Finding their voices: the Williamsburg Bray School scholars’ legacy

25 April 2025 – Michael Caraballo

This article is the author’s personal opinion and does not necessarily reflect the views of Colonial Williamsburg.

In February 2023, I began working at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (CWF). At the same time, an original structure then known as the Williamsburg Bray School was being moved from the College of William & Mary onto the museum property at the corner of Nassau and Francis Streets. The Bray School, a school that taught free and enslaved Black children the ideals of the Anglican faith, became the eighty-ninth original structure in CWF’s Historic Area.

Bray-Diggs building sitting in front of its new foundation, February 2023. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

For years, the descendants of Williamsburg’s enslaved population have recalled stories of their ancestors attending the Bray School and a Baptist church in the city. Many people believed that the school was demolished and the descendants already knew what happened to their church: CWF purchased the property and demolished the nineteenth-century structure to make a parking lot in the 1950s. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation made efforts to interpret the Bray School and the institution of slavery to varying degrees of success, including having the museum’s audience watch a reenactment of enslaved people being sold. However, when the Bray School was rediscovered, it forced the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation to face the history of slavery head-on and confront its own institutional neglect interpreting the subject matter.

Open for almost 100 years, CWF has been at the center of localized segregation and discrimination efforts. Relatively recent changes to the museum’s programming tried to make up for this lack of interpretation. The African American history program was formed in 1979. It eventually grew into its own department (which was later dissolved by 1996) and this department interpreted enslaved plantation life on the Carter’s Grove property, which the Foundation sold by 2007. CWF often interprets slavery in a cyclical motion: it interprets slavery until it receives negative feedback, dissolves a program or department hoping that will realign its nonpartisan agenda, and establishes new management who tries a similar approach in interpreting African American history.

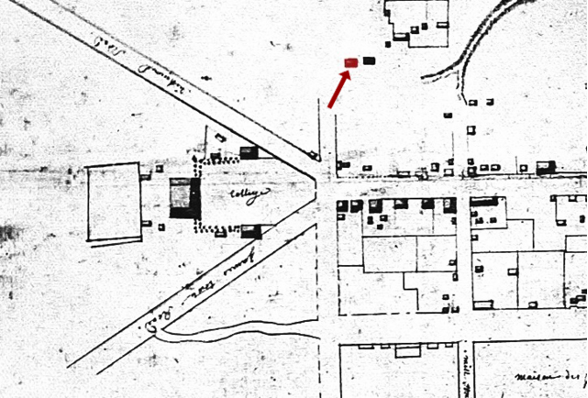

Bray-Diggs House located on the Frenchman’s Map (1782). Image credit: Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-4.0

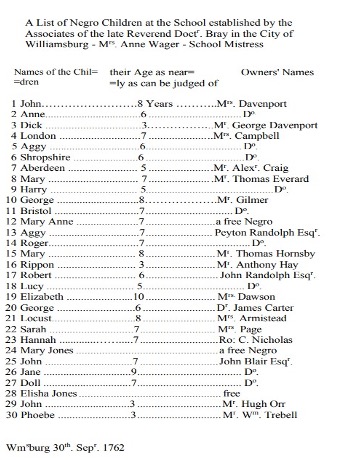

The Bray School allows the Foundation to reintroduce a history that is often clouded in mystery: the paradox of religious inculcation and the opportunities that arise with education of Black children. The school was open for fourteen years from 1760 until 1774 and taught upwards of 400 enslaved and free Black children reading, spelling, punctuation, and needlework (for the girls). Historians know of 86 children’s names from three surviving student lists still in existence (from the years 1762, 1765, and 1769).

Transcribed Williamsburg Bray School student list of 1762. Image credit: William & Mary Bray School Lab.

CWF formed a committee on how to interpret the site before it opened to the public in September 2024. This marked 250 years after the school’s closing. Members from various departments, divisions, and the descendant community were all a part of this meeting. At the time of writing this article, the building’s restoration has yet to be completed and the committee is no longer active for financial reasons.

The committee agreed that my department, the Department of Historic Interpretation, was to be trained in dialogic interpretation. Otherwise known as the Arc of Dialogue, this form of interpretation asks guests to participate by leading a discourse welcoming every person’s background and preconceived notions on a subject. The interpreter provides a historical overview and guides guests through the dialogue with questions (divided into four phases, with each question encouraging a more personal response) to further the discourse. If the interpreter notices that guests are not willing to open up, then the interpreter will stay in phases one or two (superficial rather than personal). While the descendants were a part of the initial interpretive-planning committee that had since become inactive, no descendants were in the room upon training for the Bray School site, which instead focused on Arc of Dialogue interpretation. This move implicitly detaches the interpretation from any ethos meant to guide the interpretation in the first place.

Upon entering the site, most guests believe that teaching enslaved people was illegal–which was true for the nineteenth century. So, many guests come to the Bray School thinking its intentions were good. The interpreter’s role is to introduce the paradoxical nature of the school so visitors better understand the children’s experiences. Yes, enslaved and free Black children were afforded an education many people nowadays view as “traditional,” but they attended the school to read books and sermons supporting enslavement in order to save their souls. Yes, they were taught domestic skills, but only to better serve their enslavers and to increase their economic value. Juggling this dichotomy brings many incredible interactions, but the pitfalls are substantial. Guests often leave mid-interpretation or ask questions that pivot the dialogue when they get uncomfortable. Ultimately the story of the students gets muddled.

Interior of Bray School schoolroom with reproduced school benches and books. Photo credit: Michael Caraballo

As the nation continues to move farther apart on the political spectrum, even disagreeing on the necessity of teaching certain subjects in educational facilities, interpreters are left at a crossroads. If guests are leading a dialogue based on their responses but refusing to engage with the difficult portions of history, how does one justify the interpretive necessity of the site? While the Foundation prides itself as a center of political discourse, limiting the voice of the descendants and catering to dialogic interpretation that allows a largely white audience to maintain their comfort parallels the history of the Bray School in dramatic irony.

Interactions like these beg the question that the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation continues to struggle to answer: how can the Foundation interpret the institution of slavery, acknowledge the museum’s legacy of racial inequality, and also be a place where all history can be told holistically and unapologetically? As the College of William and Mary, Jefferson’s Monticello, and Madison’s Montpelier continue their work of descendant community engagement, time will tell if CWF finds a way to join their museum counterparts or continue its cyclical motion of interpreting the history of slavery only when the museum feels most comfortable.

~ Michael Caraballo is a public historian working for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation as a Lead Historic Interpreter. He received his MA in Public History at Liberty University and his research interests focus on race, religion, and gender in the United States prior to the Civil War.