Spirit of the season

24 October 2016 – Alena Pirok

Promotional photo for Stratford Hall’s “Stratford After Dark” event. Photo credit: Stratford Hall Facebook Page.

It is Halloween time and ghosts are once again a topic of discussion. Last October works like Tiya Miles’s book Tales from the Haunted South and Sarah Handly-Cousins’s post on “Nursing Clio” argued that popular ghost tours depend on stories that demonize those who suffer. Their critiques were spot on, but they don’t apply to all ghost stories. The relationship between ghosts and history is much older than contemporary tours, and in most cases, these old tales lack the spooky or violent quality that characterize today’s hauntings. In fact, ghost stories in Virginia helped define homes and sites as historical and deserving of preservation.

My research into this topic deals solely with Virginia. This is because the state and its people have blurred the divide between the state’s history and its ghostlore. While other states certainly have ghostlore and stories that are informed by history, Virginians used their ghost stories to assert their state’s past. A journalist for the Richmond Dispatch once wrote, “Virginia people can tell more ghost stories than those of any other state.” Every neighborhood, the author argued, “has its story of the supernatural, its haunted houses, its lonely road, where strange sights and sounds have frightened the nocturnal wayfarer.” Unsurprisingly, many of the old colonial homes in Virginia carry ghost stories that complement their historical narratives. In recent years major sites like Colonial Williamsburg and Mount Vernon have posted ghost stories on their respective blogs. While historic sites have tried to tap into the more historical and less spooky side of haunting, tour companies have made good money offering customers eerie visions of popular downtown areas.[1]

Photo of the Wythe House that was in included in Marguerite DuPont Lee, “Virginia Ghosts,” (Richmond: William Byrd Press, 1930), 23.

The impulse to feature historical ghost stories is not a new trend; these tranquil specters are staples of Virginia’s place-based historical narratives. When researchers traveled throughout the state looking to catalogue old homes in the 1910s and again as a part of the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s, they considered ghost stories as part of homes’ significance. As author Robert Lancaster wrote in 1915, “no old Virginia mansion is quite complete without a ghost.” He explained that the Wythe House in Williamsburg boasted “no less than three ghosts.” The phantoms were the home’s owner George Wythe, as well as George Washington, who stayed in the house, and Lady Skipwith who dramatically flung herself off the home’s staircase in a fit of jealousy. Each spirit brought a bit of legitimacy; George Wythe’s ghost affirmed that he loved his home so deeply death could not stop him from visiting it. Washington’s ghost reminded people that the home was witness to important people and events, while Lady Skipwith’s ghost offered evidence of the exciting and dramatic social world of elite eighteenth-century Virginians. [2]

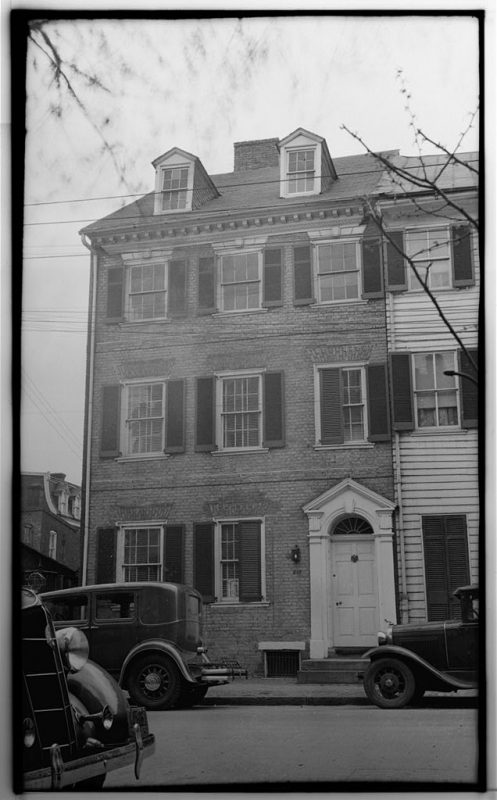

Colonel Michael Swope House, 210 Prince Street, Alexandria, Virginia. Documentation compiled after 1933. Photo credit: Historic American Buildings Survey (Library of Congress).

