala-Ša, our audience most robustly engaged with stories and material that fell outside of nationalistic or patriotic narratives typically associated with sites of “national” heritage. But even material not considered “difficult” received engagement, seemingly without rhyme or reason. The scattershot responses from our social media audiences demonstrate to public historians that no story or history can or should be overlooked. And, like our experience sharing the story of Zitkala-Ša, social media maintains the power to bring nuance and dignity to complicated historical events. Ultimately, social media can provide something for everyone. It is, in fact, one of the greatest tools for the public historian.

~Max Farley is an MA student in the Public History program at Middle Tennessee State University. Max’s current research interests center on heritage tourism, National Heritage Areas, and histories of the American South. Max also works closely with the MTSU Center for Historic Preservation and MTSU Digital History.

~Krista Pollett is currently an NCPE intern in the Park History Program at the National Park Service headquarters in Washington, D.C. Krista’s current projects center on preparing oral history materials for the archive and conducting research and creating online content on women who championed preservation and conservation in the NPS. With the completion of her thesis on commemorative trends in the late twentieth century, Krista will earn her MA in public history from Texas State University this December.

~Brian Whetstone is a PhD student studying public history and historic preservation at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Brian’s research focuses on the history of historic preservation, particularly its intersections with the policing of mobility and managing urban change in the mid-twentieth century. Brian also serves on the National Council on Public History’s New Professional and Graduate Student Committee.