In 1938, Virginia Daingerfield was one of many WPA writers to submit the details of a haunting as historical evidence for the Virginia Historical Inventory project. Like Lancaster, she saw hauntings as significant. She profiled 210 Prince Street in Alexandria, the home Colonel Michael Swope, built in 1756. The homeowners and visitors claimed the apparition of an executed American spy roamed the garden and attic. [3] Daingerfield noted that many visitors claimed to see “the uneasy spirit” and found him to be a “dashing tragic figure.” The haunting, she said, made 210 “the most admired house” on a street lined with old colonial homes.

As with most historical specters, the one at 210 Prince Street was not scary and did not seek vengeance; rather it asserted the home’s age and significance. While most of the buildings on Prince Street were constructed in the eighteenth century, survived the Revolution and Civil War, and lasted into the twentieth century, only 210 could claim a special connection to the past through the spirit of a martyred patriot. [4]

These haunts were not exclusive to homes, or buildings for that matter. Ghostlore worked well to define and explain the significance of otherwise unremarkable sites. Take, for instance, the “Haunted Woods.” Virginia ghost story author Marguerite DuPont Lee included the tale of the “Haunted Woods” among her entries of haunted homes, because like the stories attached to houses, the wood’s tale recalled historical narratives.

She reported that as far back as 1798, residents spoke about ghosts in and around the woods. DuPont Lee stressed that the woods were “reputed” both “far and near” as notably haunted. The wood’s spooky nature came from people’s habits of hiding out and burying things under the cover of the dense pine forest. The people DuPont Lee spoke with said that among the runaways and treasure chests the woods harbored ghostly skeletons, armor clad soldiers, “two officers and four men” from Cornwallis’s army, “murdered royalists,” and from time to time, a flying pirate ship. While the list may seem exaggerated, DuPont Lee assured readers that it was historically accurate. She explained that pirates were known to hide out in the bay. Further, Sir William Berkeley, Philip Ludwell, Lord Dunmore, and others sought escape by crossing through the woods to waiting ships during times of upheaval. The diverse group of haunts illustrated locals’ sense that their occupation of the area was in context with multiple narratives, events, and people who made the woods remarkable. [5]

These kinds of stories fell out of favor after World War II, when historical sites began to hire professionally trained workers rather than rely on volunteers and local traditions. Today ghostlore is making a return to historical areas and homes across the United States. As Miles, Handly-Cousins, and others have rightly pointed out, the old stories that these events are built on can promote cultures of oppression and impede critical thinking. However, if we look at these stories critically and actively fight against ignorant narratives, we can free ghostlore from its macabre prison. These stories are unique approaches to historical experience and illustrate an under-acknowledged sense of place. This Halloween I encourage you to seek out a ghost tour, or a historic site’s haunted event and ask yourself: What is this telling me about the past? What does a haunting add to this place? You’ll find that the best stories change the way you understand place, and speak more about things that can be explained than the things that cannot.

~ Alena Pirok is a doctoral candidate in the department of history at the University of South Florida. She studies public history, museum history, and tourism history. Her dissertation “The Common Uncanny: Ghostlore and The Creation of Virginia History” looks at the relationship between historical sites and ghostlore.

[1] “Virginia Ghosts” Richmond Dispatch, December 9, 1900; Ivor Noel Hume, “Doctor Goodwin’s Ghosts: A Tale of Midnight and Wythe House Mysteries,” CW Journal (Spring 2001); Adam D. Shprintzen, “Great George’s Ghost: Josiah Quincy III and His Fright Night at Mount Vernon,” George Washington: The Man and Myth, Mount Vernon website.

[2] Robert Lancaster, Historical Virginia Homes and Churches (New York: Lippincott Company, 1915), 20.

[3] Virginia Daingerfield, “Garland Lambert House,” March 28, 1938. Computer File. Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[4] Daingerfield, “Garland Lambert House.”

[5] Marguerite DuPont Lee, Virginia Ghosts (Richmond: William Byrd Press, 1930), 38-43.

We are proud of our “ghostly” interpretations here at Stratford Hall…..and thank you for featuring our house in your article….

Jon Bachman

Public Events Manager

Stratford Hall

483 Great House Road, Stratford, VA 22558

Phone: (804) 493-1972 | Fax: (804) 493-0333

http://www.stratfordhall.org

http://www.innatstratfordhall.org

While she doesn’t write about any real locations (not by name, at least), Virginian Ellen Glasgow offers interesting insight into Virginia culture in her book, The Shadowy Third and Other Stories, first published in 1923.